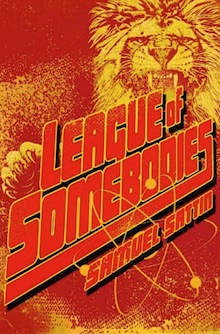

Our Research Notes series invites authors to describe their research for a recent book, with “research” defined as broadly as they like. This week, Samuel Sattin writes about “League of Somebodies“http://www.indiebound.org/book/9780985035501, out now from Dark Coast Press.

+

THE UNAVOIDABLES

I remember after finishing the first draft of League of Somebodies (and by draft I mean the esoteric morass of language I’d learn to identify simply as BOOK for three years), I showed it to my mentor, and avowedLOS Godmother, Cristina Garcia, who’d been a champion of my writing since I first landed in her class as an MFA candidate.

I remember after finishing the first draft of League of Somebodies (and by draft I mean the esoteric morass of language I’d learn to identify simply as BOOK for three years), I showed it to my mentor, and avowedLOS Godmother, Cristina Garcia, who’d been a champion of my writing since I first landed in her class as an MFA candidate.

Cristina’s writing is of a different aesthetic strand than mine, but at the same time, it really isn’t at all. We share a lot when comes to our love for language, and our appreciation for outlandish forms of expression may not appeal easily to traditionalists. While I’m interested in science fiction tropes and her work is naturalistic, we’re both thrilled by dark character studies and books that move. By move, I mean what stuff takes you quickly from beginning to end while making you slow to the point of meditation in all the right places.

What I learned from Cristina principally, however, as she took a keen eye to my nescient student work, was the importance of specialized knowledge, the idea that you should convey the warp and woof of the universe you choose to churn in words with an unflinching devotion to detail. Her work is the stuff of extensive research, of studies ranging from bullfighting and tumultuous South American politics atmospheres to the manner in which Americans adopt children from Guatemala at specialized fairs. You can taste, smell, and feel Cristina’s world. I wanted others to say the same of my work. Who doesn’t want to be believed?

I think all good novels require some degree of research. The very principle of ‘setting’ lends itself to physicality. We’re fond, as humans, of establishing identification with our surroundings. When reading a piece of literature especially we feel angry or betrayed if the work in question is not ‘convincing’ enough. By convincing we mean believable — ie: Can you find your footing on the worldview being unraveled over 92,000 sum odd words?

A convincing narrative doesn’t necessarily stem from inhaling historic tomes (although doing so will lend most things you do grace and authority). But even if your novel takes place within an 8 × 8 glass cube, thought and sensation need to maintain physicality. My novel is based on a premise that is as absurd as premises come: a madman tries to make his son into a superhero by sneaking measured amounts of a poison plutonium based compound into his food. The result of this frivolity is 400 pages of family saga and false alarms where death is both certain and utterly nonexistent.

In the world of my main character, Lenard Sikophsky, rules had to be set for the sake of progress. The story begins in 1967 Boston, anyway, in a city I know but in a time before I was born. In order to understand what that meant I decided to study not only the events of the period, but the clothes, the food, the houses, the wildlife. I had to make sure that I knew how to maneuver League’s world. For if I couldn’t, how could anyone else expect to?

This feat called for a generous admixture of whimsy and structure. I didn’t want to be bound by research, stuck inside the rigors of time and space, reading more about jack wood pine then writing work itself (especially considering the surreal nature of the novel), but I also didn’t want time and space to be viewed as irrelevant either. I researched everything from lions and chest hair growth to Herbert Marcuse and Radithor. Although I already read comic books to a degree that would make most twelve-year-olds jealous, I took it to the next level, surrounding myself with everything I could find with panels and ink. With every year that passed in Lenard’s life, so did acts of historical, physical, and environmental significance. If a scene I wrote required the hero use a tube of superglue, I had to figure out if superglue was in fact a commodity in 1967. The same went for televisions, cars, landmarks, and sports’ rosters. Any event referenced whose place in history may have undermined the authority of my character’s unique worldview I had to check on with ruthless consistency. Research, then, was never done in bulk, as in combing through thousands of pages before sitting down at the computer and interspersing facts from my feeble human data-stores. It was a constant process. A daily pursuit. Writing was research, and research was writing. The story changed as the facts poured in. I began to feel you could view a novel as a Mobius strip, striking polyps of tangential information from the surface in order to increase flow and continuity. In the end, it was the pace that mattered. The novel had to narrative scaffolding had to be bolstered by fact, but not to a point of unsightliness.

Research is writing, in my opinion. I don’t think the pursuit is escapable for a novelist. If you want to depict any reality, whether it’s of this planet or one made of mercury gas and magma, then you have to be on your toes when constructing its basic building blocks. If you don’t, the reader will call bullshit, and you’ll end up being flayed for disingenuousness by those who might have been rallied to your side.

+++