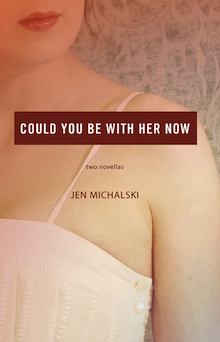

Our Research Notes series invites authors to describe their research for a recent book, with “research” defined as broadly as they like. This week, Jen Michalski writes about Could You Be With Her Now (Dzanc Books).

+

The two novellas in Could You Be With Her Now are like water and vinegar. One (“I Can Make It to California Before It’s Time for Dinner”) is the first-person point of view of a mentally challenged 14-year-old boy who accidentally kills someone. The other (“May-September”) is about a romance between a young woman and a much older widow. But, like all stories, they share common elements, like love and loss, risk and regret, and they germinated in somewhat-similar ways. Of course, I realize now I’ve finished writing this note, that it would have been easier to talk about my forthcoming novel, The Tide King (Black Lawrence Press, May 2013), which is filled with all sorts of stuff I knew nothing about before I wrote it (World War II, wild herbs, partition-era Poland, country music, and smoke jumpers). But I think the emotional landscape that the writer winds up mining—in imagery, half-remembered dreams and daydreams, the unexplainable collision of plot with the emotional beat of the narrative—is equally important, albeit not always as eloquent. In those gauzy spaces, the two novellas in this collection were formed.

The two novellas in Could You Be With Her Now are like water and vinegar. One (“I Can Make It to California Before It’s Time for Dinner”) is the first-person point of view of a mentally challenged 14-year-old boy who accidentally kills someone. The other (“May-September”) is about a romance between a young woman and a much older widow. But, like all stories, they share common elements, like love and loss, risk and regret, and they germinated in somewhat-similar ways. Of course, I realize now I’ve finished writing this note, that it would have been easier to talk about my forthcoming novel, The Tide King (Black Lawrence Press, May 2013), which is filled with all sorts of stuff I knew nothing about before I wrote it (World War II, wild herbs, partition-era Poland, country music, and smoke jumpers). But I think the emotional landscape that the writer winds up mining—in imagery, half-remembered dreams and daydreams, the unexplainable collision of plot with the emotional beat of the narrative—is equally important, albeit not always as eloquent. In those gauzy spaces, the two novellas in this collection were formed.

Of the two novellas in Could You Be With Her Now, “May-September,” came to me as fully-formed in a dream. This happens a lot. Some people think I’m cheating because I’m doing the hard stuff while I’m asleep, but I think all great work happens when consciousness is dimmed and the subconscious is allowed to poke out its furry head. Just like Danny Torrence has the shining and Keanu Reeves has the matrix, writers have this “shining” of the possible, the ability to see the grid of all the possibilities of a life or situation, living or dead, past or future. And we jigger with those potentials constantly, daydreaming or asleep, because it’s in our DNA to do so. Often I feel like I’m half in this world, half in some other unrealized potential one. Some people—one’s family and significant others, perhaps—would call this absent-mindedness, but we’re actually doing really important work when we’re staring slack-jawed into space instead of doing the dishes and I’m glad I have the opportunity here to set everyone straight.

So, yeah, “May-September”—it was first a beautiful, sad dream about a much older woman, Sandra, who is in the twilight of her life, and Alice, a woman in her twenties, who is helping Sandra with her memoirs. It seemed fitting that Alice is a young writer and that Sandra is someone trying to find the point of her own story. They do not have much in common except this strange, purgatorial space they are sharing for the time of the project. In the novella this place is Sandra’s condominium, but spiritually it’s where Alice is recovering from a breakup and the death of her father and Sandra is struggling with immortality and meaning in her life. Anyway, in this rarified space they’re able to find real affection and love for each other, a relationship that can’t survive once the space is pricked and the contagions of the world filter in—Alice’s ex, Sandra’s daughter, Sandra’s health, Alice’s burgeoning career. I wanted to write about not only one of the seemingly last taboos in our society, same-sex, May-December relationships, but also those special situations in which people heart’s beat at the same pulse and they achieve complete synchronicity before they spiral away in different directions, back to their own beats.

The most important research in “May-September” involved the type of music that Sandra, as a recreational pianist, would play. She loves Beethoven and Barber and Grieg. There was also the construction of her life in flashbacks—her husband Jack, her friend and brief lover Georgi, her lover Leroy—how people spoke in the fifties and sixties, the types of appliances and cars and drinks they’d be having. Although a time suck, I love this part the best: there’s a certain excitement about going onto Google and looking at old Chevys and Maytag appliances and listening to Dionne Warwick and Eartha Kitt and wondering what other sort possible tangents you are going to imagine from there.

The most difficult and important process of “May-September” was its voice, its lyricism. Whereas the source dream was beautiful and bittersweet imagery, I wasn’t sure what that all sounded like on paper. It wasn’t until I began feel the cadence of the sentences in my head a week after the dream that I was able to begin writing, and then I just sort of put the words in the blanks, my feet in the footprints already there. The image of Danny Torrence in The Shining walking backward his own footsteps in the snow maze seems particularly poignant here.

“I Can Make It to California Before It’s Time for Dinner,” the other novella in the book, did not come to me from a dream, although I am ashamed to say I cannot remember from where the idea came at all. It grew from a short story I’d published in Avatar Review, but I can’t remember why the short story. However, the writing part of writing is a lot like the dreaming part of writing; you’re in this sort of trance, and you don’t why exactly where inside you’ve conjured the idea but look, there it is, on the page. At best guess, I was profoundly affected in the seventh grade by my reading of Flowers for Algernon, which is told in the first-person point of view of a mentally challenged janitor, Charlie, and I’m equally fascinated by voice and lyricism in writing. I think I’d also met Michael Kimball around that time and bought into his belief of discovering one’s own language, of knowing which words and sounds you and your characters would use or never use, what the emotional cadence of a piece is. It was difficult for me to channel the voice and mindset of someone with a compromised reality like Charlie, but once I got there, it just sort of all spilled out, fully formed, like Athena from Zeus. It’s funny, because even though both of these novellas are very lyrically driven, they couldn’t be more different in terms of sounds and subject matter.

So in “California,” a 14-year-old developmentally disabled boy, Jimmy, accidentally kills a neighborhood girl he was a crush on and runs away, hitching a ride with a trucker who is not as trustworthy as Jimmy thinks he is. The most important part of the research was the truck. I looked at a lot of tricked-out rigs on the Internet because I needed to understand the layout of the cab (where Jimmy is unwittingly held prisoner). I do remember where the big-rig and trucker (Big Ed) part of “California” came from. Driving home from Pittsburgh after a reading at the New Yinzer series a few years ago, I remember being fascinated by the all rest stops along the way—there’s a huge one about an hour east of Pittsburgh with the biggest Pittsburgh Steelers store (yuck) I’ve ever seen. Life on the road has always intrigued me—I’ve already written a short story set at a Big Boy restaurant in a Delaware travel plaza. And I’ve daydreamed at least once about being a trucker (even though I’m a terrible driver of cars and I even broke my arm riding my bicycle). The road is a symbolic purgatory for me, a place from here to there, from this to that, a process and never a beginning or ending. And all stories are really that journey; I’m just glad I get to ride shotgun.

+++