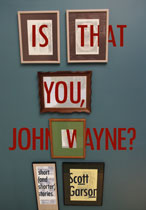

Our Research Notes series invites authors to describe their research for a recent book, with “research” defined as broadly as they like. This week, Scott Garson writes about Is That You, John Wayne?, out April 30 from Queen’s Ferry Press.

+

It could probably be pointed out that in most things, if I bother to have a philosophy, then it’s one that serves to justify the saving of trouble or time. I have no philosophy of fiction writing. One reason: the saving of trouble and time in fiction writing is, at best, beside the point. But with research related to fiction writing? Here I have thoughts. A writer could go with that iceberg thing. What is it, nine tenths underwater? Seven eighths? A writer could go with that, further supposing that for the huge concealed part of a story’s information — available to the writer and providing basis for the words but not written — lots of research must be done. But research takes time and is trouble. And so my philosophy: research sucks.

It could probably be pointed out that in most things, if I bother to have a philosophy, then it’s one that serves to justify the saving of trouble or time. I have no philosophy of fiction writing. One reason: the saving of trouble and time in fiction writing is, at best, beside the point. But with research related to fiction writing? Here I have thoughts. A writer could go with that iceberg thing. What is it, nine tenths underwater? Seven eighths? A writer could go with that, further supposing that for the huge concealed part of a story’s information — available to the writer and providing basis for the words but not written — lots of research must be done. But research takes time and is trouble. And so my philosophy: research sucks.

Before I get into the metaphysics of this view, I need to make a distinction between what I’m going to call Micro- and Macro-level research (hoping this doesn’t sound too professorial). If a writer does any realism — I mean if the writer is interested in getting readers to accept her fictional world as the one we think we share — then all sorts of factual questions are going to come up during the course of the work. Can we call this Micro and leave it at that? (See Roy Kesey’s essay in this space for a really excellent take). The other kind, Macro, would be research that is more in keeping with the iceberg metaphor: a body of research, supporting the story, inseparable from the story’s conception. And that’s what I say sucks (if you’re trying to keep track).

Richard Bausch used to talk about rooms, like in houses. I can’t quote him, but the basic idea: as a writer, you will occasionally have to put your characters in rooms, and you have two choices there: go out into the field, find a good room and take notes, or just make the room up. Just imagining the room seemed easier to me. I was inclined to go that way. But the point, for Bausch, had nothing to do with efficiency. If you research the room, he argued, then you will know all these little things about it. Like does it have curtains. What material. What design. You might like all these little things you now know about your room, and you might therefore want to put them in your story, whether or not your story really calls for them.

Richard Bausch is not on record as saying “Research sucks,” but moving on, I will be assuming his full support for my position.

Not long ago I read a book that a friend recommended, a historical spy thriller by a writer who works, according to his publisher, in the tradition of Graham Greene. Tons of research had gone into this book, clearly. And the writer was skilled. He didn’t just dump the research into his pages; he used it to create a full and sensuous map of the streets of Occupied Paris. So what’s the problem? That comparison. Graham Greene. You could call a novel like Greene’s The Quiet American a spy thriller, and it’s certainly rich in period detail, but there’s a reason that none of that comes immediately to mind when you think about the book. The Quiet American is about something. And the thing that it’s about is hard to name. Not Vietnam or the French-Indochina War. Not Communism or Democracy. It’s something that wraps in all of this, but it’s something else. Something further. And it’s what makes the The Quiet American a great book.

That other book, set in Occupied Paris, was about nothing but Occupied Paris. I could see no purpose for the other book — other than learning about Occupied Paris. (Maybe that’s what makes a book ‘historical’ for a reader: it depends on consensus History — the story of World War II, in this case; without History, it lacks meaning and shape).

Are we good? Are you seeing the way in which research can suck?

Behind my mistrust, there’s a value, of course. I’ll indulge myself by speaking to that:

I love stories. I’m a story junkie, and why I can’t stop: each story is its own perfect engine. Each is different, each made in a dream. Stories are of and for the world but don’t work in accordance with the world’s set rules. I can’t tell you the same thing in a story that I can tell you right now. I can’t reach you with the brain I’m using. Writing stories, I cross a border. Will there be any use to what’s there? It’s never sure. But in the end, from this side of the line, good stories retain their alt-glistening. They always seem a little scary. What they offer, in substance and mode, will be something very clearly not known.

Whenever I read stuff like I just wrote there, in that last paragraph, I think, man, this writer has really got it together. This writer is really solid, to be able to talk like that.

I won’t object if you want to form these kinds of conclusions about me. But I was speaking in the ideal, and as a writer and a person I usually fall short of the ideal. So let me close by discussing a part-failure.

Just about ten years ago — March of 2003 — was an interesting time to be alive in the United States of America. I remember having that conscious thought: this is an interesting time to be alive in the United States of America. I was living in Santa Cruz, a place I didn’t relate to, and we were going to war, and we were going on Spring Break, and we were enjoying March Madness, and I thought, wow, I have to write about this. I have to capture it, get it all down. So I researched in advance. I read and saved two or three weeks worth of A-sections of the San Jose Mercury News, and I watched TV and filled pages with notes. I thought, Here’s a story. I even told people about the story I would write, how good it was going to be.

You can see where this is going. There was no real story at all. I had nothing: just an issue; stuff for a creative perspective piece, like something you might read in Harper’s if you’re the kind of person who can stand to read a whole piece in Harper’s.

Still, I got lucky. In my collection, there’s a story called “In Lieu of My Final Paper.” It started as a dalliance, an amusement. I mean it lacked something. I can’t really say what it lacked, but I remember the excitement I felt when my daydreams on the story led me to take up that packet with all of my March ’03 notes and San Jose Mercury News A-sections. It was a fit. I didn’t know where the story would go then, but I could feel that it was going to be good.

Is that Macro-type research? Have I ended by saying that research doesn’t suck? Do I contradict myself? If so, how to finish this essay?

Is it all right if we just call it done?

+++