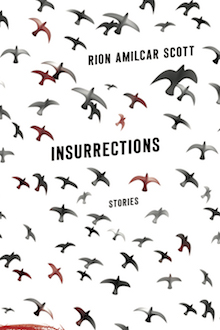

Our Research Notes series invites authors to describe their process for a recent book, with “research” defined as broadly as they like. This week, Rion Amilcar Scott writes about Insurrections from University Press of Kentucky.

+

Three Insurrections

It’s said that when an elder dies it’s as if a library has burned. When my grandmother passes at 101 I feel as if a whole city of libraries has become ash. When she was living, my father encouraged me to sit with my grandmother — his mother-in-law — and record her stories and then later shape them into something. That’s not what I do, Dad; I write fiction, I’d say. And with more imagination than I ever had, my father, the lawyer, would reply, So, you can use your grandmother’s stories in your fiction. I used to be a journalist and when that was done, I wanted to be far away from reporting and interviewing and all that, even if it could help save some books from a burning library.

It’s said that when an elder dies it’s as if a library has burned. When my grandmother passes at 101 I feel as if a whole city of libraries has become ash. When she was living, my father encouraged me to sit with my grandmother — his mother-in-law — and record her stories and then later shape them into something. That’s not what I do, Dad; I write fiction, I’d say. And with more imagination than I ever had, my father, the lawyer, would reply, So, you can use your grandmother’s stories in your fiction. I used to be a journalist and when that was done, I wanted to be far away from reporting and interviewing and all that, even if it could help save some books from a burning library.

+

In my parents’ basement there used to be this pipe. It had a sweet wooden smell and it also carried the scent of tobacco ash from the last time anyone smoked it, which was years and years and years before my birth. I played with it as a child and also as a teenager, sticking it in the corner of my mouth and miming mock sophistication. It was proof of my father’s past as a smoker, but also, little did I know, spoils from my father’s very brief career as a revolutionary, the spoils of black rage, a tiny relic of a historic moment.

+

Before I sit with my father to interview him, I take inventory of everything I need to know: I want to know about my father’s past. I want to know about the 1960s beyond the revolutionary fairytales I constructed in my head during my twenties. I want to know why he would emigrate in the 1960s from Trinidad & Tobago — a mostly black country — to a country where his blackness identified him as a danger, a threat, a lesser man. I’m a father now and trying to do at least as good a job as my own father had done so I want to hear about my grandfather, my dad’s model of fatherhood, a man who died many years before my birth and a man my father rarely speaks about. Most of all, I want to construct a story by shaping the raw material of someone else’s experiences rather than my own. I envision the story as something akin to James Joyce’s “The Dead.” It will end, I imagine, with my father standing in the law library at Howard University and seeing snow for the first time. I read “The Dead” over and over in the three years it takes me to write “Three Insurrections,”* the final story in my collection, Insurrections, but no such scene ever makes it to the page.

+

I read Selwyn Cudjoe’s Tacarigua: A Village in Trinidad several times, particularly the parts that mention my grandfather and grandmother, Vernon and Clotilda Scott, and the work they did in the community. I knew my grandmother, my father’s mother, and I miss her dearly. I linger over the picture of my grandfather in the book. He looks like my oldest uncle, Rawle. I post the picture on Facebook and Twitter.

+

I sit with my father for our first interview. We are at the dining room table where my grandmother used to sit with me and tell me stories of her youth. The first thing my father does stuns me. He details the plot of a novel he’s been writing in his head for years. The main character is based on his father and the story re-mixes all he knows of his father and imagines all he doesn’t know. When he finishes and his tale of an orphan and headmaster of a school (like my grandfather) comes to its tragic conclusion, my father says, You can use that if you want.

+

We have two more interviews. Each time we speak for an hour and I leave dazed, imagining the Trinidad of my father’s youth, the D.C. of his young adulthood. Between our discussions though, I read again and again one of my favorite books, V.S. Naipaul’s Miguel Street — a book set on a fictional street that would be somewhere near my mother’s neighborhood in Trinidad’s capital city, Port-of-Spain. I read Derek Walcott’s poetry. My father tells me in our interviews that he took a drama workshop taught by Walcott before he left the island. I imagine Walcott talking to my father and at the same time, in his head, constructing some of the poems that have moved me over the years. I read as much Caribbean literature as I can, everything I come across on my parents’ shelf and on mine. I set my Pandora app to play music similar to calypsonians, The Mighty Sparrow, Lord Kitchener and others. When the Caribbean Film Festival comes to town I take my parents to see a documentary on calypsonian, Black Stalin. One morning I rise to make a breakfast of fried bake (delicious! As good as my granny’s) and salt fish (a failed culinary experiment so dispiriting I am still thoroughly traumatized). I find clips on Youtube of Trinidadian comedian, Paul Keens Douglas, and I laugh and laugh. The voice of Neville Samson, the father in my story, I figure, would be somewhat dissimilar to my father’s voice, an accent changed by decades of living away from home. It would be how it was twenty years ago, or so, but different. I look up phrases in Cote Ce Cote La, a glossary of Trinidadian idioms. To find the voice I write an entirely different story based on an anecdote my father told me years before our interviews. That story, Jesus Saves, does not make the final Insurrections lineup. I read Rising Above and Beyond the Crossbar, a memoir by Lincoln Phillips, a former soccer coach that led Howard University’s team to two separate NCAA championships, the first for a historically black college team. My father played on the Howard team before Phillips’ time. In his memoir, Phillips details an incident that happened before he came on to coach, one my father also tells me in one of our interviews. The team, the all-black team made up mostly of students from the Caribbean and Africa, has just finished playing a team down south and is looking to grab a meal. Restaurant after restaurant turns the men away. The coach, overwhelmed by the disrespect, the illogic of the hate, right there on the bus, puts his head down and begins to cry.

+

At some point in our interviews, my father tells me about the days after Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated. The D.C. I grew up around was still damaged from those days and only fully recovered about thirty years after the riots. This is what I want to hear about, the fires, the pipe. The Safeway off H Street. It’s gone now, but was there through my college days in the late 1990s. The rage, the disappointment, the fire within that caused him to join the crowds in looting. Later, in my research, I read A Nation on Fire by Clay Risen. Safeway, the author writes, was seen by D.C.’s black community as a racist institution and their locations took heavy damage during the riots that followed King’s murder. Safeway’s main rival, Giant, was viewed as friendlier to the community and their stores remained untouched. As it were, my father took only the pipe before fear set in and as we chuckle about this. I know my story is made and I figure I’ll write it quickly, but it takes me three years and I come to understand “Three Insurrections” not just as a story, but as a love letter to my father, but also to all my family across seas and time.

* I also read Raymond Carver’s “Errand” multiple times, as well as Alan Cheuse’s “On the Millstone River: A Story From Memory.”

+++