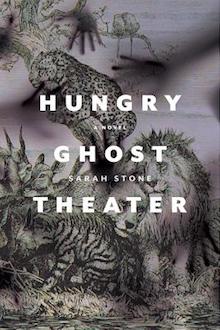

Our Research Notes series invites authors to describe their process for a recent book, with “research” defined as broadly as they like. This week, Sarah Stone writes about Hungry Ghost Theater from WTAW Press.

+

My new novel, Hungry Ghost Theater, began when I was avoiding a novel I kept writing and rewriting. That other novel changed dramatically — a pair of sisters turned into friends and then lovers, Quakers morphed into drag performers, and drinking problems migrated from character to character — but it didn’t really seem to get much better, though my friends and early readers tried valiantly to encourage me.

My new novel, Hungry Ghost Theater, began when I was avoiding a novel I kept writing and rewriting. That other novel changed dramatically — a pair of sisters turned into friends and then lovers, Quakers morphed into drag performers, and drinking problems migrated from character to character — but it didn’t really seem to get much better, though my friends and early readers tried valiantly to encourage me.

From time to time, I put it down and wrote stories and short plays about a half-Jewish family of performers, scientists, and activists, idealists who couldn’t live up to their own visions. Robert and Julia, a brother and sister who run an experimental performance company; their middle sister, Eva, an affective neuroscientist; Eva’s wild nearly grown children. And then their parents, people whose lives they touch, other performers, patients in a locked psychiatric facility. I began to feel as if these people existed somewhere: it was my job to find them and bring them over an invisible, semi-permeable barrier to introduce them to the world.

Eventually, I realized I had written most of a novel that brought in a lot of my obsessions: whatever I’d learned about Abu Ghraib, Dante’s Inferno, the neuroscience of empathy, world hunger, colliding mythologies, and various cultures’ ideas about underworlds or hells.

I have to admit that I am not a great researcher. I’m married to a writer who loves research, who will read fifteen books about photography in the early 20th century, who belongs to historical societies, and who still knows how to search out and use articles on microfilm. I, on the other hand, have the attention span of a fruit fly on a sugar high. I poke at different books, read parts of essays, hop around the internet, look at maps and photos and videos, sometimes return to and finish works, but I don’t actually master any subject, particularly if it involves abstract thinking.

So some elements of the book that only required looking back over old memories and notebooks were borrowed from life, from very-much-transformed versions of family troubles, to a couple of jobs I’d had in psychiatric institutions, to the years I’d lived in South Korea and central Africa.

Also, I’ve always been in love with the glorious collective delusion of the theater. All these people sitting together in the dark, pretending that whatever is happening on stage is real. Weeping over the death of Cordelia, again. Stretching our mind to believe and not believe at the same moment, to take in the shapes and patterns and spectacle in front of us. Over the years, I took multiple courses in acting, improv, and playwriting, which fed the book.

Eventually, two remarkable director/performers — Erika Chong Shuch and Anne Bluethenthal — let me sit in on auditions and rehearsals for their companies, the ESP Performance Project and Anne Bluethenthal & Dancers. The processes these artists went through gave me an understanding of juxtaposition and spectacle that became part of the novel’s structure and approach, as well as its content.

My natural way of working is to focus as much on characters in their groups as on each individual. Sometimes we think we are most ourselves alone, thinking (and sometimes we let our characters spend too much time alone, thinking). But we have so many different selves, and selves we never knew before can emerge in a new job or love affair, or in response to changes in a family member.

In watching auditions, I saw these kinds of changing relationships enacted very directly. By the time of audition callbacks, all the performers still under consideration had strong backgrounds and skills. So the final decisions about who would be in the piece came down to what each brought to the group and how they interacted — one performer’s fierceness and humor became more vivid set against another’s fluidity and emotional opaqueness. This translates to writing a family, where both the commonalities and the differences create the ensemble effect, and small changes in one character can transform how we read another.

Another aspect of juxtaposition showed up in rehearsals. Early on, the gestures and speech often reinforced each other, giving a sense of overfamiliarity. Or a speech went on too long, a necessary moment of exposition turning into explaining and re-explaining. When these moments were trimmed or cut altogether, the remaining words and images resonated differently. We know this about writing (particularly about other people’s writing), but seeing these transformations from rehearsal to performance, especially in companies dealing directly with political information or ideas, made me realize how much I was putting in excess research or information because I wanted the reader to have it, rather than because the characters needed it for their full lives.

And watching the intimacy of these juxtapositions of character, the spaces left after the obvious was cut away, also showed me how the spectacle I love in theater — the lights, the dramatic colors and movements — happens around these intimate moments. The book needed some central, quiet conversations. Characters had to push, advise, or coax each other into decisions in ways that felt honest and believable. Having the emotional reality in place before adding in the spectacle makes the difference between a work that feels wild but true and one that mostly functions as an elaborate light show.

All of this gave me courage in relation to some of the more extreme aspects of Hungry Ghost Theater. All the different voices and modes. The moments when my performer characters behave dramatically in their real lives. The journeys to Zanzibar, Seoul, and hell. The mixture of reality and mythology.

If the fundamental character relationships felt true, if the juxtapositions were exact, then the book might (might!) earn a level of spectacle and drama that matched its subject matter. I don’t think writers ever feel peaceful, exactly, about the risks we’re taking. But I found it helped to anchor the piece in emotional truth, and only then allow the spectacle to unfold.

+++