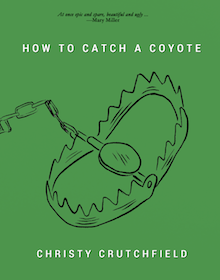

Our Research Notes series invites authors to describe their research for a recent book, with “research” defined as broadly as they like. This week, Christy Crutchfield writes about How To Catch A Coyote from Publishing Genius Press.

+

2005

The coyotes were getting brave. My friend was now living in the farther suburbs of Atlanta and told me they were eating pets, which was no surprise. But one attacked a man on a morning run, and when she yelled at another out her car window, it didn’t run away. She could hear them calling at night. I was living in the closer suburbs of Atlanta. I didn’t know we had coyotes, not in our state, not in the South. I pictured them as desert animals in a landscape of the red canyons where Wile E. chases the Roadrunner. My friend informed me otherwise. She said, “It’s really sad when you see a missing pet sign because you know it was eaten.”

The coyotes were getting brave. My friend was now living in the farther suburbs of Atlanta and told me they were eating pets, which was no surprise. But one attacked a man on a morning run, and when she yelled at another out her car window, it didn’t run away. She could hear them calling at night. I was living in the closer suburbs of Atlanta. I didn’t know we had coyotes, not in our state, not in the South. I pictured them as desert animals in a landscape of the red canyons where Wile E. chases the Roadrunner. My friend informed me otherwise. She said, “It’s really sad when you see a missing pet sign because you know it was eaten.”

I wrote this down. This had to make it into a story, which I was learning to write, which I am still learning to write. The coyotes made it into a couple terrible stories, which were thrown out. I kept my coyote sections, cut and pasted into their own file waiting.

+

2003

My college friends and I were getting braver. There was very little surrounding Elon University, and what I was learning in my classes made it hard to shop at Walmart. No one really left campus except to go the chain restaurants and Walmart. But we decided we would go further. We made friends with townies and went to the local bars. We were proud of ourselves. We saw ourselves as more open-minded than our other friends. But I was starting to feel guilty for what I would later understand as privilege. Burlington, NC is a dying mill town, a bedroom community for the upper class and a trap for the lower class. Our townie friends joined the military to get out. One served multiple tours in Iraq. Others had to move to find opportunity now that the factories were closed. We moved there for the opportunity of a liberal arts education, and there was no question that we were getting out after graduation. We protested the Iraq War and talked about it in class.

+

2006

An old friend made it into my writing often. I lost touch with her during college. I heard she was living with her dealer and then I lost her altogether. Years later, I ran into her at a gas station. We met at a Waffle House because she was on step eight: amends. I wanted penance at age 18, but I didn’t really need it in my 20s. I remembered the adolescent cruelty, but I also remembered games of Truth or Dare when she slept over, her way to test the waters before she could tell me what actually happened to her because of her family. I had been warned in high school that I would know someone who was raped. I didn’t know that by 30, I would know five women (those who have actually told me) who have been raped and many more who have been assaulted, harassed, and ruffied. But she was the first to bring this reality to light. And it was a family member that did it. It was over, she said, and had been taken care of. But looking back on it as an adult, I realized it hadn’t been.

She is not Dakota in my story, and the incident in How to Catch a Coyote is not the same as the incidents that happened in her family, but I think about her often, even after we’ve lost touch a second time. I think about her family, especially about her younger brother. We hear many stories, real and fictional, about the effect of abuse on the victim, but we don’t hear many from the “untouched” sibling. What is life like, especially when you are piecing together what happened? Especially when your parents have different versions of the story?

I found a story appropriate for the coyotes lurking in neighborhoods, present and evasive at the same time. It got me into grad school.

+

2010

In cold and stoic and wonderful Western Massachusetts, I embraced the South in a way I never did when I lived there. All my stories became southern. I accidentally started a novel. I wrote myself into a mess, I wrote away from it, and I wrote myself into a bigger mess. I gave up. I read Ander Monson’s Other Electricities and Bonnie Jo Campbell’s American Salvage, and realized what I was originally trying to do, what I had written away from for 150 pages, was possible. I scrapped everything I’d written and eventually, with so much support and help, wrote a thesis that’s now a book.

+

2011

How to Catch a Coyote is full of things I know nothing about. I did a good deal of research into North Carolina (Lafayette is a made up, composite town), how yarn factories operate, family sexual abuse, and — of course — coyotes. I learned about the awful practice of fox penning. I looked into hunting and trapping laws. I learned how to actually catch a coyote. I looked at both sides of a very divisive coyote debate. I stared at pictures of coyotes, coydogs, and traps. I got stuck in rabbit holes of coyote puppy pictures. I visited The Daily Coyote almost daily. I learned that coyotes are so adaptable they’ll probably be around with cockroaches at the end of the world. They are so evasive that they became an accidental and perfect trope to the family story in the book, even to the evasive structure of the book.

But most of my research was internal. I hate the assumption that you are your characters, that everything that happens in your fiction is personal. But really, no matter how much you write what you don’t know, no matter how far your characters’ beliefs and actions are from your own, it’s personal. I had to get into my characters’ heads and into the best and worst parts of my own. I’m interested in writing characters at their worst, and many of the characters in this novel are monsters or at least act like monsters. But I want them to be human, even if I don’t want the reader to agree with them. It may be my way to understand the real people who scare me, who I’m afraid of becoming. Not necessarily to forgive them, but to remember they are human.

+

2012

I drive by the Elon exit on my way back to Atlanta for Christmas. I see the new Target/Best Buy/Barnes & Noble shopping strips from the highway, and I feel it in my stomach. They’re identical to the ones right outside UMass.

+++