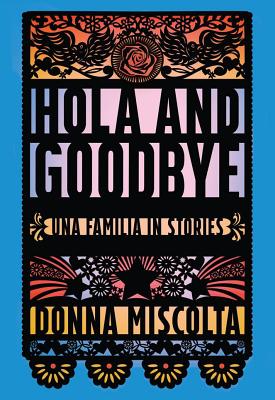

Our Research Notes series invites authors to describe their process for a recent book, with “research” defined as broadly as they like. This week, Donna Miscolta writes about Hola and Goodbye from Carolina Wren Press.

+

After my grandmother died,

there was no one to make the tamales. My mother and aunts no longer had to bother their tongues with Spanish. Ties to relatives in Mexico languished. The U.S.-Mexico border that my grandmother had crossed in 1924, a mere dozen miles from where she settled in a working-class neighborhood in south San Diego, suddenly seemed distant.

there was no one to make the tamales. My mother and aunts no longer had to bother their tongues with Spanish. Ties to relatives in Mexico languished. The U.S.-Mexico border that my grandmother had crossed in 1924, a mere dozen miles from where she settled in a working-class neighborhood in south San Diego, suddenly seemed distant.

Hola and Goodbye: Una familia in stories is and isn’t about my family. It tells the stories of family members across three generations, the first of which came from Mexico.

These are not border stories in the sense of the physical border across which people, goods, and popular culture flow, like the Spanish-language television and radio stations that played in my grandparents’ house. Like my grandmother’s regular excursions to Tijuana to get her hair done, to see a dentist, and to shop for shoes, medicine, or a molcajete. Like my grandfather’s habitual jaunts to the Agua Caliente race track. Like the occasional visit from Tijuana or Mazatlán or Guadalajara relatives who sat around my grandmother’s kitchen table for slow sips of beer and hours-long banter in Spanish.

But if Hola and Goodbye isn’t necessarily about the physical border, it is often about the borders around being brown or the borders around being female, either of which might complicate a character’s sense of identity.

The characters in the first section of the book, Four Women, come from Mexico in search of a future. One of them is Lupita Camacho, who has no time to learn English, so busy is she sorting fish in a tuna cannery alongside other immigrants, scrubbing clean the house, making her own tortillas, caring for her children whose acquisition of English will give them sway over her, and humming boleros full of longing. Her hands are big-knuckled and rough. Her hair shows signs of early graying. She is forever wearing an apron.

+

When my mother was dying,

but when she was still alert enough to look us in the eye and issue a pronouncement — because pronouncements, not conversation, were what came out of her mouth, an entitlement of age and the fact of her dying — she said in a quiet explosion of disgust, “I was a dumb mother.”

I’d never heard her say such a thing before, but I knew she had long thought it, had long internalized the sense of inferiority and insufficiency others had directed at her because she was female, because she was brown. If she was not worthy, wouldn’t her children by extension also not be? When I was young and had learned the word paleontologist, I announced that I wanted to be one. My mother laughed. “You don’t even know what that word means. You just like the sound of it.” I was too young to understand what was behind the cruelty. After many years of feeling only my hurt, did I begin to see and understand hers. But it wasn’t until she was dying that I felt the force of it — when she called herself a dumb mother.

“No,” I said, “you weren’t dumb.”

“All I did was work in retail,” she said with the same disgust in her voice. She’d never really spoken of her ambitions. Maybe she thought it was useless to have them.

My mother and my aunts married young, right after or even before finishing high school. They had children starting in their early twenties or younger. That was the way of the world then and there was no one to show or tell them differently.

In the stories in the section called Ambition, Lupita’s daughters marry and have children. They are housewives — even Lyla, who had aspired to celebrity as a dancer but whose unfulfilled dreams she had to channel through her daughters, despite their disinclination to perform, despite their need to be themselves. Millie, who finds motherhood a bad fit, might have excelled at something outside the home if she had believed an alternative was possible. But they do cope, these women who believe that something better awaits their children.

“You came out smart,” my mother told me, as if such a thing occurs magically at birth, never believing in her own untapped potential.

+

When I was in the fourth grade in 1963,

long before I knew the word feminism, I vowed I would never change my name. At ten years old, despite my shyness and painful awareness of my flaws — poor eyesight, crooked teeth, bony frame — and as much as I longed to be someone else (a blond and blue-eyed someone, for instance) — I was nevertheless committed to the idea of me, for better or worse, as the only me in existence. That singularity intrigued me. I would never alter that by taking a man’s name if I were to marry. I also knew that I would leave the place where I grew up at the first opportunity. I would say goodbye to those physical boundaries — as if that could open up those other boundaries of sex and color that hemmed me in.

The third section of the book is called Leaving Kimball Park. Some of Lupita’s grandchildren are venturing or trying to venture beyond the boundaries of their lives. They each in their own way push against the limits imposed by a legacy of low expectations, self-doubt, and scarce opportunity. And they each in their own way make some kind of progress, score some tiny win.

Though mentally unstable Bonita asserts herself in a disastrous way with an attack on her mother, she nevertheless acts upon a real emotion, after having suppressed, distorted, or denied so many others.

Oversized twins Ofelia and Norma, recruited for the boys’ high school wrestling team, battle stereotypes, ridicule, rejection, and finally each other before they resist their objectification by the world at large and return to the humanity and compassion in each other and in themselves.

+

Women and girls

overwhelmingly populate the stories in the collection. In my own extended family, women outnumber the men. They have always talked faster and laughed louder than the men. I saw and heard them more — what they said, how they joked, what they took offense at.

They talked sometimes in asides, sometimes in Spanish like a secret code, sometimes in sarcasm that could be cruelly funny, and I could detect that there were things under the surface — something wistful or resentful about things lost or denied, and I knew it had to do with being female.

Another thing my mother said to me when she was dying was, “You always had determination.”

The women in these stories have determination. But sometimes determination isn’t enough. Sometimes the world bests their determination. The women in these stories do try. They do hope. They do dream. Despite the borders around them.

+++