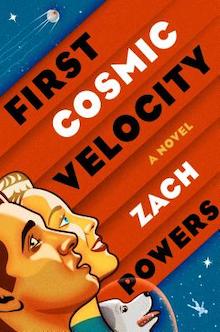

Our Research Notes series invites authors to describe their process for a recent book, with “research” defined as broadly as they like. This week, Zach Powers writes about First Cosmic Velocity from G.P. Putnam’s Sons.

+

The Search for Language: How research informs the craft of writing

I completed my initial research for First Cosmic Velocity six or seven years ago. That research was, of course, supplemented by ongoing Googling throughout the writing process. My old notes are stored in Word documents unopened since I completed the novel’s first or second draft, four documents in all: Settings, Scenes, Characters, and Details. Whenever I came across something of interest in my research, I typed out the passage or sketched out an idea. Throughout writing my first draft, I’d return to these notes periodically, scan over them and, more often than not, rediscover something I wanted to include in the novel.

I completed my initial research for First Cosmic Velocity six or seven years ago. That research was, of course, supplemented by ongoing Googling throughout the writing process. My old notes are stored in Word documents unopened since I completed the novel’s first or second draft, four documents in all: Settings, Scenes, Characters, and Details. Whenever I came across something of interest in my research, I typed out the passage or sketched out an idea. Throughout writing my first draft, I’d return to these notes periodically, scan over them and, more often than not, rediscover something I wanted to include in the novel.

For all the interesting tidbits I captured and reproduced, I was also engaged in an act of internalizing the material I was reading. No, I’m not now qualified to be a rocket scientist, but I’ve accessed the thinking of an engineer. With space exploration, there’s a striking poetry in the territory between the technical knowledge required to accomplish any feat of rocketry and the dreams of people obsessed with exploring the stars. More than any facts I discovered, I’m interested in this language, and how accessing this new language can affect how I write.

On the most practical level, research of a specialized topic introduces you to new words, or familiar words used in a new way. The title of my book, for example, is a term meaning the minimum speed a rocket needs to reach orbit. I came across this phrase early in my research and immediately inserted it at the top of my manuscript. It’s been there ever since.

Beyond the title, I was enabled to use words from rocketry throughout the novel. How often do you see “thrust” except as an unfortunate word choice in a sex scene? How often do you get to use “rocket” in its literal noun form? There are centrifuges and control panels and hypergolic fuels just waiting to be written about. I regret now not having a fifth document of notes simply called Words.

If you’re a literary writer, I’d suggest that you keep tabs on new terms as you research a subject. Collect them. Play with them in practice sentences to see how they pair with your native voice. See how they push your voice in new directions. What new rhythms can you discover? What new assonances? What new parallel word structures?

None of this is to say that every sentence I wrote contains a space-themed term. Too much of that would turn quickly obnoxious. However, once I’ve established a rhythm and syntax based on new terms in some sentences, my overall rhythm and syntax will be altered to match, at least if I’m paying enough attention to my own writing. That’s the state I aim to reach: the language of a book influenced by external sources of language. This is where my novel’s voice comes from.

Benjamin Percy hits on a similar concept in his essay “Get a Job,” included in his essential collection of craft essays, Thrill Me. The core conceit of the essay is that your characters need to have jobs because so much of our personal identities are defined by the work we do. Jobs affect how we think and how we talk. A kindergarten teacher will have a markedly different voice from a Wall Street banker.

There’s much more to Percy’s essay, but a key point for me is that we all speak different languages based on the sum of our experiences. Research can serve as the entry point for learning and being informed by these different languages. Note that being informed by a language is not the same thing as copying it. As a fiction writer creating characters, I can’t write as somebody else, but I might just be able to pull off a reasonable representation of another person. Representation does not mean replication.

The character of the Chief Designer in my novel is based on the real Chief Designer of the Soviet space program, Sergei Korolev. I borrowed details from his life, and he’s the only character who owes so directly to the historical record. However, the chapters from his perspective contain more than just a list of these details. I also imagined what words would be common in his thinking. Terms from engineering and rocketry, of course, but he had also been sent to the gulag by Stalin. How would a proud person, having survived the lowest of lows, confront his own sense of dignity? What words would he use to think about life that another person, without a memory of Siberia, wouldn’t have access to?

I enter into research hoping to find something interesting to say, of course, but I’m also looking for interesting ways in which to say things. New language is waiting to be discovered in specialized terminology, new settings, unusual details, and the real stories of people who influence the characters we create. Facts are set dressing, ephemeral, but language is a story’s building material. I’d argue that language, even when it reaches its least visible, unnoticed state, creates the gut-level reactions that readers of literary fiction are looking for.

The story you tell matters, but a successful storyteller recognizes that every story has a manner in which it’s best told. The most important thing research introduces me to is new words, new phrases, and new logical structures that exist only within certain places at certain times. Research, then, is a process of finding where the foundations of the story meet the experiences of the author, and in the space of that meeting, new, exciting language can emerge.

+++