Our Research Notes series invites authors to describe their process for a recent book, with “research” defined as broadly as they like. This week, Rebecca Entel writes about Fingerprints of Previous Owners from Unnamed Press.

+

+

I started taking notes when I visited the Bahamas — to develop an off-campus course for the college where I teach — not because I thought I’d write a book, but because jotting down words, images, and ideas on scraps of paper is something I’ve always done. Sometimes I turned the scraps into short stories. I tinkered with a story from these notes for a couple of years, returning to it as I prepared to teach the course on Caribbean literature and the environment. I became preoccupied with the strange layers of history accruing on that tiny island, which bore monuments to Columbus, the ruins of slave plantations that were transplanted from the U.S. by British Loyalists after the American Revolution, and a luxury resort. My notes began accumulating in a different way from how my stories usually did: in fragments, still, but in fragments that seemed to multiply themselves rather than stand, stubbornly clinging to themselves, waiting for me to figure out how they all went together. I hoarded them, waiting for my impending sabbatical when, with the foreign gift of time, I’d find out if I could figure out how to write a novel. I moved to a new place, spent untold hours mulling, organized and reorganized all the research I’d done, kept lengthening the list of projects I’d first get out of the way.

I didn’t know what I was doing, so I had to trick myself into writing a book. I stopped thinking about the big picture, about having a book. I stopped picturing myself from afar, fingers flying over the keys like a concert pianist, and started staring at the screen. I used the exercises I assigned when students were stuck (“Interview Your Character” or skip to a scene you didn’t intend to write or switch to a side character’s point of view). I signed up for NaNoWriMo to try daily word count goals. I set timers for writing and breaks. I joined a shared writing studio and on the first afternoon there wrote 3500 words because a writer I admired was there, too, and I knew if he saw me wasting time on Facebook, then I couldn’t possibly be a novelist. I read lots of other people’s novels, churning up arguments with myself: no, that’s what a novel’s supposed to be; you’re doing it wrong versus OK, but just keep going; maybe you’ll make your thing work in the long run.

I didn’t know what I was doing, so I had to trick myself into writing a book. I stopped thinking about the big picture, about having a book. I stopped picturing myself from afar, fingers flying over the keys like a concert pianist, and started staring at the screen. I used the exercises I assigned when students were stuck (“Interview Your Character” or skip to a scene you didn’t intend to write or switch to a side character’s point of view). I signed up for NaNoWriMo to try daily word count goals. I set timers for writing and breaks. I joined a shared writing studio and on the first afternoon there wrote 3500 words because a writer I admired was there, too, and I knew if he saw me wasting time on Facebook, then I couldn’t possibly be a novelist. I read lots of other people’s novels, churning up arguments with myself: no, that’s what a novel’s supposed to be; you’re doing it wrong versus OK, but just keep going; maybe you’ll make your thing work in the long run.

Teaching, writing, research, and immersion blurred as I returned to the island several times to do all of the above. I paged through anthropological and archaeological studies about the island and read an oral history about its communities; I talked to people and studied the English dictionaries of different islands; I went to all the places people told me to go and many of the places people couldn’t understand going. I got better at using a machete to reach the ruins of the plantations, though my form always deteriorated when a nasty blister developed on my thumb. I missed a trail entrance, going so deep inside brush the insect bites on my face looked like mumps. I then found the trail entrance, making my way to the first plantation building with relative ease, using my machete to get to another, and another — only to find that the most recent, destructive hurricane had stirred so much growth that I couldn’t get all the way back to the slave cabins. Maybe all first-time novelists find themselves in such a moment: all that practice with a machete, and there you are in need of a chainsaw.

When my sabbatical ended, I had a manuscript I kind of, sort of, maybe thought was done. I would end up rewriting the book three more times over the next two-and-a-half years, my original protagonist stepping aside to share the point-of-view and then, finally, relocating to a separate file that someday might become something else.

+

+

+

This is posed. You can’t take a selfie while machete-ing (or at least I can’t. I also can’t use a machete with my left hand). The fact that you need a machete to get to these ruins — researchers coming from the U.S. are much more focused on seeing them than locals — was one of the seeming mysteries that fueled my curiosity.

+

+

Can you see it? The ship scratched into the rock? “Ship graffiti” proliferates on former plantation buildings in the British West Indies, including hundreds of images on the island I visited. Ship graffiti was the very last detail from my research I included in the book, in the last months of the very final rewrite. I’d been avoiding doing so, even though the phenomenon epitomized one of the books’ central ideas: mere traces of stories we’ll never know. The etchings filled me with such sadness, I couldn’t find a way to say anything about them. But I had to see what would happen when the narrator discovered similar images. I decided not to give her the context of my research and just let her react to what she found. (That context can be found in the work of anthropologists Grace Turner and Jane Baxter.)

+

+

I kept trying not to get distracted by the beauty (right), so I could focus on sites such as one of the still-standing whipping posts (left). But eventually I realized I couldn’t escape how both could be seen in the same frame. The gorgeous views’ enduring effect also reminded me I was still a tourist, no matter how superior I (with my bites and scratches and students in tow) may have felt to the resort tourists (on their growling jet-skis).

+

+

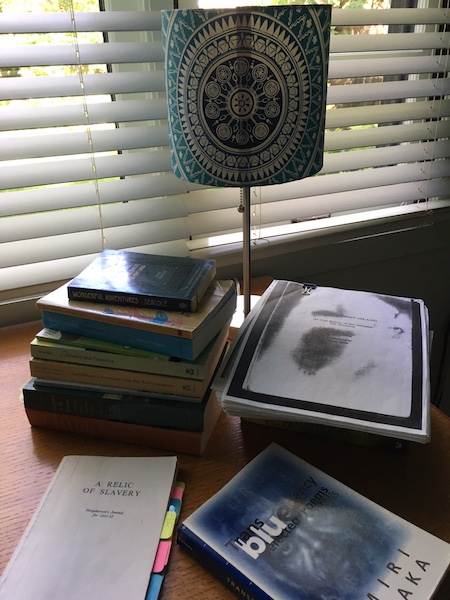

A sample of what I was reading. A few notable sources: Relic of Slavery, the only remaining Bahamian plantation journal — emblematic of the scarce fragments available about the history of enslavement: this book has missing pages and a brief mention of a slave revolt (!) before it returns to recording harvests and the weather; Paradise and Plantation: Ian Strachan’s incisive look at how the tourism industry echoes colonialism; and perhaps the outlier in this Caribbean-focused group: Amiri Baraka’s Transbluesency, which I bought about twenty years ago. I’ve been haunted by a particular stanza ever since: “And now, each night I count the stars, / And each night I get the same number. / And when they will not come to be counted, / I count the holes they leave” (from “Preface to a Twenty Volume Suicide Note”). I tried to use these lines, ineffectively, as an epigraph for a short story in my first college fiction writing class. Some research stays on your mind; there’s no direct route from what you read to what you write — and it eventually became clear one of my characters would quote from these lines in the novel. The lines also seem to sum up my writing process. I wasn’t inventing to fill a void; I was observing long enough, paying enough attention to context, to detect the holes in what I saw and account for them in some way.

+++