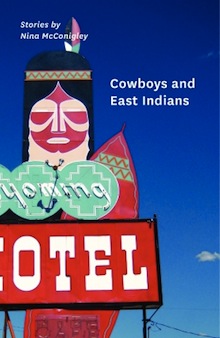

Our Research Notes series invites authors to describe their research for a recent book, with “research” defined as broadly as they like. This week, Nina McConigley writes about Cowboys and East Indians (Five Chapters Books).

+

Before I went to graduate school, I worked at the Casper Star-Tribune, Wyoming’s largest newspaper, as the Assistant State Editor. The title sounded grand, but most of the time, I edited story after story about rather dreary state news. Being Wyoming, many of the stories were about what the Game and Fish Department was up to, wolf management policies, oil and gas, and the state legislative session. All policy stories that made my head spin as I struggled to learn state procedure and laws.

Before I went to graduate school, I worked at the Casper Star-Tribune, Wyoming’s largest newspaper, as the Assistant State Editor. The title sounded grand, but most of the time, I edited story after story about rather dreary state news. Being Wyoming, many of the stories were about what the Game and Fish Department was up to, wolf management policies, oil and gas, and the state legislative session. All policy stories that made my head spin as I struggled to learn state procedure and laws.

But there were perks of the job, and one of them was to go through all the state newspapers to see if there were any stories worth following up on. In the afternoons, I would sit with a stack of newspapers from small towns all around Wyoming and just read. It was never the front page that would interest me. Instead I liked looking at the police blotter, the weddings, the obituaries, and oh, how I loved the Letters to the Editor.

At that time, I had only written a handful of short stories. I vaguely thought I wanted to write fiction, but my attempts at writing stories were a mess. As I read through those papers from towns like Thermopolis and Buffalo, I started to feel like I could never write fiction. The high jinx of small towns and the characters I encountered in irate letters and obituaries were better than anything I could make up. I felt a kind of despair that I could never create something as interesting. The truth was indeed stranger than fiction.

I started clipping out articles and filing them in folders. I had one folder titled “Oil and Gas.” In it, I clipped out a story about a rancher that had decided to embrace the excess of water that was coming out of a coal-bed methane well on his land. He welded together a metal palm tree and created an “oasis” on the dry prairie. I cut out another story about a woman who worked in oilfield man-camps, keeping the trailers and things in order. I had a whole file on the “Wyoming State Penitentiary and Honor Farm”. I was fascinated that the prisoners were breaking wild horses, that they were at one time working on a mushroom farm in Shoshoni. I still have a photo I cut out of an inmate on a large monster of a wild horse. They both look a little wild-eyed and unsure.

I made other files. One was entitled “Hunting and Fishing Mishaps”, another “Tourist Vacations Gone Wrong”. I was always amazed that a hapless tourist every few months would attempt to pet a bison and find out the result was not great. And let’s just say Dick Cheney was not the first person to shoot someone while hunting. I clipped obituaries of people I never knew. In one obituary, the family claimed the man had invented the world’s largest rake. I tried to picture it. Was it attached to a tractor, or just a supersize version of the one I used every fall to rake leaves? In another obituary, a family noted that the person had indeed been dead for two years and in that time, they had donated the body to science. But now they had got the body back and were ready for a burial.

In the whole time I worked there, I didn’t write a word of fiction. I just read and read. Occasionally, I would fill in for a reporter, and I wrote stories about the last remaining drive-in movie theatre in the state, I covered the County Fair and a local cat show. It wasn’t hard-hitting news, I just reported the daily lives of people living and working in the least populated state in the Union.

When I started writing Cowboys and East Indians, I looked back over the stories I clipped out. I began to see a kind of theme. I was drawn to strong and quirky characters. Perhaps that’s why I found the outrage of someone who wrote a damning letter to the editor because they had been cut off in their truck on 1st Street so compelling. Their action at being wronged was so acute. And I knew that the start for me with every piece of fiction, every story, was character. I wanted to write about people who felt the world very keenly, who had a point-of-view that would keep a reader reading. When I look at my collection I see a band of merry mishaps — a cross-dressing cowboy, a kleptomaniac exchange student, a medical tourist with no sense of India, a gout-ridden geologist, and Indian family running a rundown motel. The list goes on, but I knew I wanted outsiders to populate my stories.

And perhaps the biggest outsider was myself. I may not act very quirky — and in fact, I think I am a rule-follower and rather unadventurous — but the fact that I was brown in Wyoming made me stand out. It was and still is the norm for me to walk into a room and be in the minority. It has been that way all my life. I was different by the nature of my skin color. In many ways, my own experience of being conspicuous has shaped every story in the collection. I am the research. I know what’s it like to be asked “What tribe are you?”, to be followed around in a store, to be told soon after 9/11 to go back to my own country.

Every writer’s life informs his or her work. So I am nothing new in using my own life as a mine for fiction. But fiction gave me the ability to feel the kind of outrage and bad behavior I often saw in those old newspaper clippings. I may have been non-reactive about being called a name, but I sure as hell could make my characters react. I could rewrite and change my characters into something more subversive. In that way, my stories are my Letters to the Editor, my way of making my opinions known.

I still look at the folders every once in awhile. Now, people use the internet, and I am sure whomever works at the newspaper probably scrolls through webpages. But I like to think back on those afternoons of reading newspapers while drinking bad office-made coffee with powdered creamer. The things and people being reported about laid the framework of how later I would tell a story. It was in seeing the story in the ordinary, in the everyday, that I later would realize that the truest stories for me were of what I knew, the ones close to home.

+++