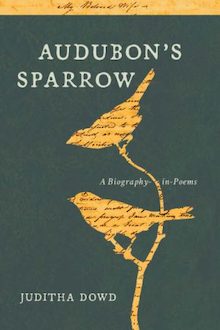

Our Research Notes series invites authors to describe their process for a recent book, with “research” defined as broadly as they like. This week, Juditha Dowd writes about Audubon’s Sparrow from Rose Metal Press.

+

Letters to the Self: Finding the Person in the Persona Poem

Ten years ago, on a bone-chilling winter night in New Jersey, I was rummaging on my husband’s nightstand for something new. Although admittedly bored and restless, I wasn’t seeking inspiration; I just wanted a good read. Randomly I settled on Richard Rhodes’ biography John James Audubon: The Making of an American, a Christmas gift from a daughter.

Ten years ago, on a bone-chilling winter night in New Jersey, I was rummaging on my husband’s nightstand for something new. Although admittedly bored and restless, I wasn’t seeking inspiration; I just wanted a good read. Randomly I settled on Richard Rhodes’ biography John James Audubon: The Making of an American, a Christmas gift from a daughter.

Rhodes had me from the first page. Nineteenth-century America was filled with dramatic events. Among them was The War of 1812, which interrupted our young country’s trade routes and led to the British burning of Washington D.C. Also, the Louisiana Purchase and the collapse of the U.S. economy caused by its loan repayment in 1819 — a crisis that brought financial ruin to many business owners, including the Audubons. Then there was John James himself — a sympathetic, heroic and maddening creature. Rhodes quotes John James: “[I was] of fair mien, and quite a handsome figure: large, dark, and rather sunken eyes, light-colored eyebrows, aquiline nose and a fine set of teeth […]” Obviously, modesty was not one of Audubon’s traits, but by all accounts he was vivacious, multitalented, and fun to be around.

The would-be naturalist started sneaking into lyric poems I was writing, but by now my attention was shifting to Audubon’s remarkable English wife, who seemed to flit in and out of the Rhodes biography like a necessary bird. Perhaps because she was the rarer catch, I longed to know better the Lucy Bakewell who played a minor role in her husband’s exciting biography. How might she have viewed the arduous early decades that shaped their long relationship, years when she lived in poverty, toiling to support her family and her husband’s ambitions?

I soon came across Lucy Audubon, a Biography, by the late Carolyn E. DeLatte, one of the few writings I could find that focused on Lucy rather than her famous spouse. DeLatte describes a charming and curious girl, the eldest of six children. She mentions Lucy’s fondness for gardening and that she owned a copy of Erasmus Darwin’s book The Botanic Garden, a brilliantly quirky blend of poetry, science, and Enlightenment thought that hints broadly at theories later developed by his grandson Charles. Lucy now had my full attention, and I realized that if I wanted to hear more from her, I’d have to imagine it myself. Time to choose a strategy and assemble some tools. Epistolary poems, I decided, would let Lucy pass along information and describe her circumstances in a chatty way. In her day, it was the only means of keeping in touch with far-flung family and friends. And letters would encourage me to think about how she viewed herself, as well as how she’d have wanted herself to be seen. Diary poems would allow me to explore Lucy’s private musings.

Both forms fall into the category of personae — the Latin word for masks, and in the dramatic sense, for characters. I needed to fashion a Lucy mask and fit it over my own face. As I’ve always thought of diary entries as letters to the self and had kept a diary as a young woman of the sort I had in mind for Lucy, I could view letters and diary entries as two sides of the same coin. Moreover, letter poems have been popular forever, and I had no trouble finding models, dating all the way back to the Roman poet Ovid’s collection Heroidies. Over two thousand years ago he took the unusual step of writing epistolary poems in the voices of mythological or historical females such as Helen, Dido and Sappho — letters full of lament, explanation, accusation and longing. Though ancient, they’re still fresh — they could have been written today. Ovid begins with Homer’s Penelope who, like Lucy, is left on her own by a husband who has undertaken an arduous journey. Ulysses has gone off to war. Audubon is away on a different quest. But Lucy, too, suspects that her husband has delayed his homecoming longer than necessary, indulging himself with other interests. Ovid’s Penelope begins her letter by asking Ulysses to return, using the simply compelling and poignant word come: “Penelope to the tardy Ulysses: / do not answer these lines but come, for /Troy is dead and the daughters of Greece rejoice.

In a discussion of Ovid’s Heroides in The Harvard Review Online, the writer J. Kates mentions So Spoke Penelope, a 2011 book by poet Tino Villanueva. Kates characterizes the book as midrash, “a literary genre […], [that] consists of taking an established canonical text and inserting narrative or psychological amplifications where they do not already exist […] a form of commentary, […] a mechanism of expansion.” I acquired a copy. So Spoke Penelope’s blend of timeless story with contemporary language is pitch perfect. Though of course Villanueva cannot have known my hopes for my own book (still in its earliest form when he published So Spoke Penelope), his poem Come to Me felt like grace, a confirmation of my own impulses.

A third type of persona poem, dramatic monologue, offered a way to deepen the narrative. In poetry, the dramatic monologue — a soliloquy — is theater on the page. The technique includes well-known efforts by Victorian poets like Robert Browning and contemporary examples like Sylvia Plath’s Daddy. The speaker’s words, not the poet’s description, tell us whatever we know. Soon I was writing what I called “she” poems, third person verse that reflected Lucy’s thoughts, emotions, and physical connection to the natural world and the man she’d marry. Here Lucy operated similarly to John Berryman’s character Henry in some of the Dream Songs — a third-person observer, watching herself. Psychologists call this “depersonalization;” it can be a useful strategy when we want to show a character’s detachment from self, especially in the face of trauma or strong emotion.

It took longer to realize that I was seeing parts of myself in the young wife of Audubon. Like me, she was the eldest child in a large family. Curious, a little vain, a bit arrogant. For all her level-headed competence Lucy, too, seemed a romantic. Newly arrived from England, at eighteen she was far from the social world she enjoyed as part of Derbyshire’s gentry; she might have been bored on her father’s new Pennsylvania plantation. But a young Frenchman living on a neighboring farm soon paid the family a welcome call. John James Audubon came from an awkward background — the illegitimate child of a ship’s captain and a French chambermaid, an ancestry he took pains to disguise. Like Lucy, he was capable, smart and athletic. Both oved music, books, dancing, riding, the outdoor life. Audubon used personal magnetism and a genuinely sweet nature to convince those he wished to impress. As he courted Lucy, he turned his charm on her family. Though Lucy’s father was never completely onboard, persistence prevailed. And yes, all this was sounding familiar…

At twenty-one I too had married a talented artist and dreamer, planning what I thought of back then as “the art life” — a future that didn’t impress my practical father. Suffice it to say that, while all this happened long ago, I had a personal perspective on what it means to sacrifice for someone’s else art. More and more I was seeing things from Lucy’s point of view, even as I remained loyal to her fascinating husband, who struggled against enormous odds to bring his dream alive. And just perhaps (I now allowed), “depersonalization” had been more my way of handling things than Lucy’s.

I could see now that what worked well in Dream Songs was not working for Lucy.. She deserved ownership of her thoughts, a measure of control I’d denied her in the third person poems. I took another look at Heroides, examining the speech of Ovid’s wronged women. Some may dismiss Ovid’s efforts as a strictly male perspective. . But in Ovid’s portrayals I find much similarity to how women in nineteenth century America might have spoken about themselves. Denied rights and power, taught to find their worth in service to a husband, the bearing of children, and running of a household — how different were they from the Greek wife in Homer’s time or the Roman contemporary of Ovid? It seems to me Ovid understood them pretty well.

Meanwhile, among other poets I consulted, one example stood out: a multi-section poem encompassing three dramatic monologues — The Ghost Trio, from a book of that name by Linda Bierds. It’s told in the voices of prominent eighteenth-century Englishmen, the first being Erasmus Darwin, grandfather to Charles), a poet, thinker and scientist — the very Darwin whose book Lucy owned as a girl. He also happened to have been the Bakewell family physician back in England and a close friend of Lucy’s father. Reading this poem felt like pulling back a curtain to view the world into which Lucy had been born.

Here are lines from the opening section (Darwin, a teenager, speaking):

1. The Winter: 1748

A little satin like wind at the door.

My mother slips past in great side hoops,

arced like the ears of elephants —

on her head a goat-white wig

Under the spell of Bierd’s craft and vivid imagination I discovered news ways for Lucy to express herself. Still, something was missing. I decided to put the manuscript away and give both Lucy and myself a rest.

Months later when I was thinking about my maternal grandmother, Mae Eastmond, it struck me that my affection for Lucy might have an additional source. Mae was born in 1884, fifteen years after Lucy’s death. She shared similar values and attributes, as well as English ancestry. Like Lucy and me, Mae was the eldest child in a large family. The daughter of a Methodist minister, she was smart, capable, hard-working and musical — she played the organ and directed a church choir. Numerous young men courted her, but she chose a handsome and adventurous bachelor eleven years her senior. Charming, able to play any instrument by ear, Lou Eastmond was a painter, gardener, collector of things — rocks, stuffed animals, rare plants. Despite his well-paying job as a train engineer — work that kept him traveling much of the time — the Eastmonds were often in debt, hovering, like the Audubons, on the brink of financial disaster.

Soon after I was born at the start of World War II my father joined the Navy. My mother traveled from port to port to be near him, leaving me in the care of the Eastmonds for weeks at a time. When my brothers arrived, three within the next four years, my mother was overwhelmed. I In some sense forever, her parents were also my parents, and I knew them in the visceral, intuitive way small children know their true caretakers. My grandmother lived to be ninety-nine. In her fifties she became a baby nurse, hiring herself out to families with newborns — not unlike the work Lucy resorted to when times got tough. After she’d stopped working for pay at 76, Mae continued to help new mothers, including me. I will never forget the week she took a train to New York and nursed me through a serious case of mastitis, while getting up at night with the new baby, caring for my three-year-old, and cooking all our meals! She was eighty-four that winter. Only long after her death, as my own grandchildren began to enter the world, did I understand how she had sacrificed her own ambitions, time, and happiness — for my grandfather, for me, for all of us who needed her throughout her long life. Lucy, too, toiled into her seventies — raising two granddaughters when their young mother died, and returning to teaching to help pay off family debt.

Today, as I was finishing this essay, I revisited So Spoke Penelope and read the introduction. It was there I learned that Villanueva had also been inspired by the devotion of a grandmother. Sacrifice is an old story with many variations, common among families and across cultures. When I acknowledged how the specifics of Mae’s particular version had influenced me, it became obvious what was missing from my poems. Recalling my grandmother, and recognizing the debt I will always owe her, had offered keys to what eluded me. And soon enough Lucy Bakewell rewarded my persistence, as she dropped her mask and at last began to breathe.

+++