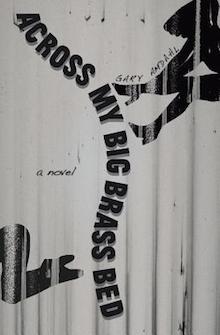

Our Research Notes series invites authors to describe their research for a recent book, with “research” defined as broadly as they like. This week, Gary Amdahl writes about Across My Big Brass Bed from Artistically Declined Press.

+

The research for Across My Big Brass Bed took place more or less without the author knowing about it — without the author, perhaps, even knowing he was an author (though indeed suspecting it from the very beginning). It took place years ago, decades ago, and was as natural to the author as breathing.

The research for Across My Big Brass Bed took place more or less without the author knowing about it — without the author, perhaps, even knowing he was an author (though indeed suspecting it from the very beginning). It took place years ago, decades ago, and was as natural to the author as breathing.

AMBBB was written in 2009. Part One, about 75 pages, was written in a week, e-mailed to Sven Birkerts at AGNI, who read it in a couple hours, and wrote to me immediately, the day I’d sent it to him, that he was going to spend the rest of the day convincing the other editors, and they’d run it that fall. I spent those next seven months writing 400 more pages. The text was unbroken, other than by a very complex and periodic syntax (there were no paragraph or chapter breaks), because the thought was unbroken, and the thought was unbroken because the trance was unbroken. (For the sake of comparison, the novel that will be published next January, The Daredevils, is constructed conventionally and has taken me twenty-five years to write. There are eight full drafts.)

I don’t mean to suggest I was doing anything like automatic writing, or so-called free-writing; I was writing very rigorously with specific goals to be reached at the end of every sentence, but I was in a sort of day-dreamy state about the books I’d read as a kid, a teenager, a young man.

I am not at all sure what eased this reverie into written being. I had been looking at some of the oldest books in my library, and feeling nostalgic, remembering where I was and what else I’d been doing when I read them. I idled happily through incoherent thoughts of how they’d made me who I am — made me the writer I am. (There isn’t much difference, but some.)

I eventually divided the novel into three parts and named each part after books that had come to stand out for some reason: The Open Society and Its Enemies, by Karl Popper; I and Thou, by Martin Buber; and Small Is Beautiful: Economics As If People Mattered, by E. F. Schumacher. (There is a very short fourth part, a coda titled Ball Four, Jim Bouton’s baseball memoir. And the novel’s subtitle is “An Intellectual Autobiography in Twenty-Four Hours.”)

Any serious reader as old as I am, 58, will recognize these books: they were all quite popular (though nothing like best-sellers). I suppose they were part of the hippie canon, and the first time around, were read as such. The second time around they were browsed about in, as I looked for questions to fuel my super high-powered but gas-guzzling sentences. This quickly became a modus operandi: everything I read was pertinent to what I was writing. I wrote faster and faster to keep up with my thoughts, which, I don’t think it’s too much to say, were hyper-inflating in much the same way that the universe is said to be doing in the wake of the Big Bang.

Two of the easiest and most important bits of research had to do with the Vietnam War: First, I wanted to find the National Geographic cover that, in 1965, had made clear to me that there was a war going on that wasn’t in the past, wasn’t a TV show or a movie or a book. It was not a war I could play in the backyard with my friends in Blaine, Minnesota. Second, I wanted to see the results of the draft lottery, which I had followed with steadily growing dread in the early 1970s. I remembered thinking, okay, I wouldn’t have been drafted this year, but that raises the odds, doesn’t it, for next year? The draft was ended the year before I came of age, but that feeling in the pit of my stomach didn’t go away. I couldn’t shake the idea that I had gone from playing war in the backyard to facing conscription in a summer. My number came up twice in four years. I told myself I would not go to Vietnam, but, like Tim O’Brien, I probably would have been more afraid not to….

More difficult research revolved around a scene in which the narrator attends a concert of Satie music. Q&A with the musician leads him to wonder if the long drawn-out silences in the “Gymnopedies” and “Gnossiennes” still somehow “contained” music, if there was music in silence — which is of course a basic tenet of the American postwar avant garde, Cage et al. My narrator stops there for the time being, but I followed the idea to Charles Ives, who famously asked, “My God! What has sound got to do with music?” His “The Unanswered Question” led me to Emerson’s The Sphinx:

The perception of identity unites all things and explains one by another…and the most rare and strange is equally facile as the most common. But if the mind live only in particulars, and see only differences (wanting the power to see the whole — all in each) then the world addresses to this mind a question it cannot answer, and each new fact tears it to pieces, and it is vanquished by the distracting variety.

And to Thoreau:

The falling dew seemed to strain and purify the air and I was soothed with an infinite stillness… Vast hollows of silence stretched away in every side, and my being expanded in proportion, and filled them. Then first I could appreciate sound, and find it musical.

Because my narrator wants to live in an open society, because he wants to relate to people in communion, I and thou, rather than in any kind of mediated or regulated way, and because he believes that small is beautiful, his music puts him on the street, playing Bach’s cantatas on a bandonéon. While I was bringing him there, I listened to Bach’s cantatas, all two hundred of them, almost nothing but for six months. I read Sir John Eliot Gardiner’s excellent liner notes for his Bach Cantata Pilgrimage recordings, which took place in 2000, and Albert Schweitzer’s Bach. Most strangely, I also read the passages in the Bible that Bach and his librettists used as their raw material.

+++