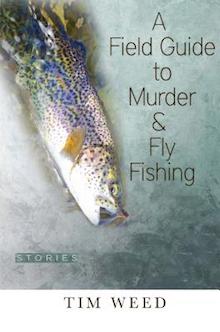

Our Research Notes series invites authors to describe their process for a recent book, with “research” defined as broadly as they like. This week, Tim Weed writes about A Field Guide to Murder & Fly Fishing from Green Writers Press.

+

Some fiction writers start with concept or character. I start with place. Not place in general, but a specific place: a place I’ve been, a place that’s infected me, a place that’s lodged itself barnacle-like at the tideline of my imagination. A granite quarry deep in the hemlock forests of New Hampshire, or a warren-like maze of alleyways in southern Spain. A Cuban city eclipsed by rolling blackouts, or a tidal flat where quick shadows streak across a sand bottom in three feet of clear green water. A jungled river in the Orinoco basin, or a mountain summit towering above a snow-blanketed ridgeline like the colossal tombstone of some ancient king.

Some fiction writers start with concept or character. I start with place. Not place in general, but a specific place: a place I’ve been, a place that’s infected me, a place that’s lodged itself barnacle-like at the tideline of my imagination. A granite quarry deep in the hemlock forests of New Hampshire, or a warren-like maze of alleyways in southern Spain. A Cuban city eclipsed by rolling blackouts, or a tidal flat where quick shadows streak across a sand bottom in three feet of clear green water. A jungled river in the Orinoco basin, or a mountain summit towering above a snow-blanketed ridgeline like the colossal tombstone of some ancient king.

Once I’ve found one of these places — or better said, once one of these places has found me — I’m drawn inexorably back. To walk around. To taste the air. To absorb the sights and sounds and textures and smells. To scratch whatever itch of dread or fear or redemption has been awakened within me.

When I was writing the thirteen stories contained in a Field Guide to Murder & Fly Fishing, the act of returning sometimes meant taking an actual, physical trip. More often — and more useful, honestly, when it comes to creating fiction — the return was accomplished in a wholly imaginary way. Whether actual or imagined, the trips had to be repeated again and again, through dozens and even hundreds of revisions. Such behavior may strike those who are not fiction writers as obsessive-compulsive. Call it OCD if you like, or shamanic meditation, or the writer’s equivalent of an oil painter’s pentimenti. Whatever the correct term, in the writing of these stories, each return trip resulted in a clarification, or an exaggeration, or a deepening emotional refraction.

“All good books are alike,” Hemingway once wrote, “in that they are truer than if they had really happened and after you are finished reading one you will feel that all that happened to you and afterwards it belongs to you; the good and the bad, the ecstasy, the remorse and sorrow, the people and the places and how the weather was.”

Every story I’ve written — even the ones that have ended as failures (and there have been many) — live on in my memory like unforgettable dreams. If a story fails, it’s because I haven’t been able to bring those dreams alive in a readers mind with the same intensity that they came alive in mine. In the successful stories, the dream has allowed itself to be captured. Put in a bottle, so to speak. Only the bottle is the printed page, and when you read the page — or so I hope — the captured spirit of the place wafts up.

As writers, part of our job is to figure out what it is, specifically, that makes our most vivid imaginings come alive in the mind of another human being. In my case, I’m certain, a good portion of that fairy dust is to be found in the setting. To the extent that any research was important to the writing of A Field Guide to Murder & Fly Fishing, it was not archival but field-based research, research that involved a deep and sustained contemplation of the real and imagined world. Most of this research was of a straightforward, sensory nature: What, exactly, does this place look like, sound like, smell like, taste like, feel like?

As a species, we’re ruled and dominated by our over-developed hominid imaginations. Setting is what propels us into the dream of story, because its lucidity — its sensory concreteness — activates our imaginations on a subconscious level, irresistibly, without our knowledge or permission. Immersive fiction, in other words — if its truths are to exert their resonance on the deepest levels of our psyche — must evoke a vivid and immediately recognizable story-world. I’ve found that for me, a sustained effort over countless iterations is required to create story-worlds that feel “truer than if they had really happened.”

I must admit that it isn’t only literary ambition — the mercenary urge to create fiction that’s as gripping and immersive as possible — that has driven me to revisit those places I’ve found most inspiring. I return also because of the numinous spirit I’ve encountered in those places, which is hard to pin down but impossible to ignore. A spirit that is connected somehow to the hidden, vibrant, pervasive force that animates all existence. Because I suspect that what writers are really talking about when we talk about the importance of a sense of place in fiction has to do not only with the ways a setting plays out in a reader’s subconscious mind, but also the ways it taps into the collective unconscious — the universal mind.

And this gets us to one of several reasons, I believe, that fiction is of value to humanity beyond just serving as a distraction or an entertainment. It’s well known, for example, that reading fiction is an antidote to loneliness, and that it increases readers’ empathy for people whose lives and experiences are quite different than their own. But fiction can enhance our moment-by-moment appreciation for our natural and cultural surroundings. It can inspire readers to explore those surroundings more mindfully, both within the vast expanse of the human imagination and out in the wider world. And this in turn, perhaps, can inspire us to cherish and more actively protect the planet that has spawned us.

+++