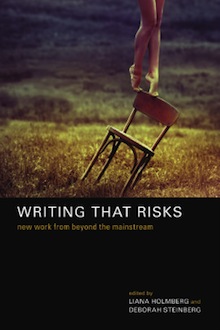

Three innovative authors — Jenny Bitner, Jønathan Lyons, and Catie Jarvis — published in the new anthology Writing That Risks: New Work from Beyond the Mainstream talk with editor and Red Bridge Press founder Liana Holmberg.

+

Liana Holmberg: Your styles range from surreal to experimental. In this book, there’s a shapeshifting kindergartener, a conversation with God, and a story that reveals itself through erasure, all of which shake up readers’ expectations. What does it mean to take risks in your writing?

Liana Holmberg: Your styles range from surreal to experimental. In this book, there’s a shapeshifting kindergartener, a conversation with God, and a story that reveals itself through erasure, all of which shake up readers’ expectations. What does it mean to take risks in your writing?

Catie Jarvis: The risky part of my writing is being true to the stories and ideas that inspire me, that serve my work, even if they might offend or confound the people that read them. I enjoy sharing my writing, especially with the people closest to me. What I express in words is an important aspect of who I am, it’s intimate, and at the same time it reaches out, elicits a response. When I write a story like “The Poisonous Mushroom,” where we meet a shapeshifting God and a Holocaust victim who deplores him, I realize that there are people who won’t understand what this story “means,” and others who might be offended by the sentiments of the piece.

Jenny Bitner: One of the lines in my story “We Heart Shapes”, that’s in the anthology, is “Well it depends on how you feel about children and sex.” Every time I read that line I think, hmmmm, well, yeah, how do I feel about children and sex? We know how divided the country is on the subject, but even within ourselves we can be divided. How do we feel about sex when it comes to our own children, and how much do we try to control their sexuality?

The story is a futuristic, fantastic tale about a boy who shapeshifts into different animals. He shapeshifts into a bonobo along with some other children, and they start acting like bonobos, one of the most sexually uninhibited animals, petting and fondling each other.

I took a draft of this story to a writing workshop, and one of the members said that the ending “seemed like pedophilia.” Well, that certainly wasn’t what I had in mind. It almost made me not want to finish the story. I have a small child and am protective against sexual exploitation of children, but I am also interested in the freedom of children. We have known since Freud that children have intense sexual lives and yet we try to make them seem like little neutered beings—very safe to have around the house.

After the workshop, I edited the story to make it clear I was not sexualizing the children for adults’ entertainment. But maybe the ending still seems too sexual to some people. I don’t know. I don’t know if there is any way to write about children and sex and not risk being risky. But without a risk, what is on the line?

Jønathan Lyons: I think the biggest risk I’ve taken in my writing—and the most rewarding—has been to toss the so-called rulebook out the window in favor of creating new forms. Those new forms still need to function on their own terms to be readable, but this reconsideration of my approach has allowed me to rethink the possibilities for how, exactly, a story might unfold, how the various components and details of a tale might be revealed, and how to present the subordinate components in relation to the moment that the story hinges upon. And I think that what’s been risky about that has been the chance that any resulting piece might be written off as unpublishable. (This has happened to me, once from a journal whose guidelines specified that they were seeking experimental fiction.) Sometimes you get lucky; sometimes you find the right editor, the right publisher, the right audience, and the crazier innovations work.

LH: When you write, you’re each putting yourselves on the line—taking chances with form and controversial topics—but it seems that one of the biggest things that’s at stake is still managing to make a connection with readers. Every deviation from “safe” storytelling poses a dare to the reader: Follow me into the unknown, where you might get uncomfortable and the outcome isn’t guaranteed. How do you get readers to take the dare, to follow you into a risky story?

JL: I have to admit, when I started the process of putting stories together like this, I really didn’t have a strategy for hooking the reader, or luring the reader in. I hoped that the story and the form would be compelling enough to intrigue readers enough to come along for the ride.

CJ: Writing, for me, began as a way to connect with people, to move them, but as my writing grows it yearns to be “different.” This makes it more difficult to get things published, and more difficult to share with the people around me when it does go out into the world. When I finished grad school, I gave my grandpa a copy of my poetry chapbook for his 87th birthday. I’d been giving him my writing since I was in elementary school. My grandpa was a sharp and well-read man, he always appreciated my work, but this time after reading my collection he said, “I liked that other stuff you used to write. I could understand it.”

In some way his comment pleased me. There is a reason why we writers push. The goal is not to be easily understood, but to maybe, possibly, open some teeny-tiny door that hasn’t been opened before. Often, we fail, and there’s no door revealed. Sometimes there is one, though! Not everyone will be able to find the door, or if they do find it, not everyone will care to look through. But it’s worth trying. It’s worth giving the reader that opportunity to see something they never saw before.

JB: As a reader I want the author to take risks, and I assume the same of others. When I am reading something and nothing is at stake or nothing seems passionate or pushing the boundaries, then I often get bored. Toni Morrison said, “If there’s a book that you want to read, but it hasn’t been written yet, then you must write it.” I guess that’s what I’m trying to do. I want to be moved, scared, shocked, aroused and made to reconsider things in my life and feel things deeply by writing.

LH: Name one book you can’t stop going back to.

JB: I love Jeanette Winterson’s Written on the Body. I’ve been wanting to reread Never Let Me Go by Ishiguro. Also very fond of Aliens and Anorexia by Chris Kraus. A book that I read for inspiration sometimes is Roland Barthes’ A Lover’s Discourse.

CJ: I’m not usually going back. I’m usually reading something knew. Right now, Beautiful Ruins by Jess Walter. A combination of an innovative narrative and a story that’s impossible not to connect to. For me, that’s perfect. But I do always return to Lorri Moore, Paul Bowles, and T.C. Boyle’s If the River was Whisky.

JL: Naming one is tough. Steve Erickson’s Our Ecstatic Days is one I marvel at all the time. I love how Rick Moody challenges the notion of what details and characteristics comprise a good story in his collection Demonology, which really should have included his controversial short “A Good Story.” Rikki Ducornet’s fabulism takes my meager mind to the cleaner every time. But Erickson’s novel is the first that comes to mind.

LH: Ducornet’s The Complete Butcher’s Tales continues to provoke and inspire me, especially when I’m writing against the grain of realism. What is your relationship to realism? What do you find when you play outside the box?

JL: That depends; some of my experimental forms deal with magical realist/fabulist elements. To me, experimenting with expectations in fiction means possibly doing so with expectations for realism, as well.

JB: I think surrealism and fantasy can often be as realistic as realism. Realism is like a nest of ideas of what we believe to be true about reality, but it does not take into account the unconscious mind, dreams, trance states that we are living much of the time, the past and the future. If we take all those into account, then we realize that the nest is one idea of what is real, and perhaps very cozy at times, but not reality. What is real and what is not real becomes more slippery. I like to play in that slippery space.

CJ: I intend to write realistic stories, about people and situations that compel me, but an element of other worldliness always makes its way in. I guess I don’t see the world as being strictly one way or another, sometimes the most “real” people, ideas, and emotions, are best conveyed surreally. Plus, when I play outside the box I get really excited and think that I’m way more innovative and creative then I probably am. Maybe that’s why I ultimately do it.

LH: What’s your favorite word today? First word that comes to mind?

CJ: I like Contessa. There’s a regalness. An Italian countess, or, more interestingly, the brand of my first guitar that my mom gave me.

JL: Oddly, I was thinking of the word concubine, how close it is to Columbine, and the kind of tractor called a combine that keeps turning up in my toddler’s books of words.

JB: Patty-cake.

LH: Do you have questions for one another?

CJ: Something about form… What’s an innovative form you tried for a story that either failed or succeeded?

JL: It’s funny, but I wrote a short called “Dashiell” that obsessively broke the show/don’t tell “rule,” telling everything and showing almost nothing. It worked really well and several publications wanted it. Then I tried to use the same approach and it turned out to be this bloated, not-clever, obvious piece of garbage. A dismal failure.

JB: I have one story that is all questions. Does it work? I’m not sure. Do you think it would work?

+++

Catie Jarvis is an author of fiction and poetry, as well as a yoga instructor, a competitive gymnastics coach, and an online writing instructor at Ashford University. She received a BA in Writing from Ithaca College and an MFA in Creative Writing from California College of the Arts. She grew up on a lake in northern New Jersey and now lives with her husband; her cat; and her bird, Echo, by the ocean in Marina del Rey, California.

Jønathan Lyons lives and writes in Central Pennsylvania. He teaches writing and literature at Bucknell University. His writing has appeared in the Journal of Experimental Fiction, Hotel Amerika, Exquisite Corpse, and elsewhere. He received an MFA from California College of the Arts.

Liana Holmberg writes fiction and poetry. She is the founder of Red Bridge Press and a freelance developmental editor.