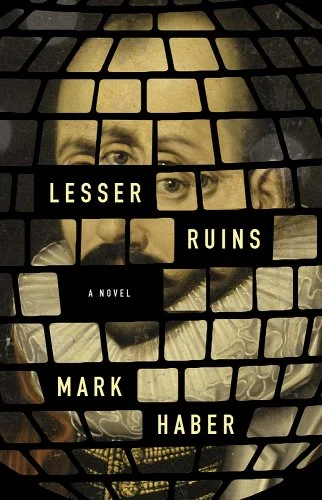

Coffee House Press, 2024

A novel in three paragraphs, Mark Haber’s Lesser Ruins is no beach read. In an all but unbroken 276-page stream of prose, Lesser Ruins probes the deepest crevices of the brain of its narrator, a middling community college professor and self-described “Montaignian” whose lifelong, and frequently destructive, obsession with the philosopher lurches him to the edge of despair in the wake of tragic loss. What begins as a comic exploration of academic fixation swiftly becomes heart-wrenching. The result is a breathless literary experience that touches the narrator’s roving mind to the reader’s own.

Lesser Ruins takes off by announcing its narrator’s intentions. Following his wife’s death, the professor seizes the chance to make headway on a long-term academic project: “Anyway, I think, she’s dead, and though I loved her, I now have both the time and freedom to write my essay on Montaigne.” Although the death of his wife is present from the novel’s first line, the professor’s early musings are often discordant with this loss. Her death is one of the many ruptures within the isolation he so desires.

His career-spanning interest in Montaigne notwithstanding, the professor hasn’t managed to write a word. Instead, he’s spent his time reading, researching, and brainstorming possible titles for this work. (“Lesser Ruins” is one of them.) To write, after all, would require vast spans of uninterrupted thought. These are the conditions of “slow thinking,” or, to use the professor’s preferred term, the “mental Saharas” the modern world is constantly breaching. (The professor is a fan of italics, a visual gesture toward the typographic momentum he cannot reach.) Titles, on the other hand—mere gestures of ideas—occur to him in droves. They signal the limit of what feels possible when he is so rudely interrupted by phone chirps, coffee cravings, and increasingly, grief. Like the armchair anthropologist the professor invokes with repeated references to a landscape that is not his own, the titles are relics of an outdated time, the “lesser ruins,” perhaps, of the manuscript he was never able to complete.

The story of his wife’s sickness emerges in flashes between long-winded discussions ranging from the history of coffee to Montaigne’s relationship with Russian intellectuals to the “endless intrusion” of students, whose very presence he finds dulling. When sorrow does intrude, it remains confined to incomplete clauses: “[…] and what a strange word, I think, family, wondering if it’s even a family when only two remain.”

Eventually the professor can no longer contain his grief within his syntax of repression. Inside a single, devastatingly tender sentence, his interrupted love story bursts to the surface:

and when the bar closed she invited me to her room and once inside it was like breathing underwater, each of us taking large strokes through the boundless depths, and we did this blissfully and ardently as if a connection had always existed, something unspoken but understood, both of us swimming in unison while also independent of the other, our lungs vast and expansive, a whole host of cliches to describe our first night where blissfully we made love then fell in love and stayed that way, meaning in love, for decades

It would be a mistake to suggest the professor’s full emotional range—from dissociation to impassioned feeling—begins and ends with his wife. Along the way, Lesser Ruins treats its readers to complicated explorations of friendship and fatherhood. The professor’s son, Marcel, is an experimental DJ specializing in electronic dance music, a modern expression of sound his father struggles to differentiate from the mindless buzz of smartphones, as ubiquitous in the world as is “the odious weight of mourning” in their lives.

Crucially, it is neither Lesser Ruins’s improbable depth of emotion nor its hyperarticulate obsessions that make it such a compulsive, yet oddly delightful, reading experience. A deft storyteller, Haber knows exactly when the reader begins to feel at ease with the frantic beats of an even more frantic mind—and trusts the reader to come along.

+++

Mark Haber was born in Washington, D.C. and grew up in Florida. His debut novel, Reinhardt’s Garden (2019), was longlisted for the PEN/Hemingway Award. His second novel, Saint Sebastian’s Abyss (2022), was named a best book of 2022 by the New York Public Library and LitHub. Mark’s fiction has appeared in Guernica, Southwest Review, and Air/Light, among others. Mark lives in Minneapolis.

+

Chiara Naomi Kaufman is an MFA candidate and educator at Arizona State University and an Associate Editor for Hayden’s Ferry Review. Their writing has received support from the Wesleyan University Hamilton Prize, The Key West Literary Seminar, and BackDraft Live: a one-time Guernica workshop. She looks forward to reviewing more books in the near future.