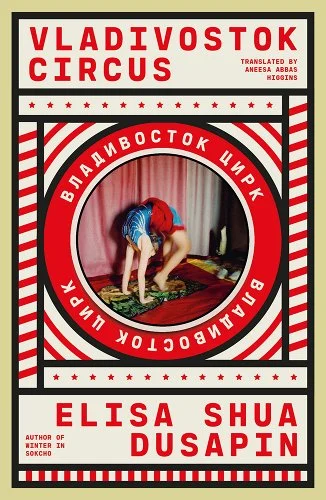

Open Letter Books, 2024

To make a novel about a circus solemn and subdued is a singular feat, and one Franco-Swiss-Korean writer Elisa Shua Dusapin accomplishes effortlessly in Vladivostok Circus. More interested in painting dreamlike landscapes and tapping into characters’ innermost isolation than in delivering a spectacular show, Vladivostok Circus drops readers in the starkness of the Russian Far East during a circus off-season. Ghostly and understated, the novel is a series of almosts: a budding relationship, an aborted performance, people on the cusp of friendship.

Central to the story is the discipline of Russian bar, in which two people, balancing a fiberglass bar on their shoulders, support a third, an aerialist who leaps onto the bar. Synchronicity is key; bases Nino and Anton are the supports while Anna “sets the beats, a rhythmic pulse, rising and falling […] a beating heart at the center of the ring.” Their coming performance at a circus festival in Ulan-Ude, near Mongolia, is the axis around which the novel swings.

Protagonist Nathalie is a young French costumer commissioned by the circus to dress its three Russian bar performers. The importance of their act to the plot makes Nathalie, an outsider to the circus and to Russia, an outsider in her own story. For some time, she lives alone in a hotel some distance from the circus and struggles to connect with the troupe. She is intimidated by Anna, making their relationship tense and awkward, and her apparent attraction to Leon, the act’s director, only further isolates her. Connections, too, are a balancing act, one Nathalie cannot sustain. When Nino offers space in one of the circus’s caravans, she remains aloof. Even the mewling of Leon’s cat, Buck, is not enough to move her. One night, she leaves him outside, in the snow, his “sound soon drowned out by the wind.” “I feel guilty,” she notes, without acting on the feeling.

Nathalie’s isolation is compounded by the setting’s severity. Dusapin’s Russia is bleak and surreal, a topography à la Tarkovsky in which things are hazy, cold, and empty. Even when reaching Ulan-Ude, the site of what sounds so bright and grand—a circus festival, of all things!—the troupe’s train passes “disused factories, cranes swaying precariously. Water towers for ghost cities. Aircraft marooned on the steppe as if waiting for fuel.” This vacant setting makes the circus feel more like a place out of a dream, a tiny world in which only the book’s characters exist, practicing their routines, “propulsion, suspension point, return to earth,” until the end of time.

Despite their intense commitment, nothing comes easily to the troupe. Nathalie’s first attempt at costumes, for instance, is an abject failure; Nino develops an ear infection, which could impact his balance; the music that accompanies the routine is terrible. Her propensity for isolation leads to clumsy interactions which, in turn, compel her to conclude that the circus, like social interaction, is a series of failures, of falling, of terrible accidents. Despite this, the Russian bar team remains optimistic, perhaps because they must in order to complete their routine. Without good humor, their act would never leave the ground.

Propelling the story is Dusapin’s delicate prose, translated carefully by Aneesa Abbas Higgins. Higgins expertly aligns the book’s original French with a soft, understated English. Indeed, Dusapin’s writing is a master class in subtlety. Nathalie’s sexual attraction to Leon is portrayed quietly, a simple staring “at his hands, the lines of veins on his forearms.” Nino’s commitment to his craft is shown not through his words but by his bruising, the permanent purple staining of his right shoulder. Even Anna’s record-breaking execution of four perilous triple jumps is only mentioned in a single sentence and then moved on from, swept into the biting wind.

Vladivostok Circus is like a tightrope, pulled taut but never snapping, and its intentionally unsatisfying ending may alienate some readers. For those interested in a cerebral trip to a circus on the Russian steppe, however, this novel can provide.

+++

Elisa Shua Dusapin was born in France in 1992 and raised in Paris, Seoul, and Switzerland. Winter in Sokcho (2016), her first novel, was awarded the Prix Robert Walser, the Prix Régine Desforges, and the National Book Award for Translated Literature.

+

Aneesa Abbas Higgins has translated books by Elisa Shua Dusapin, Vénus Khoury-Ghata, Tahar Ben Jelloun, Ali Zamir, and Nina Bouraoui. Seven Stones by Vénus Khoury-Ghata was short-listed for the Scott-Moncrieff Translation Prize, and both A Girl Called Eel by Ali Zamir and What Became of the White Savage by François Garde won PEN Translates awards. Her translation of Dusapin’s Winter in Sokcho won the National Book Award for Translated Literature in 2021.

+

Noelle McManus is a writer-poet-linguist from New York. Their work has appeared in The Women’s Review of Books, Amsterdam Review, Redivider, Eclectica, LIBER: A Feminist Review, and elsewhere. In 2023, they were selected to take part in the National Book Critics Circle’s Emerging Critics Fellowship.