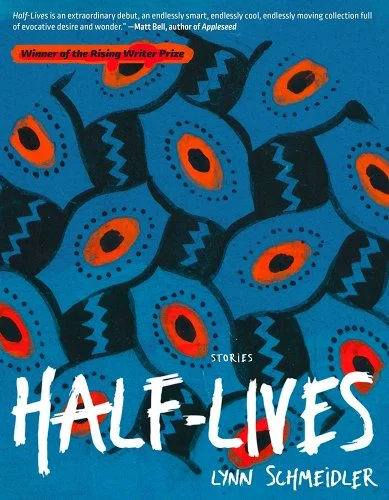

Autumn House, 2024

In the titular story of Lynn Schmeidler’s debut collection Half-Lives, a poetry teacher whose half-formed twin lives like a monster in her uterus, visits a nuclear power station with her students. She calls the creature the Hydra, after the mythical beast that grows two heads for each one that’s severed, and it is both her intimate companion and the monster that consumes her. From marriage to bodily autonomy, the stability of identity, and the relationship between mind and matter, Half-Lives questions that which we take for granted, destabilizing the foundations upon which experience is built.

The “half-lives” of Schmeidler’s title have a double meaning. A half life can refer to unstable atoms undergoing nuclear decay or to the length of time for which stable atoms survive. Schmeidler’s characters also exist in a state of becoming or unbecoming. These women are only half there, partially present, composites who are mirrored in others. Or they are women in disguise, disappearing or appearing, who make no sense or who defy the laws of physics. There is a dead girl still conscious, a gallery intern whose voice is captured only on an enigmatic tape, a menopausal woman slowly vanishing from her own life. These stories ask: Must a woman always live a half life?

Schmeidler’s stories are founded on quirky, troubled conceits: the dead girl lies in state in her mother’s yoga studio, a woman rents a tiny house that may be sentient. If these stories occasionally fall somewhat flat, as in “The Future Was Vagina Forward,” in which a woman rents her vagina on AirBnB, they mostly fizz with tantalizing intrigue.

Schmeidler pushes the limits of the probable within the possible. In “Invented,” a woman convinced she has imagined her husband into being realizes that none of us is quite as real as we think.

Told from three points of view, “I You She” is a meta-fictional investigation of identity and its disintegration. The narrator “was, of course, a writer,” a bisexual wanderer who fucks and falls in love, moves across the world, and finds it “hard to be a person.” “You nearly lost your mind, but instead found your creative power,” recounts the narrator at the end. It could be the tagline for Half-Lives.

Schmeidler’s characters, always female, are often artists—writers, painters, and performers who can only assert themselves through absence and impersonation, in a conscious distancing from the self’s core. What does it mean, Schmeidler’s stories ask, to split the self, whether in sex and childbearing or by making art? For the dead girl in “Corpse Pose,” death is a “Near-Life Experience.” But even in death, the female body cannot escape alienation. Her body becomes a totem for her community, a source of ritual, comfort, and obsession. Then, as her community trickles away, she is left abandoned in the studio, “the perfect daughter — self-sufficient and safe.”

The collection asks questions about the act of creation, for women and artists and women who are artists — the former photographer who “specialized in double-exposed self-portraits,” the Stevie Nicks impersonator who, out of costume, is “afraid of everything,” the poetry teacher with her “Hydra” or “fetus in fetu.” Pregnancy recurs as a motif reflecting both the creative act and a preoccupation with female bodily autonomy. Western engagement with spirituality is another theme. Ideas about spirituality, solidarity, and transcendence are brought into tension with their individualistic, commercial co-optation: “Yogis could repeat all there is is the present moment all day long, but nothing was as puissant as a baby-faced dead girl to bring the message home.”

The collection’s themes and narratives fall together in the penultimate story, “Deep Hollow Close.” Convinced her husband is having an affair with their neighbor, a woman known only as the Writer breaks into the neighbor’s house where she stumbles upon a secret room filled with her own lost and forgotten belongings—Raggedy Ann dolls and broken watches and still-bloody miscarriages. She’s compelled to return to the scene of the crime, which is, after all, her life: “she didn’t want to go; she had to.” Like the Hydra in “Half-Lives,” her neighbor is both part of her and a threat to her carefully-constructed identity. Like the Writer inundated by “the lost frames of her life,” I was at times overwhelmed by Half-Lives. Yet like slowly disintegrating radioactive matter, Schmeidler’s tales stick. Just as “half-lives are never over,” these stories are charged with a nuclear energy, thrumming with a tensile power that may or may not be deadly.

+++

Lynn Schmeidler has published fiction in Conjunctions, Georgia Review, KR Online, The Southern Review, and elsewhere. She is also the author of a volume of poetry, History of Gone (Veliz Books, 2018) and two poetry chapbooks published by Grayson Books: Curiouser & Curiouser (2013), which won of the Grayson Books Chapbook Prize, and Wrack Lines (2018). She earned a BA from Yale University and an MEd from Lesley College. She and her husband live in the Hudson Valley.

+

Helena Constance Aeberli is a writer and researcher from London, with a research focus on internet culture, feminism, eating disorders, and the history of medicine and the body. Her Substack, Twenty-First Century Demoniac, aims to take a closer look at what we’re missing when we get stuck in a doom scroll. Her short fiction can be found in Lunate Journal and the Oxford Review of Books, among others. She procrastinates at @helenarambles on Twitter.