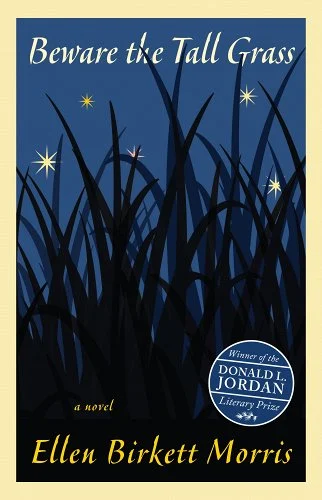

Our Research Notes series invites authors to describe their process for a recent book, with “research” defined as broadly as they like. This week, Ellen Birkett Morris writes about Beware The Tall Grass from Columbia State University Press.

+

Truth in Fiction

I was in the car on a road trip with my husband in 2014 when we heard a story about children with past life memories on National Public Radio. The story centered on a research program at the University of Virginia and the work of neuroscientist who explored the phenomena of young children with past life memories and attempted to verify the children’s claims by checking them against reportage from the times. One example was a young boy who claimed to be a World War II fighter pilot killed at Iwo Jima and correctly named the plane, a friend who was killed, and the circumstances around the death.

The idea of children with past life memories grabbed me and would not let go. I don’t believe in ghosts, have never had a supernatural experience, and don’t watch scary movies, but the dramatic potential of the story captivated me. I would spend the next eight years crafting Beware the Tall Grass, a novel that took a straight ahead look at the dilemma of a mother who wants to build the perfect childhood for her young son, whose consciousness is shadowed by memories of life as a soldier in Vietnam. As the novel progressed, I added a second POV character, a soldier serving in Vietnam.

The novel became a story of advocacy in search of answers, courage in the face of the unknown and above all love. Beware the Tall Grass details the struggles of parenthood and war, neither of which I have experienced firsthand. Of course, writers delve into unknown worlds every day. But, what draws us to those worlds and why? I wrote vividly enough that the novel won the Donald L. Jordan Award for Literary Excellence. The judge for the prize was Lan Samantha Chang.

When I started, I didn’t think to ask what drew me to these topics or how the struggles I wrote about related to my own experience. I was a firm believer that fiction is made up and the idea of a link to my own experiences offended my sensibilities.

I can still remember my indignation and disbelief, when I was approached after my MFA graduate reading at Queens University and asked if a short story I’d just read was true.

The story, “Religion,” from my collection Lost Girls, details a lonely virgin who accidently wanders into a La Leche League meeting and decides to stay. She lies about having a baby and goes so far as to bring in her own milk with the use of herbs and a breast pump. She wants connection so badly that when her milk comes in she breastfeeds a friend’s child on the sly.

Did this guy not understand fiction? Did he imagine my side gig was as a wet nurse?

My outrage was based in part on my belief that women writers aren’t taken as seriously as male writers and their craft isn’t valued as highly. Was it inconceivable that I, a childless woman, could conjure the experience of wanting acceptance, of longing for connection so badly that my character would do anything to get it?

As I wrote on Medium:

How often do male fiction writers get asked if their stories are true? Was Fitzgerald accosted and asked to give the real location of West Egg? Did Chekhov field inquiries about whether or not he ever slept with a lady who owned a Pomeranian? How often was Phillip Roth asked about his masturbation habits?

Albert Camus said, “Fiction is the lie through which we tell the truth.” This means that by building worlds that are so particular they ring true, and by digging deeply enough into the thoughts and desires of our characters, writers are able to depict situations that ring with emotional truth. We are able to reproduce feelings of desire, jealousy, lust and fear that readers recognize as true to their own experience. That is the magic of writing.

Still questions of how much of ourselves we put into our work intrigued me. As a student at Queens University in Charlotte, I asked my mentor David Payne, a fiction writer, about the memoir he was working on that would become Barefoot to Avalon. He said up until writing the memoir writing had been like having a ventriloquist dummy on his lap who was turning the fodder of his life into stories. Fiction was the filter through which he understood his life.

In an interview with me for the Southern Review of Books Payne offered a larger metaphor for the process of self-exploration embodied in his fiction writing. He said:

Standing back from them, the books started to feel like this long investigation that I had been engaged in without realizing that I was engaged in it, until some point maybe in the in the middle. It’s a matter of asking who I am and who my family is and exactly how one comes out of the other. The books were a lifelong investigation in which I saw myself or see myself as the victim, as the detective, and ultimately as the criminal as well. And by criminal and crime I mean my tendency to repeat many of the same harms that I’d been harmed by, the very ones I’d set out to understand, expose and put an end to for my own sake and my children’s.

This conversation helped prompt me to explore my fascination with a story that seemingly had no connection to my own, a story of a mother’s advocacy and a soldier’s courage. Only then did the parallels emerge. I was born prematurely in 1965 and my own mother fought to make sure I was fed because I was so small that the nurses were afraid to pick me up. When the time came she found a surgeon to perform tendon release surgery that allowed walk flat on my feet. She was my steadfast advocate in making sure my teachers did not dismiss my intellect on the basis of my limp.

As I was writing Beware the Tall Grass, my mother was diagnosed with late stage lung cancer. When I look at Thomas the soldier’s courage in the face of unpredictable challenges I see my mother navigating the medical system looking for a cure. I see myself in the schoolyard during recess trying to find my place with my peers.

Graham Greene said, “Childhood is the credit balance of a writer.” As writers, the challenges of our lives are transformed and played out through our fiction. Our stories are retold in ways that help us understand what it means to live. If we do it well enough our particular challenges become universally recognized by readers. That is where we find truth in fiction.

I found my truths on the page in Beware the Tall Grass through the dual themes of a mother’s advocacy as her young child struggled with disturbing memories and a soldier’s courage in facing the unknown, just as advocacy and courage had been played out in my mother’s struggles and my own as we sought to navigate unexpected challenges. As Albert Camus observed, “Fiction is the lie through which we tell the truth.”

+++

Ellen Birkett Morris’s novel Beware the Tall Grass is the winner of the Donald L. Jordan Award for Literary Excellence, judged by Lan Samantha Chang, and is published by CSU Press. She is the author of Lost Girls: Short Stories. Her essays have appeared in Newsweek, AARP’s The Ethel, Oh Reader magazine, and on National Public Radio.