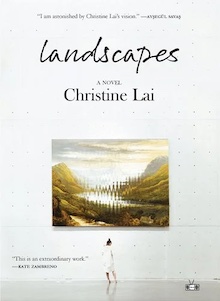

Our Research Notes series invites authors to describe their process for a recent book, with “research” defined as broadly as they like. This week, Christine Lai writes about Landscapes from Two Dollar Radio.

+

Ruinenlust

At one point in my life, I was obsessed with the English Romantics, who were obsessed with ruins and fragments. They collected and wrote about architectural fragments from the ancient world; celebrated fake ruins; composed fragmentary texts; and reimagined newly built structures as wreckage. The boom in urban construction during the Regency era ironically inspired thoughts on decay and impermanence; construction and ruination were kin. In this manner, Percy Bysshe Shelley pictured the collapse of Waterloo Bridge in London, and the architect John Soane wrote a story in which his own house has become a future ruin visited by archaeologists.

The image of the ruin was thus lodged in my mind. Later, when I encountered the dilapidated houses in the novels of W. G. Sebald—Somerleyton in The Rings of Saturn, Iver Grove in Austerlitz—I began sketching the outlines of an estate fading into decay and oblivion.

The ruin speaks of time, of its unfolding, and the way its passage traces a life or an individual consciousness. The ruin is a remnant of a lost wholeness, yet it is also a reminder that something has survived, that not all has been reduced to rubble, and what is to come might denote a new kind of futurity. The semi-derelict house thus seemed an apt setting for a story about loss, preservation, and the possibility of rebuilding.

+

Bricolage

When I first began contemplating a career in writing, I aspired to be the figure of the scholar as epitomized by Walter Benjamin in Gisèle Freund’s photograph, bent over his books at the Bibliothèque Nationale, living a life of order and intellectual rigor. But in reality, there were scarcely any long days of reading and writing in libraries. Instead, there were short bursts of time stolen here and there; fragments written in between long commutes, chores, meetings, administrative tasks, and hundreds of student papers; notes scattered across different notebooks, random sheets of paper, post-its, index cards, and countless computer files.

At first, the dispersed notes and piece-meal manuscript induced a sense of chaos, dizzying and bewildering. There were times when, after a long hiatus away from the book, I would momentarily forget what it was all about, and would have to crawl back to a space of clarity during my brief two-week holiday. Eventually, I learned to embrace the fragmentariness and discontinuities, which came to define the form of Landscapes itself. The accidental, and what Sebald calls the “haphazardly assembled materials” unearthed during the research process, led me down unexpected paths. The book grew organically, without a blueprint, guided by contingency. Writing as collecting, as bricolage.

+

Ekphrasis

I aspire toward a kind of ekphrastic fiction: narratives that arise from the process of looking at and thinking through works of art. I gravitate toward literary texts that engage with art, everything from Homer’s description of Achilles’s shield to Middlemarch’s Dorothea in the Vatican Gallery and Lily painting in To the Lighthouse, to contemporary works such as Maria Gainza’s Optic Nerve (translated by Thomas Bunstead).

For me, writing always begins with the visual. I surround myself with postcards or facsimiles of paintings, sculptures, and photographs. Thus cocooned, I drift from one specific image into a sentence or a scene. The resulting narrative is one in which the flow of events is slowed or disrupted by ekphrastic encounters, much like how a particular view of trees outside the window takes me out of the present moment and back to a Turner painting.

For a new project, I am trying to think through the photographs of Kineo Kuwabara, Daisuke Yokota, and Werner Bischof, among others. Somewhere in this labyrinth of images is a book. But for now, I sit and look, waiting for the emergence of words.

+

Quotidiana

Landscapes is divided into three parts – a diary; essays on art; and a more traditional third-person narrative. The vast majority of the novel is composed of the diary entries of the protagonist, Penelope. I am drawn to novels that are either partially or wholly written in the form of a diary or notebook: The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge by Rainer Maria Rilke (translated by Edward Snow); The Forbidden Notebook by Alba de Céspedes (translated by Ann Goldstein); The Wall by Marlen Haushofer (translated by Shaunt Whiteside); Ash Before Oak by Jeremy Cooper; and Drifts by Kate Zambreno. The diary form retains an unfinished and aleatory quality, resisting the perfection that characterizes more polished or plotted works. That quality of ongoing-ness opens up possibilities.

The notebook or diary captures the quotidian, the daily thoughts, observations, and sensory experiences that define an individual life. It is also a repository for memories, for images. Walter Benjamin referred to his notebooks as “the daintiest and cleanest quarters,” in which all his stray thoughts could be housed. Franz Kafka described his diary as the only place where he could “hold on.” “In the diary,” Kafka writes in one entry, “you find proof that in situations which today would seem unbearable, you lived, looked around and wrote down observations, that this right hand moved then as it does today.”

In a lecture, Italo Calvino spoke of how he composed Invisible Cities over the span of years, one fragment at a time, so that “what emerged was a sort of diary which kept closely to [his] moods and reflections.” Following in Calvino’s footsteps, I deposited everything into Landscapes: the artworks I encountered; the objects I loved; my observations of passersby on the street; and, above all, the books I read, for the text is a continuous conversation with the books that populate my daily life. Novel-writing, too, could be a form of diary-keeping.

+++

Christine Lai grew up in Canada and lived in England for six years during graduate studies. She holds a PhD in English Literature from University College London. Landscapes was shortlisted for the inaugural Novel Prize, offered by New Directions Publishing, Fitzcarraldo Editions, and Giramondo. Christine currently lives in Vancouver.