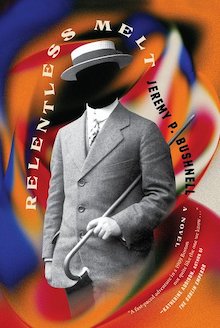

Melville House, 2023

In 1909, as the first electric lights are installed in Boston, Artie Quick, the young heroine of Relentless Melt by Jeremy P. Bushnell, wonders: Will they leave the world open to deeper inspection, or will they simply erase the shadows she likes to disappear into? The answer is both and neither. Indeed, Bushnell’s Boston is filled with shadows and half-observed mysteries that are gripping until light is cast on them. As Artie investigates everything from the roots of petty crime to a sustained scream in the night, what begins as a serious, detective-inspired, coming-of-age story sprawls into something more akin to a clever YA fantasy primed for sequels—full of magic, government conspiracies, and heroic kids.

The story begins at a gallop, three minutes before Artie’s first course on Criminal Investigation at the YMCA’s Evening Institute for Young Men. A precocious seventeen-year-old, Artie has disguised herself as a boy, wearing her brother Zeb’s clothing, in order to attend. Zeb disappeared into the criminal underworld a year earlier, and his absence has left an emotional hole Artie desperately longs to fill, if not by finding him then at least by studying crime to understand why he left. The short-lived course doesn’t provide those answers, but it does give Artie a detective role model in the fatherly Professor Winchell. Going around Boston with Theodore, a young man who fills his time with eccentric hobbies (photography and studying magic chief among them), Artie tests her new observational skills in the field. Soon enough, a series of uncanny, seemingly disparate occurrences coalesce into a sinister plot.

The partnership that develops between Artie and Theodore is based on mutual goals and appreciation rather than affection. Both outsiders seeking belonging and identity, they recognize themselves in each other. Bushnell imbues their relationship with a subtle ambiguity. Aloofness hovers over every interaction, while their social differences—Artie is a carpenter’s daughter and Theodore, the scion of a rich family—add tension. Theodore is oblivious to Artie’s feelings of inferiority, rebelliousness, and need. At times these feelings are couched in political commentary designed for a contemporary audience, but musings about gender roles and hierarchies ring true in Artie’s youthful voice: “She doesn’t care that she looks like exactly what she fears herself to be, a weird swearing girl in a suit jacket, standing on a Boston street corner with a head full of questions.”

There is an insatiable quality to Bushnell’s writing that is reminiscent of serialized novels. Peculiar characters and encounters breed questions which slowly build into a thick and sustaining structure, simultaneously organizing the novel and propelling it forward. Why does Theodore’s troubled magic teacher, Gannet, display a strange interest in Artie? What is a homeless man so desperately trying to communicate that, as a last resort, he hands Artie his fallen-out tooth? Why does Professor Winchell suddenly disappear and cancel his class without explanation? Bushnell excels at writing characters who are simultaneously rich and reticent. A shiftless film-noir mood permeates the book. Even Artie’s long hours at work in a bargain basement department store take on an air of menacing possibility, as though a ticking clock were hanging over her head.

Time is the novel’s weakness. Its awkward title is a reference to Susan Sontag on the time-stopping quality of photography: “Precisely by slicing out this moment and freezing it all photographs testify to time’s relentless melt.” As Relentless Melt unfolds, Bushnell shifts his focus from the book’s animating questions and central mysteries to uninspiring ideas about time. Waiting for Theodore to open a magical door and interrogate his teacher Gannet, the narrative swerves into the first of many out of place revelries on the fragility of time. Bushnell writes:

The tissue of time seems suddenly, perilously thin, as though it might tear. [Artie] has no idea what might lay beyond it, and contemplating the notion makes her feel lightheaded, dizzy. She tries to blink the feeling away. She wants to reach out and touch the wall to counteract the yawning sense of vertigo opening up within her but she has a sudden fear that maybe the wall isn’t real, that her hand might pass through it, that she might tumble, and fall, and keep on falling, through a hole ripped in time.

As an articulation of the angst that accompanies maturation, the novel is largely excellent—yet the final third is saturated with ideas and dramatic actions that depart from what has come before, sacrificing the strongest elements of the novel, its plot and characters, for a cinematic finish that is less satisfactory than its excellent characters deserve.

+++

Jeremy P. Bushnell is the author of two novels, The Weirdness (2014) and The Insides (2016), both published by Melville House. He teaches writing at Northeastern University and lives in Dedham, Massachusetts. He is also the cofounder of Nonmachinable, a distributor of optically interesting zines and artists’ books.

+

Willem Marx is an editor, translator, and teacher from Brooklyn by way of Vicenza. His work has appeared in Publishers Weekly, Foreword Magazine, and elsewhere. He reads for Electric Literature and writes for himself.