Novel Research in 3 Images

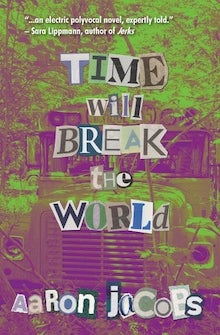

Our Research Notes series invites authors to describe their process for a recent book, with “research” defined as broadly as they like. This week, Aaron Jacobs writes about Time Will Break the World from Run Amok Books.

+

1.

My novel, Time Will Break the World, is inspired by the 1976 Chowchilla Bus Kidnapping. This was a major crime that stunned the country in the midst of bicentennial celebrations and was then immediately forgotten by most people. It involved a school bus hijacked by three gunmen who forced over two dozen students into vans before stashing them in a buried moving van in a rock quarry. I thought the story would be an incredible setup for a novel.

When it came to research, I had options. There have been articles and books written about the crime. A made-for-TV movie and several TV news documentaries have been produced about it as well. But I realized there was a problem. This source material suffered from hindsight. The books and documentaries already knew the ending—the kids and the bus driver dug themselves out and escaped. Despite the emotional trauma, no one suffered serious physical injuries. I wanted to know what it felt like to be a member of this community in the moment it was happening, as the story unfolded, when it seemed as if children had disappeared, and no one knew how or why or if they would ever been seen again. I wanted to understand how the story was being told before it ended. This led me to the Fresno Bee, the local newspaper that covered the abduction. I got a subscription to the digital archives.

The Bees coverage is a fascinating mix of fact and speculation. The people in town rightfully assumed that the kids were kidnapped, but no one had a handle on who was responsible. One article shared a theory that political radicals were the culprits. Or else it was the work of professional career-criminals. The police received a report that a white van had been seen traveling the same route as the bus, but it turned out to be a mobile dental clinic. Authorities received another tip about a short story called “The Day the Children Vanished,” leading police to take a trip to the library to check out the story. Reading the articles, I was able to see that, for the reporters, it was sometimes hard to distinguish between possible truths, realistic fears and concerns, and worst-case scenarios based on rumors and mob mentality. This insight helped me greatly when creating the psychological make-up of the characters.

+

2.

I’d started writing a fictionalized version of the kidnapping, but it wasn’t working. Partly this was because of my own limitations as a writer. I’d never tried historical fiction before. More than that, I was daunted by the long shadow of great California novelists—Steinbeck, Didion, Ellroy. I naively thought I could make things easier for myself by grounding the story in a world I was more acquainted with. So, the 70s became the 80s, and Central Valley, California became Hudson Valley, New York. That helped, but not enough.

I was alive in 1984, but my memories are the memories of a second grader. Still, I was fluent enough in pop culture—the music, the movies, the clothes—to sprinkle in appropriate details throughout the book. And yet, I understood them to be what they were: window dressing. A question remained of what larger implications about American society could be drawn from its trends. “When Doves Cry” is a cool song, but what does it tell us about being alive in the mid-80s? Does Wendy’s Where’s the beef? commercial signal anything about the way people moved through their day?

What I needed was a compendium of data from which I could draw my own conclusions. Here entered The World Almanac and Book of Facts 1985 Edition.

The almanac itself was a product of the time in which it was published. It was a New York Times bestseller and sold well over a million copies in hardcover. It has facts about pretty much everything you can imagine. But beyond learning the price of milk and the number of Ford Escorts manufactured that year and the most popular dog breed according to the American Kennel Association (Cocker Spaniel), I started to see that the information the Almanac prioritized reflected the values of that era. After all, the book was written by people. Someone had to decide what information was included and what was omitted. Several categories such as, The Top Ten New Stories, America’s 25 Most Influential Women, Heroes of Young Americans: The Fifth Annual Poll, and Leading Uses of Home Computers were able to give my writing a greater authenticity of the period than watching Miami Vice reruns ever could have.

+

3.

One of the reasons I set my novel in 1984 was because I wanted the kidnapping to take place on the same day that Mary-Lou Retton won the gold medal at the Los Angeles Olympics. I’d decided to make one of the kidnappers an Olympics obsessive, gifting this otherwise incurious young man with knowledge of the sports festival that I myself didn’t have.

I was lucky to find a book on Internet Archives that gave me what I was looking for. The title tells you everything you need to know. The Olympics: A History of the Modern Games begins with Baron Pierre de Coubertin’s late-19th century dream of a worldwide amateur athletic competition and ends with the 2000 Games in Sydney.

I liked the idea of the kidnapping and the Olympics occurring at the same time because I thought it would juxtapose a big patriotic win for the country with a shameful loss. It would show that no matter how high our successes, we were still a violent and callous nation. As I learned more about the Olympics, however, I realized that rather than contrasting the darker aspects of American society, the Games had much more in common with our culture, the grand spectacle distracting us from all that is barely concealed beneath the surface and forever threatening to expose itself. Despite the International Olympic Committee’s stated goals of promoting ethics, diversity, and peace, the governing body had proven to be politically- motivated by corruption, favoritism, and cynicism. Recognizing this let me add a layer of complexity to my character’s personality. His love of the Olympics was no longer a disconnect between who he wanted to be and who he really was, but an ironic statement of how his fandom reflected his true self.

+++

Aaron Jacobs is the author of the novels Time Will Break the World and The Abundant Life. Other writing of his has appeared in Tin House, CrimeReads, Alaska Quarterly Review, The Main Street Rag, and elsewhere. He lives in the Catskills with his wife and dog.