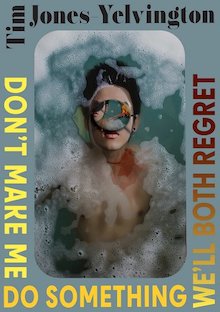

Texas Review Press, 2022

This collection of dizzying and dazzling dystopian fairytales propels the reader through a sexually intriguing, violent, shy, erudite, and disingenuous mind—think Glee Club and High School Musical meet American Psycho. In these stories, image and surface are exploited and controlled by a series of sexually obsessed narrators. “You are only whatever text I write across your face,” says one of these narrators, “however I chose to manipulate your image.”

The stories are a welter of caprice, sadomasochistic fantasy, casual sexual violence and objectification. Innocent beautiful schoolboys are corrupted throughout. Jones-Yelvington plays with genre, veering into fanfiction with a made-up story about One Direction, and into fractured fairy tales, with a reworking of Hansel and Gretel in which a boy is killed in the woods for his shoes. The writing is knowing, sly, and at times, breathtakingly lovely. It is also absolutely of its time: biblical characters are non-binary, queer characters state their desires without shame or apology, and while consumerism is skewered, the book is peppered with brand names and fast food. With villains, predators and bad fairy godmothers stealing innocence, voices, and lives, these warped fairy tales are cartoonish and fey, neon and loud, subtle as a drag act.

Physically, the book is intriguing and non-conformist too. Collage and doodles abound. The typography is interesting. Some pages contain only a couple of sentences. Others present a whole biblical pastiche with appropriately gothic typeface and blanked out passages. Paragraphs are separated by black teardrops, and wild red whorls surround chapter headings.

Tense and perfectly paced, “Cathedral Ceilings” is the tale of a gay blind man going to dinner with his best friend from college and her husband, who was once their lecturer. The suburbanisation of the formerly achingly-cool student-poet is brilliantly captured through her clothing, the food she serves, and the echoing spaces of her McMansion. Jones-Yelvington poignantly renders his blind protagonist’s insights about being observed and not able to observe in return: “I realize that you’ve never felt, nor will you ever feel, this visible or invisible.” Whether the protagonist actually has sex with the husband and stabs him, or whether it is a fantasy, is moot. The spiteful asides and nuances are delightful. Remembering his host as their grad school teacher, the narrator recalls cringey details: “I could smell you coming long before I heard you; doused in one of those douchebag body sprays that, I’m not ashamed to say, always makes me erect.”

“American Boy” features a character called #AlexFromTarget and is a camp pastiche of the boy-next-door fantasy. The hero, a valet in training, echoes characters in novels like Little Women, in which girls were expected to curb their speech, their tempers, and their desires, to develop their domestic skills and please their fathers. Like one of those girls, #AlexFromTarget is exhorted to remain sedentary and sew diligently. He pursues an unattainable ideal, fighting to be good, to conform, to complete tasks, to maintain excellent posture and to reform his tomboyish behaviour. Putting an up-to-the-minute twist on Victorian values invented to subjugate girls, the hero embroiders a sampler: “Tweets speak louder than words.”

Jones-Yelvington shows an undeniable talent for macabre and violent story-telling. In “We Are Going to Wilmington, North Carolina!,” the narrator has kidnapped a beautiful jock from his high school, the object of fevered and increasingly horrifying romantic and sexual fantasy. Throughout the ordeal, during which the pin-up boy is held captive in the trunk of a car, the kidnapper imagines in turn being rescued, protected, and in love with his prisoner. The juxtaposition of syrupy love fantasy and offhand brutal violence is powerful, ending in a psychopath’s hope of a movie ending on a beach even as the life gurgles from his dying hostage.

“Teenagers Need” cleverly entwines pornography and the things teenagers may or may not need— “a government to offer us hope,” “a life, a guiding mother.” The narrator mentions that “in real life, I spent my adolescence staring at boys I never touched. I doodled in my notebooks, let my mind wander into fantasy.” This piece feels like one of those notebooks, offering a direct line into a mind obsessed with adolescent beauty, with control and manipulation, and with the gothic, the horrific and the downright disturbing.

Jones-Yelvington’s prose veers from the bluntly pornographic to the lyrical. Some of the stories feel repetitive and the shock value suffers. But this enfant terrible can write; a firm hand on the editorial tiller would have made this collection superb.

+++

Tim Jones-Yelvington is the author of three previous works of fiction, This is a Dance Movie! (Tiny Hardcore Press), Strike a Prose: Memoirs of a Lit Diva Extraordinaire (co•im•press), Evan’s House and the Other Boys Who Live There (Rose Metal Press), and two volumes of poetry, Become on Yr Face (DIAGRAM/New Michigan Press) and Colton Behavioral Therapy (Gazing Grain Press).

+

Educated in the West Indies, Saudi Arabia, Scotland and Belgium, Elizabeth Smith studied modern languages at Durham University in England. She reads anything she can, especially pre-war books by obscure women and modern European writers. She lives in an old house on a small island where she often pretends it is 1936.