In the opening short story of Renee Simms’

In the opening short story of Renee Simms’

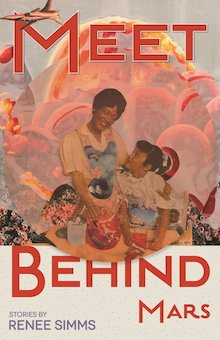

debut collection Meet Behind Mars (Wayne State University Press), protagonist Hattie attends a literary conference and receives a disappointing manuscript critique. Her novel is rejected because it doesn’t conform to the stereotypical tropes readers and publishers ascribe to and look for in black fiction. Lacking drugs, hip hop, and guns, Hattie’s manuscript presumably features unconventional black characters and/or black characters in unconventional spaces. Simms’ opening story serves as a metaphor for her collection. The eleven short stories in Meet Behind Mars take place in Arizona, California, and Michigan; in pawn shops, writers’ conferences, and in automotive crash safety testing labs. The collection features black women who are adoptees, evacuees, and expatriates, who become wives, parolees, and reunion planners. These characters navigate losing their homes in natural disasters, receiving terminal cancer diagnoses, and caring for eccentric aging parents, and they fight back by clinging to their dreams of writing novels, building drone airplanes, and challenging the sexist and racist precepts which would limit their actions and options.

I recently spoke with Renee Simms about her short story collection Meet Behind Mars, cultural and physical displacement and the importance of place in her fiction.

Congrats on the publication of your debut collection! Please tell us about the process of creating your collection. How did you put the collection together? How long did it take for the stories to become a collection? What determined the arrangement of the stories within the collection?

Thank you! It feels good to have these stories out in the world. I started thinking about the stories as a collection several years after I’d published a couple of them in the early 2000s. As I began thinking of the stories as one unit, the themes that emerged and that made them cohere were alienation and displacement. My characters all struggle with feeling out of place either because they’ve had to move to another state due to a hurricane or because their community has been bussed to a school outside of their neighborhood. For these characters, displacement is directly related to our nation’s history of antiblackness. In other stories like “Rebel Airplanes” and “High Country”, the alienation that characters experience is shaped by their social identities but it’s more generalized; it’s the alienation we all feel living in societies that privilege traditional institutions and insist that we feel successful, beautiful, prosperous, healthy, etc.

Thank you! It feels good to have these stories out in the world. I started thinking about the stories as a collection several years after I’d published a couple of them in the early 2000s. As I began thinking of the stories as one unit, the themes that emerged and that made them cohere were alienation and displacement. My characters all struggle with feeling out of place either because they’ve had to move to another state due to a hurricane or because their community has been bussed to a school outside of their neighborhood. For these characters, displacement is directly related to our nation’s history of antiblackness. In other stories like “Rebel Airplanes” and “High Country”, the alienation that characters experience is shaped by their social identities but it’s more generalized; it’s the alienation we all feel living in societies that privilege traditional institutions and insist that we feel successful, beautiful, prosperous, healthy, etc.

As I wrote the stories I kept referring to two quotes, one from Harryette Mullen’s Muse & Drudge and one from Lorrie Moore’s Birds of America. Their words would remind me of these two ideas: displacement rooted in black experiences and the absurdity of contemporary life. And their writing reminds me that humor and inventiveness is what makes writing and reading fun.

As far as arranging the stories, I purposely began the collection with a character who struggles to adapt to her surroundings and I ended the collection with a character who demands that the people in her community get on the same page with her. With the stories in the middle, I paid attention to how each story landed or resolved as I considered which story should come next. Sometimes that meant paying attention to the imagery of final scenes, the words in final sentences, or the length and pacing of a story.

How long did it take for the collection to find a publication home and what was that process like?

Probably four years, give or take. I entered a couple of book contests, sent the manuscript to a couple of small presses during open submissions. I also spoke with one editor and one agent. But I wasn’t really invested in that process. It’s a grind. And I was working on a novel which I thought that I’d sell first and have the story collection as a later publication. Then a friend mentioned that her publisher was looking for manuscripts, so I gave the stories to her. Annie Martin, the acquisitions editor at Wayne State University Press at that time, said she liked the collection and wanted to publish it.

Any advice for aspiring writers out there working on their debut collections?

Cultivate your own voice and style as a writer. Use your own obsessions as the material of your fiction. These are the things that make writing unique. I think it’s easy to become interested with literary market trends because we’re flooded with that information on social media, but at the end of the day, being authentic is a surer route to publication.

What is the significance of your collection’s title? What does it mean to meet behind Mars?

Well, the character in the titular story, Gloria Clark, says that meeting behind Mars means that she can travel wherever she damn pleases and expects good things when she shows up. Gloria says this is in response to micro-aggressions and everyday racism that she experiences in a fictional town in Washington state. She also explains that “meet behind Mars” is a lyric from Cheryl Lynn’s 1978 song, “Star Love”. So, to a certain degree, the final story explains the title of the collection. I guess I’ll add that, for me, it was important that the reader know that this collection is concerned with black women, their visions and aesthetics, and that concern is signaled in everything from the subject matter of the stories, to the title of the collection, to the cover art which is by poet and visual artist, Krista Franklin. Generally speaking, black women experience a particular type of alienation and displacement that has crossed time and space. There are endless “isms” thrown at us that we have to swerve and contort ourselves in order to miss. Generally speaking, no matter where we live, we are pushed to the margins of society, ignored, silenced, and erased, but we also have not let that deter us. We claim the entire universe as ours.

Who are your literary parents? Which, if any, seminal works influence or impact your own style or thoughts about writing fiction?

In addition to the works of Mullen and Moore, I consider Toni Morrison and Gayl Jones as writers whose work I admire deeply. I teach Jones’s Corregidora and it amazes me how much my students relate to and “get” this really weird and difficult novel which speaks volumes to me about Jones’s talent. E.L. Doctorow is another writer that’s been a huge influence. Ragtime is the novel I wish I had written and that’s always in the back of my mind as I work on my novel. I want to write a novel with that type of historical breadth, knowledge, and imagination. And I know it may not be popular to say this, but I learned so much from Philip Roth. I remember reading the scene in The Dying Animal where David Kepesh’s older lover finds the used tampon of the younger lover in his bathroom wastebasket. Kepesh arrogantly denies knowing how it got there. In response, the older woman throws the tampon at Kepesh and when he asks what he should do with it, she says, “Why don’t you put it on your bagel and eat it?” I remember reading that and thinking, this is how a writer who is unafraid and free writes. All of Toni Morrison’s work communicates fearlessness and freedom as well.

*In the opening story “High Country,” the protagonist’s manuscript about a black girl coming of age in 1980s Detroit is panned at a writing conference because “It isn’t Romance. It lacks drugs, sex, hip-hop, guns…” That line feels like the collection’s mission statement as well as a critique of the publishing industry’s expectations that black literary fiction fit a certain mold. Please address the work you intended for that line to do. What’s at stake for you in your writing? *

This is such an easy question to answer, LOL! What is at stake for me in my writing? I guess I want to get things down on paper — people, places, experiences — that are true to what I’ve observed. And I also want the freedom to explore people, places, and experiences that are curious to me, that I don’t know personally. I think those are two reasonable and perhaps basic desires of any writer, but the marketplace and hegemonic thought make it difficult, at times, for black artists to explore their full range. I think the publishing industry has gotten better since the time I wrote that line initially. My publisher has published very different books by black women writers including Vievee Francis, Rochelle Rile, Rae Paris, Desiree Cooper, and francine j. harris. And there have been publicists like Kima Jones who have transformed the industry by choosing to focus on women writers of color, working with small presses, and articulating our work to the general public in ways that no one else has.

Several of your stories make reference to characters’ adaptability, resilience, and buoyancy. Why is adaptation an important concept in your fiction? What are the rewards for adaptation and what are the costs for those who fail to adapt?

Adaptation makes up a good portion of human history, I think. We adapt to or surroundings in order to survive. And within the process of adaptation there’s often resistance and a reshaping of the external environment. So, I think adaptation resonates for me as a concept for those reasons: it allows me to think about how people reconfigure and are reconfigured by place.

Your story “Who Do You Love?” is the only one in the collection to feature a male narrator and POV. How do you imagine this story fitting in with the overall collection?

That’s a great question. What that story has in common with the other stories in the collection is the theme of displacement. The male narrator, Trevor, is a first-generation immigrant to the U.S. He’s a bit homesick when he meets a woman, Priscilla, who reminds him of women from his homeland of Jamaica. While he sees something familiar in her, she pushes back in a couple scenes. She lets him know that she’s not familiar, pliable, or known to him, that she is her own person and African American. “Who Do You Love” features a male POV but Trevor’s gaze is very much focused on Priscilla, trying to figure her out beyond the stereotype and what he doesn’t know.

Many of your characters express feelings of emotional or physical disorientation accompanied by physical displacement i.e. a sense of being culturally, emotionally and physically out of place. Additionally, the stories in your collection seem to be very deliberately set in Midwestern and western locales, some of which are black enclaves and some of which are predominantly non-black spaces. How important is setting/locale/place or “locus” to your fiction? What does it mean for your characters to exist and/or thrive in these spaces?

I would love to see more fiction about black Midwesterners. Midwestern culture is so dynamic and it varies depending on if you’re in Chicago, St. Louis, Indianapolis, Detroit, or somewhere else. When I was growing up in Detroit, many of the elders had moved there as part of the Great Migration and so there were similarities with black southern culture.

I think place is very important to characterization and plot. One of the reasons that Hattie’s alienation in “High Country” feels heightened toward the end is because of the setting. If she were vacationing in a city with lots of people of color, and sitting in a coffee shop, I’d have to work harder to communicate her loneliness and confusion. By contrast, when you place Hattie in the Sonoran Desert, way above sea level, with characters she doesn’t fully understand, her anxiety and awkwardness become more legible and easy to dramatize.

You’ve had a previous career as an attorney. How did you make the transition from being a lawyer to a writer and a professor? What connection, if any, is there for you between law and literature? Are there ways in which your law background influences your current writing practices?

I am working more and more to make connections between these disciplines of law and literature. There are writers like Karla Holloway at Duke, and others, who have made connections between the two. The most obvious connection for me was that law prepared me as a researcher and that’s a skill that translates into creative and scholarly writing. Because I was a trial lawyer, I learned early how to take a lot of material (research) and craft it into a story for opening and closing arguments. But what I’m interested in now is experimenting more with how legal documents and texts can become part of a fictional work. If there’s such a thing as being turned out by a book, that book for me was Zong! by M. Nourbese Philip. In it, Philip uses a 1783 legal opinion concerning African slaves as cargo (Gregson v. Gilbert) as the basis for new lyric poetry. She just rends the opinion into its component letters and creates a new text intended to excavate the lost history of these enslaved and murdered Africans. It’s a stunning book that I’ve thought about quite a bit.

As far as the transition from attorney to writer to professor? It was an easy transition because I didn’t practice law for that many years. I knew in law school that I’d made a mistake. So, it was easy after practicing for a couple years to pursue writing because it had been what I always loved. Today, I’ve been a writer and professor much longer than I practiced law, but my family certainly had questions about what the hell I was doing with my life at the time that I made the transition. Let’s just say that leaving law wasn’t a popular decision.

+++

+