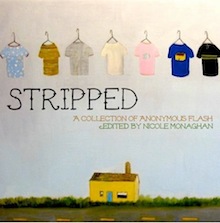

Recently published by PS Books, Stripped, A Collection Of Anonymous Flash (available in paperback and ebook) gathers stories by an impressive list of familiar and emerging writers — including a number of Necessary Fiction contributors — but leaves the bylines out of the book. A year after its release, on February 1, 2013, the author of each story will be revealed. In the meantime, the anthology raises some compelling questions about gender and writing, so we invited Stripped editor Nicole Monaghan to lead a discussion of those questions with some of the book’s contributors. And no, we don’t know who they are, either.

+

Nicole Monaghan: Roughly, what percentage of your work is written from the perspective of a character opposite your sex? Have you thought about the reason(s) for this breakdown?

Nicole Monaghan: Roughly, what percentage of your work is written from the perspective of a character opposite your sex? Have you thought about the reason(s) for this breakdown?

Participant 1: I’d say that about a third of my fiction is from the perspective of the opposite sex. I’m not sure why this is, but I’ve always written from the perspectives of both sexes. Even in high school, I’d write short stories from both perspectives without really thinking about it. Maybe the problem is that no one ever told me not to do it, so it doesn’t seem like a huge leap to me.

Participant 2: I had no idea what percentage of my work was written from the perspective of the opposite sex. I was really curious to take a closer look, and also found it was a little over a third of my work, almost a quarter. I make no conscious decision to say I am going to write from one side or the other, I just let the story and the voice decide. I have to admit I am surprised at how many of my character’s voices were opposite, but I think that reflects the kinds of stories I write. I like to experiment, hate having literary boundaries, so if I think a story is best told from another perspective, I’m going for it.

Participant 3: I’m a heterosexual male, yet over half of my pieces are written in a female voice. I think there are several reasons. One is that while in the corporate world, close to 80 percent of my co-workers were women. I’ve always felt more comfortable around women, safer, and for whatever reason I relate more to things that generally interest women — fashion, pop culture — than men.

The second — not to sound sexist — but it’s easier for me to make my characters vulnerable when they are women. It’s easier to make them ring true and honest, and personally, I find women more interesting because they are faced with far more challenges.

Participant 4: I’d say my work is about 50/50 in its gender breakdown. I think about gender roles a lot in my writing and in my life — and when I wrote academically I looked closely at male/female identification in film. I am able to better round characters if I’m mixing female and male traits within a person, and I would never consider just writing from one gender. Because, really, we all have gendered realities within us that match up both male and female at different times in our lives.

Just as I feel I need to understand and write from a variety of age groups, I need to slide around in gender too. It’s how I come to better understand humans.

I will say that when I write in first person — which is rare these days — I tend to write in my gender. Not sure why that is though. Now I feel the need to write a new story.

NM: When you write characters who are the opposite sex of your own, whether main or secondary ones, are you using less of “yourself” in the writing? Can you explain the specifics of how you render them? Observation? Research? How does it differ from creating characters of your own gender? Does it differ?

Participant 1: I don’t think it really differs at all. My biggest concern when I’m writing is creating characters who seem human. And to me, some of the most interesting things that make us human don’t have much to do with gender. We all have secrets. We all experience desire. We all want things we can’t have. And we’re all flawed in so many ways. The way gender comes into play for me has less to do with who I am and more to do with our culture. I’m especially interested in the kinds of messages our culture sends to both sexes. What it means to be a man. What it means to be a woman. Our culture places different sets of demands and expectations on members of each sex, and these are the factors I like to explore in my fiction. I don’t feel like I’m putting on airs when I write from the opposite gender’s point of view. Mainly I’m just asking myself how I would feel if culture placed X or Y expectations on me based solely on which chromosome my father gave me.

Participant 2: I agree with Participant #1 in that the reason these other-gender stories work is because our basic cores are simply human, and our basic needs are very similar. However, I do think there are other, more outward differences that I seek to capture. I think men and women sense things differently, take in information, gestures, sounds, smells, sights differently. I always try to put myself into the body and mind of my main character, and when writing about the opposite sex, use whatever knowledge I have of their way of thinking and processing and responding and try to capture that. We also have different speech patterns. So when writing dialogue, I work on recording those little nuances. It can be tricky, but I enjoy the challenge. And if I get it right, if readers buy it, then I have a greater sense of accomplishment with a story like that than I do with one told from my sex’s viewpoint.

And I want to mention one pet peeve, which I’m sure all writers have. It drives me crazy when readers get the sex wrong. I think sometimes this means I haven’t done my job and put in enough clues, but often it means readers have an innate prejudice toward reading a story with the assumption that it is in the point of view of the author’s sex. I hope we’re gradually moving away from that, and books like Stripped will surely help bring more attention to this issue, but it’s a natural instinct and I wonder if it will ever go away completely.

Participant 3: Most of my writing is about damaged people. They’re either wounded children or women. Much of my pieces have a large amount of autobiographical story in them, or at least a chunk of that essence. When I write about a child, I revert to being that child at that age. I feel their fears and have their hopes, and I am sitting right there with that child, crouched in the corner by the heat vent, praying for rescue.

Similarly, when I am a female narrator, I become my younger sisters, I become my wife, I become a female friend I know, a former coworker. For me it’s a bit like “method acting.” I also draw from that feminine side of me that all males have — some just being more open to exposing or cultivating it.

Participant 4: I tend to crawl inside my characters as I write. Suddenly I’m in there seeing the world from his/her eyes. I’ve always been a student of people — watching closely, eavesdropping, taking little notes — so all of that practice comes into play of course. But I guess I don’t consider too much that I’ve crossed into another gender. There are times when I’ll ask someone if dialogue seems accurate or gesture — is it too femmy? Too masculine for this character? I try to explain what I’m going for — but it’s more the psychology of the character than directly connected to gender. I mean — a woman can be very butch. A man can be very feminine. We’re a mix of these traits — the idea for me is for my reader to “see” my characters on the page — and then off it too. What I’m going for, overall, is a kind of honesty.

+++