Like many writers of a similar age and background, some of my most exciting memories of reading involve Choose Your Own Adventure books and playing/reading Interactive Fiction like Colossal Cave Adventure on my Commodore 64 (and, much later, discovering the more literary projects undertaken by Michael Joyce, Adam Cadre, Emily Short, Andrew Plotkin, and others. Lately I’ve had the pleasure of reading new works written and translated, respectively, by Mel Bosworth

and Matt Baker both of which feature interactivity and hypertextuality in the service of literary fiction. So I invited the two of them to have a conversation about their recent works and their writing in general, then got out of the way to let them talk.

+

Mel: Hey, Matt. Let’s begin by talking about The Numberless, a seemingly bottomless novel written by Jianyu Pên and translated by you. It’s being published online by the somewhat esoteric Beggar Press in an as-it-happens kind of way with fresh content appearing roughly once a week. And it’s going to continue until Pên’s death, or at least that’s the plan, yes? The whole concept is pretty mind blowing. I’ve got a million questions bubbling in my head already, but I’ll begin with just a few. What got you interested in doing work as a translator? How did you get involved with this particular project? Have you ever met Jianyu Pên, and if not do you ever plan to? What’s up with Beggar Press?

Mel: Hey, Matt. Let’s begin by talking about The Numberless, a seemingly bottomless novel written by Jianyu Pên and translated by you. It’s being published online by the somewhat esoteric Beggar Press in an as-it-happens kind of way with fresh content appearing roughly once a week. And it’s going to continue until Pên’s death, or at least that’s the plan, yes? The whole concept is pretty mind blowing. I’ve got a million questions bubbling in my head already, but I’ll begin with just a few. What got you interested in doing work as a translator? How did you get involved with this particular project? Have you ever met Jianyu Pên, and if not do you ever plan to? What’s up with Beggar Press?

Matt: I’d like to meet Pên, but I doubt Pên would agree to meeting. From the email exchanges we’ve had, Pên seems almost paranoidly obsessed with preserving her/his anonymity. So I don’t know anything about her/him, aside from that “Jianyu Pên” is a pseudonym: a year ago her/his pseudonym was “Ts’ui Pên,” but then she/he emailed me asking me to change “Ts’ui” to “Jianyu.” (Pên later explained she/he felt that “Ts’ui Pên… was just way too obviously a pseudonym!”) The senior intern at Beggar Press is “almost positive” that Pên is James Franco, but I really doubt that that’s the case.

But yes, Pên plans to add new pages to The Numberless once a week until Pên’s death, so it’s lucky that I’m so young, because Pên may need a translator for, who knows, forty, fifty, sixty more years? And the novel’s pages already number over a thousand. It’s an overwhelming project to be a part of. The translator fees Beggar Press pays me, however, make it all worthwhile. (I don’t have any idea where Beggar Press gets its money, considering that all of its publications are free to read. It has an office in Manhattan, an office in Nashville, and a building in downtown Reykjavík that’s downright palatial. Sometimes I worry the whole operation may be funded by organized crime — sort of a giving-back-to-the-community project, like that church that Los Zetas built in Mexico.)

Anyway, The Numberless is what Pên calls an “interlinked novel” — on each page of the novel, certain words/phrases/paragraphs are hyperlinked, and clicking one of those hyperlinked words/phrases/paragraphs takes you to the novel’s next (for you) page. That’s what I like about translating Pên’s work: all of her/his projects experiment with the internet as a medium. They exploit the internet’s storytelling capabilities — storytelling capabilities that print doesn’t have.

Or at least that I thought print doesn’t have. That’s what fascinates me about your novel Freight: it’s a print novel, but formally it’s what Pên would call “interlinked.” The Numberless takes the shape of a web (like the internet), but Freight’s shape is different. Did you experiment with other shapes? What was your process like, building such a formally complex novel?

Or at least that I thought print doesn’t have. That’s what fascinates me about your novel Freight: it’s a print novel, but formally it’s what Pên would call “interlinked.” The Numberless takes the shape of a web (like the internet), but Freight’s shape is different. Did you experiment with other shapes? What was your process like, building such a formally complex novel?

Mel: Matt, I think you have a ridiculously cool job with Beggar Press. Have you ever considered putting in a request to work at the Reykjavík office for a stretch? And wouldn’t you need an assistant with you then? Someone, oh I don’t know, a fellow writer to help keep you focused and productive, someone to bring you delicious coffee or something? Someone like me? Okay — me? I want to go with you to Reykjavík. Let’s make this happen, Matt. We can draft the request together. But anyway, I jest (not really).

So, I was fascinated with The Numberless before your response, and now I’m fascinated and also curious as all hell about the author, the publisher, the finer points of your involvement, etc. Ha. But to get back to the structure of The Numberless (I’ll catch up on your questions about Freight in just a second), which, as you mentioned, involves a hyperlink playground of sorts, I’m just…wowed, I suppose. It’s a blast to read, and, to be honest, I’ve only just scratched the surface of this thousand-page-and-growing internet tome. And yes, the internet has wild storytelling capabilities, for sure, and Pên (agreed — no way it’s Franco) has an amazing instinct on how to exploit them. In the past I’ve seen a bit of storytelling play on the internet, particularly with hyperlinks, and I think that’s what, in part, inspired the structure of Frieght, the idea that narratives don’t necessarily have to operate in a linear fashion. Which they often don’t anyway. I’m not sure we’re experiencing a new paradigm of storytelling here, though maybe we’re witnessing it from a different angle, and the internet has really helped to determine that angle.

I think the hyperlinks in The Numberless succeed because they offer humorous or informative asides, giving greater depth to major and minor characters. And they’re fun, and easy to navigate. I think the major difference between a work like The Numberless and my novel Freight is that Freight doesn’t offer any new information, per se, when you follow a “link” on the printed or digital page. Instead, the links in Freight connect events, or thoughts, from different periods in time. In this way, the link structure in Freight, as a whole, speaks more as a symbol of human memory and its non-linear nature. The overall process of forging the connections was pretty easy; it was the layout and formatting that posed the greatest challenge, I think. I should also mention that in the digital version of Freight (available on Nook, Kindle, and most e-readers. Ha!) the links actually act like hyperlinks so you can bounce back and forth if you so choose, whereas in the print edition you have to buzz through the pages like a deck of cards. But anyway.

Now you’ve got me thinking about the evolution of writing, Matt, in this digital age of ours where Generation Y aka Millennials scoff at printed books (do they scoff?) or reading lengthy, traditional narratives, or reading at all. How important is it, now and for the future, to tap into and adjust to the changing, shifting mindset of these damn kids? Is it necessary for authors to experiment with form at the risk of coming off as gimmicky?

Matt: Although I translate The Numberless’ new pages, I don’t publish them online — after I’ve translated them, I email them to Pên, and Pên herself/himself publishes them. So until new pages appear online, I never know exactly how Pên plans to “interlink” them, and it’s always fun for me to see how Pên has.

Anyway, I don’t know if it’s necessary for writers to experiment with form, but I’d prefer that writers did. And writers shouldn’t worry about “coming off as gimmicky.” (Some readers use “gimmicky” to mean “innovative,” the way some bloggers use “treehugger” to mean “activist” or some politicians use “terrorist” to mean “civilian.”)

I do think, however, that a story’s form should be tied to the content of the story — should be crucial to the telling of the story itself. Earlier this year I translated Pên’s Kaleidoscope (a “randomized novella”). The way that novella works is this: the novella has nine parts, which the website orders randomly — neither Pên nor the reader has any control over how the novella is ordered. And I’m sure some readers think that’s gimmicky. But if Kaleidoscope hadn’t been told in that form it would be a weaker story. It was given that form for a specific reason. Its form is crucial to its telling.

I do think, however, that a story’s form should be tied to the content of the story — should be crucial to the telling of the story itself. Earlier this year I translated Pên’s Kaleidoscope (a “randomized novella”). The way that novella works is this: the novella has nine parts, which the website orders randomly — neither Pên nor the reader has any control over how the novella is ordered. And I’m sure some readers think that’s gimmicky. But if Kaleidoscope hadn’t been told in that form it would be a weaker story. It was given that form for a specific reason. Its form is crucial to its telling.

I’ve also translated Pên’s Afterthought (a serialized novel). Although Afterthought’s pages already have been written/translated, the website won’t begin publishing them until after Pên is dead — Afterthought is “intended to be posthumous.” Again, maybe that’s gimmicky, but having read it I know that it’s crucial to the story that it be told in that posthumous form.

It seems to me that Freight’s “interlinked” form is at the very least relevant, if not crucial, to Freight’s content (the narrator is obsessed, for example, with ways of putting down/picking up experiences). But was that a worry with Freight? Before publishing it were you tempted to remove the links and publish it as a “traditional” novel? After publishing it did readers accuse it of being gimmicky? Don’t critics often seem lonely and underfed? (Pên’s told me that what she/he loves about writing The Numberless is that the novel has a sort of “immunity” to criticism — Pên doubts anyone has the patience/focus required to read the entirety of the novel, and can you ever accurately critique what you don’t fully understand?)

It seems to me that Freight’s “interlinked” form is at the very least relevant, if not crucial, to Freight’s content (the narrator is obsessed, for example, with ways of putting down/picking up experiences). But was that a worry with Freight? Before publishing it were you tempted to remove the links and publish it as a “traditional” novel? After publishing it did readers accuse it of being gimmicky? Don’t critics often seem lonely and underfed? (Pên’s told me that what she/he loves about writing The Numberless is that the novel has a sort of “immunity” to criticism — Pên doubts anyone has the patience/focus required to read the entirety of the novel, and can you ever accurately critique what you don’t fully understand?)

Mel: You’re right and you’re funny and you’re pretty awesome, Matt Baker. Freight’s form is relevant yes but it’s not crucial to its telling. But it adds a layer to the thing, I think, maybe two layers, three, four, five — who knows? Me, I guess. I was never worried about the whole “link” thing coming off as gimmicky, though maybe it did cross my mind a time or two that the book could survive without them. But I didn’t want it to. The whole “link” idea was there from the beginning, more or less, so I never had any plans on scrapping it. And I’m happy with the way it turned out. And I’ve been lucky so far in the sense that critics haven’t thrown any haymakers. Yet. But I’m sure someone will, sometime. And that’s fine. I don’t expect everyone who reads my book to do a goddamn back flip. Would be nice, though. Would be even nicer if they filmed themselves doing back flips and then posted them on Youtube. But anyway.

Critics are lonely and underfed a lot of the time, yes, you’re right. But they serve a purpose. And we’re all little critics whether silent or outspoken. And if our critics are right they keep us honest, if they’re wrong it’s all subjective anyway, and if they love our stuff then woo woo woo let’s throw a TV out the window to celebrate. We’re all a bunch of wildly insecure turds looking for heaps of praise or flat out silence. Because it’s scary out there, man. You know that. I know that, too. And Pên knows that. He/She has built a machine that is damn near immune to criticism because that machine has become so daunting to readers. And when Afterthought hits the interwebs he/she won’t be around to see any of the reader reaction at all. But what does that serve then? Art? The sheer craft of writing? Isn’t that kind of like “slipping the noose?” I often think of unread words as sticks of dynamite, and the eyes of readers as the flames that light the fuses. And it’s that reaction we crave, isn’t it? Seeing those lit fuses snap around? Which do you think is the better trade — executing a brilliant isolation from criticism or sitting back and watching bombs go off in human heads?

Matt: Personally I prefer watching the bombs. I can’t speak for Pên. Actually maybe I can. Here’s what’s just occurred to me: Pên may have designed The Numberless to have an “immunity” to criticism, but Pên does care, very much, I think, about the novel’s readers. For example — I’m the novel’s translator, but I’m also one of the novel’s readers, and a few months ago while reading the novel I found a contradiction. So I emailed Pên to alert her/him that I had found this “contradiction” within the story.

Pên never responded.

Instead, the very next day Pên emailed me a new page to be translated — a new page that resolved that contradiction. I don’t know if Pên always had been aware of the contradiction (had intentionally created it, intending to resolve it later elsewhere in the novel) or whether Pên resolved the contradiction solely because of my email. But, regardless, Pên resolved it.

The novel’s other readers sometimes email me about the same sort of thing — they’ll find an “error,” or an “inconsistency,” or a “contradiction” — and I’ll forward their emails to Pên. What’s curious is that Pên always resolves those problems by addition. Pên never revises by subtraction (the deletion of the “errors”) or substitution (the replacement of an “error” with something nonerroneous) — Pên always revises by adding new pages that somehow resolve those “errors.”

Anyway, Pên always responds to readers’ concerns (even if those concerns are simply questions about a certain character’s backstory or suggestions about a certain storyline’s setting), so in that sense the novel doesn’t have an immunity to critics — the novel and its critics actually have an interactive relationship.

(The novel is interactive in other ways, of course. Pên built a blog within the novel, for example, which includes a comments section: readers can post comments to the character’s blog entries, which comments then become part of the novel itself.)

Anyway, my own stories are far more traditional than Pên’s. But that’s part of the pleasure, for me, of translating Pên’s stories. At the very least, it’s something different.

Pên never tells me where her/his ideas come from, but maybe you’re more forthcoming. Do you remember where the idea for Frieght’s form came from? And once you had chosen the form for the novel, how did you choose the story to attach to that form? Or was it less intent, more instinct?

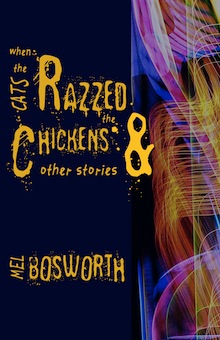

Mel: Freight came from the idea that I needed to relax when writing. When Folded Word — the publisher of my first fiction chapbook When the Cats Razzed the Chickens — asked whether I’d write their first novel for them, it kind of freaked me out and I put a crazy amount of pressure on myself because I’d never been offered something like before and I’ll probably never get offered something like that again. So for a few months I was just a nervous wreck sitting at my desk, and writing was slow and painful. I was terrified that I’d fail. I sent along an early portion of the draft I was working on for some feedback, and, while the folks at Folded Word had some good things to say about it, it occurred to me — perhaps because I’d given myself a little break, a moment to breathe — that I was beating the crap out of head. It occurred to me that this wasn’t the way I needed to write a novel. I needed to relax.

Mel: Freight came from the idea that I needed to relax when writing. When Folded Word — the publisher of my first fiction chapbook When the Cats Razzed the Chickens — asked whether I’d write their first novel for them, it kind of freaked me out and I put a crazy amount of pressure on myself because I’d never been offered something like before and I’ll probably never get offered something like that again. So for a few months I was just a nervous wreck sitting at my desk, and writing was slow and painful. I was terrified that I’d fail. I sent along an early portion of the draft I was working on for some feedback, and, while the folks at Folded Word had some good things to say about it, it occurred to me — perhaps because I’d given myself a little break, a moment to breathe — that I was beating the crap out of head. It occurred to me that this wasn’t the way I needed to write a novel. I needed to relax.

So I pulled back for a while and then approached it again with a new project in mind that centered around simple statements like “I ate” and “I lost” as the beginning of chapters. Soon enough, I had twelve such statements or prompts in total with each chapter having a kind of counterpoint to bounce off of. After I had everything in place, the machine kind of ran itself and I just had to keep pouring in the fuel. And while it was a more enjoyable experience than my first attempt, there was still a ton of work involved. But I had a better mindset, a better plan: get out of your own way. And it seems to me that Pên has really tapped into that mindset, too, by creating a writing experience that has lots of flexibility and room for reader inclusion. Damn, that dude really is something else.

And you’ve touched a great deal on the work of Pên and your intense and intensive involvement with that, but what’s next for your own work, your own writing? What does Matt Baker have up his sleeve these days?

Matt: I’m occasionally interviewing Michael Martone. I’m also writing a story about videogames and graffiti to add to my short story collection. I’m also revising a novel for children, rewriting a novel for young adults, and beginning to research for a novel for adults. I’m also writing and drawing my first comic.

I have a new writing process:

Don’t plan anything.

Invent everything spontaneously.

And when you catch yourself trying to plan things, anyway, secretly, despite those rules? Sabotage those plans as ruthlessly as possible.

(Another way of saying it — I’m writing with less intent, more instinct, lately.)

+++