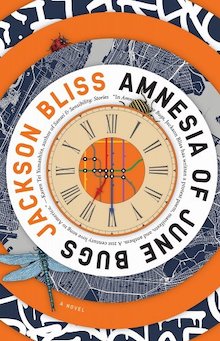

Our Research Notes series invites authors to describe their process for a recent book, with “research” defined as broadly as they like. This week, Jackson Bliss writes about Amnesia of June Bugs, published by 7.13 Books.

+

For Ten Years, This Novel was a Chunk of Starlight that I Buried In the Thick Earth & Then Dug Up Again, Heartbroken & Stubborn

1.

My research for Amnesia of June Bugs was pretty extensive in the beginning. That’s partially because I was writing about Chinese, Hong Kongese, and Taiwanese American characters and I didn’t know enough about their respective histories, cultures, languages, or cuisines to do them justice. So, I read a lot, but I also talked to people inside the diasporic communities I wanted to understand. I talked to my Asian American professor at Notre Dame from Hong Kong about Cantonese and Mandarin slang, I talked to desi classmates in my MFA program and my girlfriend in New York about Indian food, Indian history and geography, and Hindi grammar. I talked to PhD candidates in Chinese history and language. I talked to Moroccan American friends (and sometimes, complete strangers) about Moroccan Arabic (i.e., Darija) and local Moroccan cuisines. I traveled to Paris a bunch of times. I traveled to Casablanca and Marrakech. I lived in New York, Chicago, Seattle for many years, wandering the streets, people-watching at cafés, studying passengers on the subway, taking notes in my moleskine (and later my phone) for this ambitious and unruly novel.

My research for Amnesia of June Bugs was pretty extensive in the beginning. That’s partially because I was writing about Chinese, Hong Kongese, and Taiwanese American characters and I didn’t know enough about their respective histories, cultures, languages, or cuisines to do them justice. So, I read a lot, but I also talked to people inside the diasporic communities I wanted to understand. I talked to my Asian American professor at Notre Dame from Hong Kong about Cantonese and Mandarin slang, I talked to desi classmates in my MFA program and my girlfriend in New York about Indian food, Indian history and geography, and Hindi grammar. I talked to PhD candidates in Chinese history and language. I talked to Moroccan American friends (and sometimes, complete strangers) about Moroccan Arabic (i.e., Darija) and local Moroccan cuisines. I traveled to Paris a bunch of times. I traveled to Casablanca and Marrakech. I lived in New York, Chicago, Seattle for many years, wandering the streets, people-watching at cafés, studying passengers on the subway, taking notes in my moleskine (and later my phone) for this ambitious and unruly novel.

+

2.

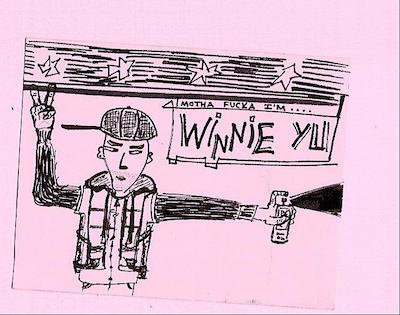

I also deep dived into the topic of culture jamming because it fascinated but also confused me. I had to learn graphie slang, the fundamentals of graffiti, the history of NYC graffiti, and some basic advertising concepts. I read Naomi Klein’s No Logo. I watched (and taught) Logorama. As with most novels, the majority of my research never ended up on the page, but I’d like to think that what did show up displayed an understanding of the conflicts that these characters were constantly navigating. Even after having written a shitload of drafts, I still asked friends and classmates who were part of these communities to read portions of Amnesia for feedback. I wanted my characters to have some level of complex authenticity. I supposed I wanted their three-dimensionality to be unimpeachable.

I also deep dived into the topic of culture jamming because it fascinated but also confused me. I had to learn graphie slang, the fundamentals of graffiti, the history of NYC graffiti, and some basic advertising concepts. I read Naomi Klein’s No Logo. I watched (and taught) Logorama. As with most novels, the majority of my research never ended up on the page, but I’d like to think that what did show up displayed an understanding of the conflicts that these characters were constantly navigating. Even after having written a shitload of drafts, I still asked friends and classmates who were part of these communities to read portions of Amnesia for feedback. I wanted my characters to have some level of complex authenticity. I supposed I wanted their three-dimensionality to be unimpeachable.

+

3.

One of the biggest mistakes I made with Amnesia of June Bugs was sending it to high-powered literary agents before it was ready. I was an editorial intern at the time at Warner Books and I worked with (and got along well with) the editors there, many of whom encouraged me to name drop them in my query letters, so I did because I was young and ambitious and impatient and full of hope for my nascent literary career. I immediately got the attention of several agents, even though I’d only written around a hundred pages of this novel. At the request of one famous agent in particular, who represented one of my favorite writers, I sent her the partial manuscript and then an outline of the rest of the novel along with five short stories at the advice of one senior editor. The outline was my second mistake. While some writers might benefit from working out their plot lines in advance and/or writing fiction with constraints as a way to create rules for their manuscript (something I’ve talked about with Aimee Bender, my thesis adviser at USC, many times), outlines are a death sentence to my fiction. Great for my critical essays, but fatal to my creative projects. Instead of letting this manuscript tell me where the plot lines were going, my plot structure was based on a hasty sketch I’d made to satisfy the curiosity of a literary agent who ended up rejecting me anyway after a year of agonizing radio silence and daydreaming. As a result, I sacrificed a lot of the organic unfolding of the novel and had to go back and rewrite the plot structure over and over again and rewrite the characterization as my characters started to reveal themselves to me more and more after each draft in direct proportion to the freedom I gave them. The other big mistake of mine was that I kept changing the rules of this novel: first, it took place in 2003 during the North American Blackout, then 2012 during Hurricane Sandy. First, there were six characters, then four. First the plot structure was linear, then retrogressive. First, the repeating metaphor was the void, then the four stages of the insect life cycle.

One of the biggest mistakes I made with Amnesia of June Bugs was sending it to high-powered literary agents before it was ready. I was an editorial intern at the time at Warner Books and I worked with (and got along well with) the editors there, many of whom encouraged me to name drop them in my query letters, so I did because I was young and ambitious and impatient and full of hope for my nascent literary career. I immediately got the attention of several agents, even though I’d only written around a hundred pages of this novel. At the request of one famous agent in particular, who represented one of my favorite writers, I sent her the partial manuscript and then an outline of the rest of the novel along with five short stories at the advice of one senior editor. The outline was my second mistake. While some writers might benefit from working out their plot lines in advance and/or writing fiction with constraints as a way to create rules for their manuscript (something I’ve talked about with Aimee Bender, my thesis adviser at USC, many times), outlines are a death sentence to my fiction. Great for my critical essays, but fatal to my creative projects. Instead of letting this manuscript tell me where the plot lines were going, my plot structure was based on a hasty sketch I’d made to satisfy the curiosity of a literary agent who ended up rejecting me anyway after a year of agonizing radio silence and daydreaming. As a result, I sacrificed a lot of the organic unfolding of the novel and had to go back and rewrite the plot structure over and over again and rewrite the characterization as my characters started to reveal themselves to me more and more after each draft in direct proportion to the freedom I gave them. The other big mistake of mine was that I kept changing the rules of this novel: first, it took place in 2003 during the North American Blackout, then 2012 during Hurricane Sandy. First, there were six characters, then four. First the plot structure was linear, then retrogressive. First, the repeating metaphor was the void, then the four stages of the insect life cycle.

+

4.

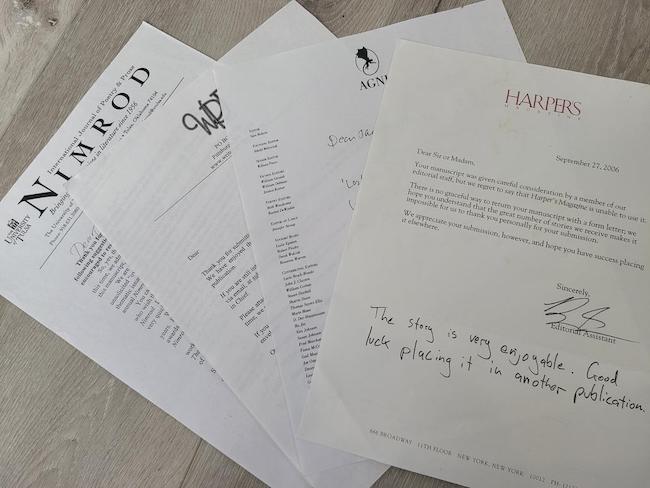

Some of the best rejections I kept (and one acceptance by a journal that went under two months after accepting a chapter from this novel)

This novel should be called The Book of Liminality because it’s been so close so many times to being accepted for publication, it’s almost criminal, but maybe that’s just my artistic ego speaking. After the drawn-out heartache of feeling so close to the writer’s dream and then returning to reality again, I felt like just another MFA student with a desultory imagination and talent to burn. At least I had lots of New York stories to bring back with me to South Bend, along with some dope clothes, a bunch of books from Warner Books’ take shelf, and a Canadian stamp in my passport. During the second year of my MFA back in the Midwest, I worked furiously on Amnesia of June Bugs, writing between three and eight hours every day. Whenever I had a spare moment. At night. Every weekend. During off hours in the creative writing office. I finished my first complete draft shortly before graduation (all four hundred and fifty pages of it) when I learned that I’d won the Sparks Prize, an award given annually to one graduating MFA student in my program. This was my first taste of the writer’s life. In the next five years, literary agents contacted me after reading self-contained chapters in ZYZZYVA, Antioch Review, and Fiction. I sent out hundreds of query letters every year like love letters to the void. Some agents ignored me, most sent form rejections, a handful emailed me generous, thoughtful, and supportive rejections. Some even included constructive criticism, which I knew took time. I saved every kind word, storing them in a blue plastic folder that I still have to this day. In their rejection letters, agents spoke in the language of infatuation, relationships, and corporate hiring practices:

- I admire you an artist but I’m not in love with your art.

- Your book isn’t the right fit for us right now.

- It’s me, it’s not you.

- We received a number of truly qualified

applicants’manuscripts. - It’s a deeply subjective process.

- I wish you the best of luck in your future endeavors.

- This decision is not a reflection of the literary merit of your manuscript.

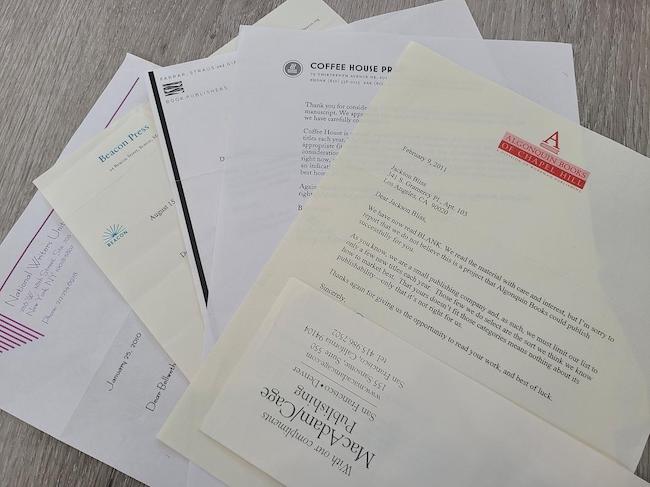

In time, these rejections became easier to accept and easier to dismiss and harder to understand. I submitted Amnesia of June Bugs to small presses and book contests like the Bellwether Prize. After receiving kind rejections from Coffee House Press, Greywolf, Algonquin, MacAdam/Cage, Beacon, and Soho Press, I moved to Buenos Aires with my then-girlfriend and revised Amnesia in my spare time when I wasn’t teaching English to Argentine IT employees who liked to make lewd jokes during lessons and watch futból games on their laptops while scarfing down empanadas.

A few of the rejection letters I’d saved from small presses

+

5.

Several years into my PhD at USC, I submitted Amnesia of June Bugs to Kaya Press, which had moved from NYC to USC’s main campus coincidentally. I figured that being the only AAPI small press in the mainland made it a good match. After the board wrote a supportive rejection letter, offering to read a major rewrite, I worked with Kaya’s brilliant publisher, Sunyoung Lee, for two years on this novel. With her enlightened guidance, I slowly transformed Amnesia into the novel I knew it could be. The novel became simpler. The characters became more complicated. The plot structure became layered and complex. I methodically addressed each issue and concern the board had mentioned in its rejection letter with Sunyoung’s help. Once we both felt good about the manuscript, we re-submitted it. The board rejected it again. Something died inside me that day. I gave up on this novel for the longest time. I figured that if an experimental AAPI press didn’t want an experimental AAPI novel, then no one would. For years, I couldn’t bear to look at this book without feeling a piercing pain in my ribcage and okay, a little rage too.

+

6.

To get over my heartache, I worked on other novels and other genres. I started my memoir Dream Pop Origami, revising it during my commute from LA to Irvine. I revised and reconceptualized my debut short story collection, Counterfactual Love Stories & Other Experiments. I sought and found refuge in other manuscripts. Eventually, though, I always came back to Amnesia. Some part of me couldn’t let go. I couldn’t abandon these characters or the novel’s endless potential. I cared too much about this book. I could see the movie inside my head when I read it. And the latent Shintoist in me felt like this novel had a soul, so I ended up working on this novel. After reading Leland’s mission statement on the 7.13 Books website, I submitted Amnesia during one of the low points in my life and then forgot about it. Once I’d returned to the Midwest with a tenure track job, I found a home for Amnesia of June Bugs. I can’t help but feel like it’s not a coincidence that the two editors of 7.13 Books are both AAPI prose writers themselves. I can’t help but feel like it’s kismet that my debut novel and my first tenure track job are interconnected somehow.

+

7.

When I tell my MFA students that it took me fifteen years to revise, rework, and rewrite Amnesia of June Bugs, which was my MFA thesis, and turn it into a publishable manuscript, they look at me in straight-up horror, disbelief, and judgment like I just admitted to shooting up with a dirty syringe that I’d stolen from my diabetic obāchan. The truth is, it took me so long because I didn’t know what the fuck I was doing for much of the first draft because so much of your first novel draft is simply teaching yourself how to write a novel. Before it’s a book, it’s a heuristic.

+

8.

The first thing I had to do in order to write Amnesia of June Bugs was teach myself how to stop writing short stories, which is fucking hard since that’s what we’re groomed for since workshops are designed for short stories. They’re easier to workshop since they don’t require context, plot summaries, or macrostructure and publishing them in prestigious literary journals used to be one of the best ways to find a literary agent. Now, tell a prospective agent about your dope short story collection and they get a glazed look in their eyes like you’re trying to get them to invest in a pyramid scheme, which might not be the worst analogy of corporate publishing. You can practically count the seconds until they ask you if you’ve got a novel to go with that pipedream. Little do they know that this novel is the pipe dream.

+

9.

The second thing I had to do was a shitload of research before I felt like I could write the things that I wanted to write in order to say the things I needed to say. I had to learn about political graffiti, Chinese history, verlan, Indian cities, Cantonese slang, Moroccan geography, and also refresh my memory on ‘90s pop culture. I consulted a number of BIPOC friends, mentors, and fellow writers and asked them endless questions. Several desi friends helped me out with Hindi. I also re-read old journal entries of mine from my time in Burkina Faso, Seattle, Portland, Istanbul, Chicago, and NYC. For years, I carried around a dog-eared NFT New York with me whenever I went to cafés in case I needed to consult it while making revisions. I even cold called a few New York city cafés mentioned in this novel to make sure I got some of the historical details correct.

+

10.

One reason it took me much longer than normal to revise Amnesia of June Bugs is because I had to rescue it from the dungeon of corporate respectability. When my novel was under consideration by a top literary agency, I made the mistake of writing to get published instead of writing to tell my story. I made editorial decisions — consciously and unconsciously — that were designed to maximize my novel’s marketability, increase its appeal to the NYC literary establishment, and get my foot inside the citadel of Big-5 imprints. Once I set my novel free, I went back to basics and rediscovered my elemental love of language, characterization, structure, and narrative. I revised this novel until I could find myself in it again, which took time because I’d been lost for such a very long time. My writing is slangy, musical, lyrical, and a bit explosive on the page. But turning a phrase takes so much time and there are lines in this novel I rewrote several hundred times. I don’t need readers to know how much toil went into the writing of this book, how many conversations I had with these characters inside my head, how often their lives kept me up at night and how much their humanity became a project I vowed to understand, protect, and defend to the very end. But I do want readers to feel as if Amnesia of June Bugs is a home for them where they can find refuge. At the end of the day, I believe that we all have the right to be heartbroken about the world we live and also have the right to be in love with the stars in the sky whose songs will never reach us until we are all stars ourselves. I’d like to believe that this novel is someplace between the star and the sky and the song.

+++