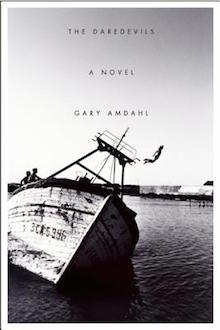

Our Research Notes series invites authors to describe their process for a recent book, with “research” defined as broadly as they like. This week, Gary Amdahl writes about The Daredevils from Soft Skull.

+

Records of the earliest work on The Daredevils can be found at two sites, one in Minneapolis, one in Saint Paul, dated 1984 and 1988. A story called “The Cyclist” is sketched out in the earlier document, sheets from a yellow legal pad, with references to American Racer: 1900-1939, and Living My Life, by Emma Goldman. The author knew a great deal about motorcycle-racing, having done some himself, but little about big board-track racing, a front-of-the-sporting-pages phenomenon of the 1910s, and knew of Goldman only as “an anarchist” somehow connected to the McKinley assassination. “The Cyclist” was about a velodrome bicycle racer in Philadelphia who was beginning to race motorcycles at the same time he was involved in efforts to unionize the bicycle manufacturing shop where he worked.

Records of the earliest work on The Daredevils can be found at two sites, one in Minneapolis, one in Saint Paul, dated 1984 and 1988. A story called “The Cyclist” is sketched out in the earlier document, sheets from a yellow legal pad, with references to American Racer: 1900-1939, and Living My Life, by Emma Goldman. The author knew a great deal about motorcycle-racing, having done some himself, but little about big board-track racing, a front-of-the-sporting-pages phenomenon of the 1910s, and knew of Goldman only as “an anarchist” somehow connected to the McKinley assassination. “The Cyclist” was about a velodrome bicycle racer in Philadelphia who was beginning to race motorcycles at the same time he was involved in efforts to unionize the bicycle manufacturing shop where he worked.

By 1988, a second yellow pad refers to a full draft of a novel called The Daredevils, set in San Francisco in 1916, the story still concerned with radical labor and motorcycle racing but now revolving around anarchist Alexander Berkman and his newspaper The Blast. Berkman, Goldman, Teddy Roosevelt, and other historical figures are now characters in the novel. The books referred to are Goldman’s Anarchism and Other Essays, Berkman’s Prison Memoirs of an Anarchist, Paul Avrich’s Anarchist Portraits, and George Woodcock’s Anarchism: a History of Libertarian Ideas and Movements. All of them appear to have been the property of the Saint Paul Public Library. A list of publishers to whom the novel was sent has also been found.

The next site of archeological importance is in Willimantic, Connecticut. Six “blue books,” of the kind used for school examinations, dating from 1992 to 1997, are filled to the point of illegibility, front cover to back, in black, blue, red, green ink, and pencil, with Dewey Decimal System numbers retrieved from card catalogues at the University of Connecticut, quotes from books, passages from the novel, phone numbers, and, tucked between two pages, a Polaroid snapshot of the library wrapped up in what appears to be a large plastic bag. (The library was being remodeled, and the construction was apparently being managed by the mob. Big chunks were falling off, and scholars were urged to approach the building with caution.) An agreement was drawn up between the author and a literary agent. A small, blue, spiral-bound notebook lists meetings with editors in New York.

Activity at the Willimantic site can be characterized in three ways:

- by the astonishing number of books read;

- by an addition to the novel of what amounts to “a second half,” set in Minnesota in 1917; and

- by the destruction, in a fit of angry despair, of all the author’s fiction manuscripts, including two other novels, Getting the Hell Out of Dodge and Dead Hand. (Part of the former had been produced as a play in Saint Paul in 1989, and part of the latter had been published in Fiction and read at City College in New York in 1992.) Ash deposits and bits of burnt foolscap with key words still legible are all that remain.

A selection from the bibliography includes: Wallace Stegner’s Joe Hill; Henry James’s The Princess Casamassima; William Godwin’s Caleb Williams and Enquiry Concerning Political Justice; William Morris’s Erewhon; Thomas More’s Utopia; Anarchism: a Documentary History of Libertarian Ideas, Volume One: from Anarchy to Anarchism (300 CE to 1939), edited by Robert Graham; Buhle, Buhle, and Kaye’s The American Radical; Errico Malatesta: His Life and Ideas, compiled and edited by Vernon Richards; Kropotkin’s The Conquest of Bread, The State: Its Historic Role, and Fugitive Writings; Woodcock’s biography of Proudhon and Proudhon’s What Is Property?; Bakunin’s Statism and Anarchy; Arnold’s Culture and Anarchy; Lewis Mumford’s The Story of Utopias; Alice Felt Tyler’s Freedom’s Ferment; and, last and greatest, Dostoevsky’s The Possessed (Demons as it now more correctly translated) and the dramatization of that novel by Albert Camus.

The last site of significance in the development of “Daredevils Culture” is in Southern California, at Redlands, with deposits dating from 2004 to 2014. Journal entries show the author lamenting the loss of the manuscripts, but determined to start afresh, feeling that he could remember nearly every word he had written anyway, that they were “burned in his skull.”

In 2005, an extraordinary find was made at a site not far from the Willimantic dig, about halfway between that site and the campus of the University of Connecticut, in Mansfield. The author’s wife, who was teaching at the University of Redlands, received a call from her friend and former thesis advisor at UConn, saying that she had come across a copy of The Daredevils in a pile of papers at the back of a closet. Oral history accounts suggest that the author had threatened to destroy the manuscripts before actually doing so, and that his wife had made a copy, given it to her friend, and forgotten about it over the course of the next very busy not-quite-decade.

The novel, meanwhile, had undergone major changes. A wealthy young man who had witnessed the destruction of San Francisco in 1906, and whose father was a crusading anti-graft prosecutor and re-builder of the city are now the center of a story that has more to do with realism and reality than anarchism and polity. Revisions show a deepening understanding of the hypocrisy and criminality of the do-gooders, and a stunningly corrupt judiciary. The books that stand out here are: Imperial San Francisco: Urban Power, Earthly Ruin, by Gray Brechin; Boss Ruef’s San Francisco, by Walton Bean; The Great Earthquake and Firestorms of 1906: How San Francisco Nearly Destroyed Itself, by Philip Fradkin; The Regenerators: A Study of the Graft Prosecution of San Francisco, by Theodore Bonnet; and Richard Frost’s The Mooney Case. A backstory with its origins in the time in Willimantic began to grow with the help of Anne Tripp’s The I.W.W. and the Paterson Silk Strike of 1913. A wider sense of national politics was provided by Marguerite Young’s Harp Song for a Radical and James Chace’s 1912: Wilson, Roosevelt, Taft and Debs: The Election that Changed the Country.

The artificial reality of the stage (and more generally of all art), where the wealthy young main character has chosen to spend all his money, begins to steer the last revisions away from what is toward what is not. The central image—the “disappearance” of the Golden City—becomes theatricalized trauma as the son plays over and over again the father’s Stoic admonitions that “nothing unreal is allowed to survive,” and “nothing has been lost here that cannot be swiftly and easily replaced.” Writings on realism and naturalism by Zola (“Preface to Thérèse Raquin” and “Naturalism in the Theatre”), Andre Antoine (Le Théâtre Libre), David Belasco (“Acting as a Science”), Strindberg (“Preface to Miss Julie”), and Stanislavski (An Actor Prepares, Building a Character, Creating a Role) are all re-read. (The author spent most of the 80s in the theater.) Martin Green’s New York 1913: The Armory Show and the Paterson Strike Pageant was easily one of the most important books the author read during the thirty years of the novel’s development. The chapter on realism in 19th C France, in Arnold Hauser’s The Social History of Art, Volume Four, seems, in retrospect, equally fundamental—that is to say, structurally fundamental, as opposed to the hundreds of pages of load-bearing details provided almost novelistically in Green’s book.

There is only one more category of research, and only four books in it: Poliltical Prairie Fire: The Non-Partisan League 1915-1922, by Robert Morlan; Watchdogs of Loyalty: The Minnesota Commission of Public Safety in World War I, and The Progressive Era in Minnesota, 1899-1918, by Carl Chrislock; and Minnesota Farmer-Laborism: The Third Party Alternative, by Millard Gieske. These books not only informed the last revisions of the novel, they changed what the author thought he knew about the social and political life of the state he had been born in. His parents had both grown up on up on small (160 arable acres each, approximately) polyculture farms, one in Jackson, MN (where the author was born, in a farmhouse with no indoor plumbing), the other in Ossian, Iowa, and the author was inclined to see farmers as Romantic Jeffersonian Yeomen. A locally produced movie about the Non-Partisan League, Northern Lights (1979), which won an award at the Cannes Festival, deepened that belief. But it was closer to the truth to say that there had never really been such a thing as a Jeffersonian Yeoman Farmer, and that the Non-Partisan League had not sprung up from the North Dakota and Minnesota soil, as it were, the simple product of simple men standing up to the mighty railroads and Big Grain, but rather as the product of small businessmen leaning sharply but carefully toward socialism. That there was a socialism to be leaned toward was news to the author as well: when he learned that a mayor of Minneapolis had been a candidate of the Socialist Party (Thomas Van Lear, 1917-1919), it seemed to alter the very character of the city.

Those socialists, along with labor unions, immigrants, advocates of free speech and a free press and birth control, and any group or person opposed to the war, were branded by the Minnesota Commission of Public Safety as disloyal, and brutally repressed. The Japanese-American internment camps of WWII and campaign promises of the 2016 Republican presidential candidates are the only examples of similar repression that spring quickly to mind. The story of the MCPS, as told by Chrislock in Watchdogs of Loyalty, is probably the one book The Daredevils could not have been written without.

+++