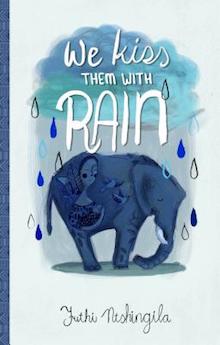

Catalyst Press, 2018

I was a teenager in the late 80’s and early 90’s, when AIDS became a prominent part of the American news cycle. I remember the panic and fear. The campaigns on television and the assemblies in high school simultaneously promoting abstinence and condom use. Rampant misinformation, fueled by prejudice and wild rumors, filled the vacuum created by the absence of a cure.

These days no one talks about AIDS, at least, not with the same urgency as we talked about it back then. It is one of those diseases that is forever connected in the American psyche to a specific period, – like polio, smallpox and Spanish Influenza. The ability to relegate what was once a matter of life and death to history is an unacknowledged luxury of the West.

I was reminded of this as I read the South African writer Futhi Nthshingila’s second novel and North American debut, We Kiss Them With Rain _(originally published under the title _Do Not Go Gently). In the foreword Ntshingila explains that she was inspired by the story of a local man who, dying of AIDS, joked that he wanted the women he’d known to attend his funeral without panties. After hearing this, Ntshingila “sat down and wrote an unreal story of a man who was so loved by his women that, even after infecting them with HIV, they still worshipped the ground he walked on.” It was the kind of love and loyalty she found difficult to understand, but which she had witnessed more than once. “I don’t know what it all means to feminists, conservatives, moralists or whoever else,” she continues, “but I know that when I wrote his story, I learnt and felt something about love that is unconditional but dangerous too.”

And so she created Sipho, a problematic man who unabashedly enjoys women. Financially well off, kind and charming, successful and attentive, it’s easy to see why they are drawn to him. But We Kiss Them With Rain is only tangentially Sipho’s story. It is Ntshingila’s female characters, — Zola, Mvelo, and Nonceba — who steal the limelight and are the true heroines of her novel.

Zola is a single mother who supports both herself and her daughter, Mvelo, by working in her Aunt Skwiza’s shebeen (bar). There she meets Sipho. She is initially suspicious of his attentions, but begrudgingly allows him to earn his way into her heart. After months of courtship she moves into his home. Sipho acts as a surrogate father to Mvelo, for whom he holds a strong and sincere affection. They become a family. But when the beautiful and intelligent Nonceba enters his life, Sipho tells Zola that this new woman is what his heart wants. And so, much to his surprise, Zola leaves rather than share him. She moves herself and Mvelo to the shacks, where the very poor live on the edges of the city of Durban.

Zola’s stay with Skwiza wasn’t long. She worked fast with some of Skwiza’s patrons who had found space and material to build a shack for her in a mushrooming shack town on the margins of uMkhumbane. She was hurt, and afraid for her daughter. Stories of child rape spurred her on to work fast to get Mvelo out of the shebeen and harm’s way. Zola was quiet by nature, but now, in her private pain, her silence was loaded with fear and rage and disappointment. It was so deep that she couldn’t bring herself to feel it. She just focussed on making a home for Mvelo. She began to look for work and sold second-hand clothes in town.

Ntshingila is quick to point out that, despite her role in this break-up, Nonceba is not a villain. Sipho has misrepresented his relationship to Zola. Nonceba believes that this woman is the live-in housekeeper, a loyal domestic whose daughter Sipho has grown attached to. And while Zola’s pride will not allow her to share this man (and risk contracting HIV) she does not stop caring for him. Nor does she waste time being vindictive. Zola is practical. She allows Sipho and Mvelo to continue their father-daughter relationship. She does not stop Nonceba from acting as a stepmother to Mvelo and taking an active role in directing the girl’s education. It is interesting that though Zola and Nonceba never directly interact with each other on the page, they are connected by their love for both Sipho and Mvelo. And from that love is born respect and a shared purpose. It is not sisterhood, or friendship, but it is something.

Even with this strong support system and the love of so many people, 14-year old Mvelo’s journey is a difficult one. And it is Mvelo’s journey that this novel is, ultimately, about. Beginning with Zola’s funeral, Ntshingila proceeds to tell their story through flashbacks. Answering the question of how Zola came to die of a cruel disease made manageable through medications. From 1999 to 2008 the South African government of President Thabo Mbeko denied there was a correlation between HIV and AIDS, despite all the scientific evidence. Largely because of the resulting misguided policies that country has the highest HIV epidemic in the world, with women making up the majority of the sick. The hardships and pain Mvelo and her mother suffer are all too common for woman of their race and economic status in South Africa.

Nonceba, in contrast, is bi-racial, educated and a member of a privileged elite who were raised overseas and returned with dreams of building a new South Africa. But Noceba has spent more time living outside of her country than in it, which explains her sense of guilt. She never knew her white, Afrikaans father – who abandoned her mother rather than admit to having an interracial relationship to his family. Despite her attachment to both Sipho and Mvelo, Nonceba still struggles to find a place for herself in the world.

We Kiss Them With Rain is a social novel, more in line with the works of twentieth century writers like Upton Sinclair, John Steinbeck and Richard Wright, than crusaders of the modern era. Like those earlier works, it is written with a dual purpose – to both entertain and inform – and relies on a series of somewhat far-fetched coincidences to resolve major plot points. The tone can be, at times, earnest, but that earnestness is in service to highlighting institutional poverty, social inequality, victimization, and sexual assault. The virus is a palpable presence (the text is seeded with acronyms – HIV, AIDS and ARVs) and exists in the same room as the characters, like furniture. For Mvelo, who watches both Zola and Sipho die of AIDS, it is an obsession.

It was that day, when her mother’s disability grant was discontinued, that Mvelo stopped thinking any further than the day ahead. At fourteen, the girl who loved singing and laughing stopped seeing color in the world. It became dull and grey to her. She had to think like an adult to keep her mother alive. She was ina very dark place. One day she woke up and decided that school was not for her. What was the point? Once they discovered that her mother couldn’t pay, they would have to chuck her out anyway.

The book works is because the prose style is kept simple, written at a young adult level. The characters are frequently awkward, as in the scene where Mvelo’s friend and neighbor attempts to read a Dylan Thomas poem over Zola’s grave and what is meant to be a poignant tribute becomes a belabored, if sincere, performance. And yet, that awkwardness covers the entire project with an unexpected blanket of authenticity. We Kiss Them With Rain is narrated in the third person, but the lack of polish on the final text makes it easy to imagine fictional Mvelo being its actual/model author, writing her own story as if it belonged to someone else’s. Little life lessons are sprinkled throughout, which create a nice balance between the instructional (characters are constantly visiting the clinic to be tested for HIV) with the aspirational happy ending. And still, Ntshingila manages to charm us, eventually presenting us with an ending which, although abrupt, has an almost Dickensian feel to it. An ending which encourages in us the childlike hope that her characters – specifically Mvelo, one of the many orphans left alone in the wake of a terrible disease – will find happiness if only she follows the correct path. Not because is guaranteed to work out in the end, but because she is given the gift of a future.

+++

+