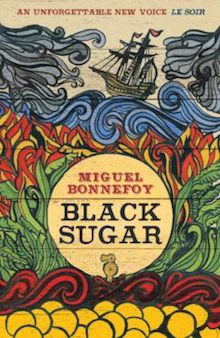

Gallic Books, 2018

The opening image of Miguel Bonnefoy’s Black Sugar — a pirate ship marooned in the canopy of a rainforest — invites the suspension of disbelief necessary to fully appreciating the rest of the book.

Black Sugar is best described as an exemplar of magical realism told so confidently that it could almost be true. With his second novel, Bonnefoy has mythologized the creation of Captain Morgan rum, spinning a tall tale that also encompasses three generations of a family’s history, and the industrialization of Venezuela. While those are broad demands, Bonnefoy keeps the narrative tightly focused on his characters, and the novel neither rushes nor drags.

Instead, the story is told as though it’s a village legend, and the reader is being let in on the secret. Bonnefoy jumps in time and plays the voice of God on more than one occasion, underscoring the idea that this is a narration. His language, too, is descriptive — begging to be read aloud. For English readers, the beauty of the words is not lost in Emily Boyce’s translation. An early sentence reads:

The first mate lit a candle, illuminating the captain’s face with its French-style moustache, long hair caked with grease and hemp, and eyes bloodshot from forty years of piracy. The flame reddened his teeth and tinged his skin yellow. Mauve shadows gnawed away at his cheekbones.

Bonnefoy underscores his mythmaking by centering the narrative on two archetypal characters. Severo Bracamonte is a classic adventurer, driven by greed. He comes to Venezuela seeking the treasure that was aboard Henry Morgan’s tree-bound pirate ship. Upon his arrival, he stays with the Otero family, including daughter Serena, a longing young woman looking for passion.

But Bonnefoy challenges the most obvious route for these characters. Severo is not successful in his endeavors, and Serena never morphs into a docile, young bride. Though they settle into what Bonnefoy calls a “state of surrender,” Serena in particular retains a deep dissatisfaction with her life. She is bright, well-read and curious about the world — though her character development is hampered a bit by the tell-don’t-show momentum of the book. Still, she is a confident and capable character who still retains a sense of traditional femininity. Her arc is both realistic and refreshing.

Severo and Serena are also used to represent industrialization and Venezuela, respectively. The former marches into the quiet village in the first portion of the book, bringing with him tools to tear up the countryside in search of treasure. He says, “People bury treasure in land that will never change.” It’s foreshadowing, for the fact of his presence is already evidence of change, and a catalyst for more.

In one of his first interactions with Serena, Severo is ready to dig up a fragile tree in the forest, arguing that they could “plant a thousand trees with what we find underneath this one.”

But Serena, lover of nature and protector of the land, stops him:

She took a few steps forward to touch the bark before turning to stand between Severo and the trunk, as if protecting a child.

‘If you uproot this tree,’ she said, placing a finger over her heart, ‘let your pickaxe strike here first.’

From the very beginning, the central concern of this novel is finding this lost treasure. The reveal of where it lies is too good to spoil, but it makes the reader flip back through the book to look for the clues Bonnefoy hides throughout. Greed begets greed, and the treasure is used as fuel for further industrialization and war profiteering, but is also poured into a rum-making business, resulting in the legend of the rum named for Captain Morgan.

Bonnefoy quickly and harshly punishes the avarice of his characters. First, Morgan dies a wretch among mutineers and a crumbling ship. Then Severo, Morgan’s spiritual descendant, dies a similar extended death as the old pirate: their bodies corrupting in shades of blue and green as they obsess over treasure. Only Serena is really spared, as she is the character least interested in wealth.

Serena and Severo’s daughter, Eva Fuego, becomes the primary protagonist of the last portion of the novel. She is found in a patch of fire-scorched earth, as if she is the treasure her father has been seeking all along. She grows up strong, willful and physically sturdy, working with the land to turn her family’s small rum operation into an empire. She is another well-developed female character, like her mother, but with an ambitious streak like her father. Bonnefoy describes her:

By the age of seventeen, she had become what she would remain all her life: a woman whose existence would find meaning only in the pursuit of a pipe dream. […] The peace and quiet of the forest did little to calm her; on the contrary, it taught her that anything could be made to submit.

Perhaps part of the reason Bonnefoy grants Eva success where her parents stalled is that she is a true villager. Her parents, on the other hand, prefer colonial trappings: Severo erects a statue of Diana in front of the home, while Serena swoons over European authors. It’s no small detail that Eva, the girl literally born of the soil, is the most able to bring wealth to the village.

But Eva, too, exceeds the limits of her allowed prosperity when she begins importing foreign goods to her estate to put on an ostentatious display of her power. The outcome completes the story’s moral on the dangers of greed.

Eva and Serena provide a powerful endnote to the book. The moving scene between mother and daughter reaffirms all that is good — love, family, loyalty — and damns the treasure that started the novel once and for all.

Black Sugar comes out at a time when Venezuela is in the news for violence and turmoil. But Bonnefoy’s prose bursts with pride for the region and its people, particularly the farms and farmers. At the same time, he acknowledges the colonizing forces that fomented unrest, whose influence is felt today as the country destabilizes. It’s an important book to read right now, for even though it’s fantastical fiction, it gives the reader context for the next headline.

+++

+

+