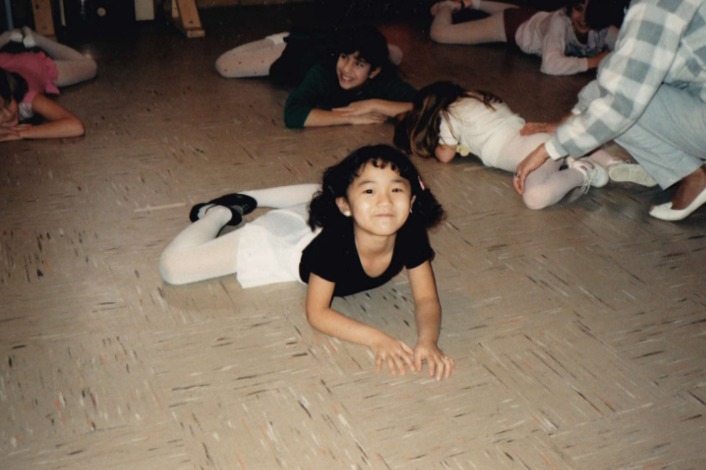

My mother hands me two brochures: one for ballet and one for gymnastics. I don’t speak English—I am still new to America—but I understand enough to know that I am to choose.

I choose tutus.

+

Thirty years later, I find myself in a PhD program for creative writing. I ask myself frequently, “What am I doing here?”

Over the phone, my mother feeds me my own answers from during the application process: “Experiencing a new part of the country. Preparing for the job market. Reading. Writing another book.”

I hang up the phone and cradle myself. I rock back and forth and sob. My head hurts. My eyes hurt. I hate reading. It’s like having my eyelids flicked every time I shift to a new line. Holding the lines in place without having them swim around the page—something I can do now after two years of rehab—uses the same muscles it takes to cross your eyes and stare at the tip of your nose. For hours.

The question persists: But why?

+

I pick myself up and put on my running shoes. There’s a five-mile loop I do, not just for the endorphins but because it numbs me to a point where I can’t think anymore, and it’s wonderful. To be so much at peace.

But my hamstrings are tight. My legs are getting squatty.

So I confess: I return to ballet out of vanity. The desire to be long and lean. But quickly I realize other reasons. A desire to express myself without words, without paper. Desire to find a new way to tell stories, without reading, without writing. Desire to be a body in a body of moving bodies. Desire to control the movements of my body, which has been unpredictable and unreliable for two years now. Desire to become a swan, a princess, or even just a toadstool. To be inside the stories I’ve loved all my life. To be a character in a fairy tale.

+

Princess Odette is transformed into a swan by an evil sorcerer. Her home is the lake formed by her mother’s tears. The magic and tragedy of this.

My instructor places her hands on my shoulder blades: “Shoulders down, neck elongated. Push your shoulder blades back and together. In Swan Lake, a ballerina’s arms are held behind the rib cage. Don’t let go. Hold it. Hold it.”

+

Daily, with something so simple as sustaining proper posture—the position and carriage of the body—ballet re-instills in me self-discipline and self-respect, for my body, my back, my rib cage, my neck, my shoulders, my core, my life. I stand tall, perfectly aligned. I hold myself up and stand proud, like I am someone, like I belong here, like I can do anything—including remember simple barre and centre combinations, or read three hundred pages of Bleak House a week and finish this paper about Dickens’s belief in the power of fairy tales to save children.

+

My instructor pricks her finger on Sleeping Beauty’s spindle and her arm flies into the air, swoops into a high, wide arc, before she cradles her hand against her heart, her chest open and exposed to the audience. “From a bird’s eye view above the stage, you will never see a ballerina hunched over, you will never see her shoulder blades or the back of her neck. Outside of class, everywhere you go, respect this tradition. Maintain upright carriage.”

+

When I read, when I write, when I sit in class, when I drive home, when I shop for groceries, I maintain my upright carriage. Shoulders down, neck long and high. I reach and stretch from the top of my head to the tips of my fingers and all the way down to the ends of my toes.

I am Sleeping Beauty, waking up.

I am Odette, transformed.

And Cinderella, sweeping the house, washing dishes, taking out the trash.

+

I’m only a month in at three classes a week, but ballet has saved me.

It has saved me in a way that rehab and running and meditation and rest have not. It has returned me to myself, my child self, my self before my brain injury.

+

During strength and conditioning, my instructor rises onto demi pointe with her supporting leg and lifts her working leg into the attitude position. Or maybe she is in arabesque and en pointe, demonstrating cambre back. I get lost in her demonstrations, trying to memorize the positions. Meanwhile, she is all grace and poise. She is inspiration on two perfect feet. But from within this moment of beauty, she lets out a series of grunts and then a barbaric roar. She says, “It is OK to make these sounds in your head. Like a football player. But a dancer must make it look effortless, light and lovely. That is the magic trick. That is the illusion.”

Back in British Lit, I sit beneath overhead fluorescent lighting and in my head I roar like a football player when the reflective glare flickers on our huge table around the shadows of my classmates’ moving bodies. I jot down my professor’s lecture notes. I roar against the pain of looking near (at my notebook) then far (at the chalkboard), near (at Bleak House) then far (at another student speaking). This is the magic trick, the illusion. That it doesn’t hurt like hell, that it isn’t nauseating, to just sit in class.

+

My instructor gives me a poster to take home. It reads: “Show up. Even when you don’t feel like showing up.”

I show up.

Because I have a secret goal—to be en pointe by the time I earn my PhD. I tell no one. I think, maybe, some things you keep to yourself, at least for a little while. For safekeeping.

Even when I don’t feel like showing up.

+

After my injury, I developed the habit of lighting a candle before sitting down to write. At the end of every session, I blow it out and bow my head.

At the end of every ballet class, we perform the ritual of the reverence. “Reverence usually includes bows, curtsies, and ports de bras, and is a way of celebrating ballet’s traditions of elegance and respect.”

+

What am I doing here and why?

Old answer: There is no Plan B.

New answer: I am here because I am a writer, and I show up to my classes even when I don’t feel like it. I commit myself to this fully, and I will not quit. For the act of reading and writing, like ballet, “is not just about who we are but who we can become.”

+