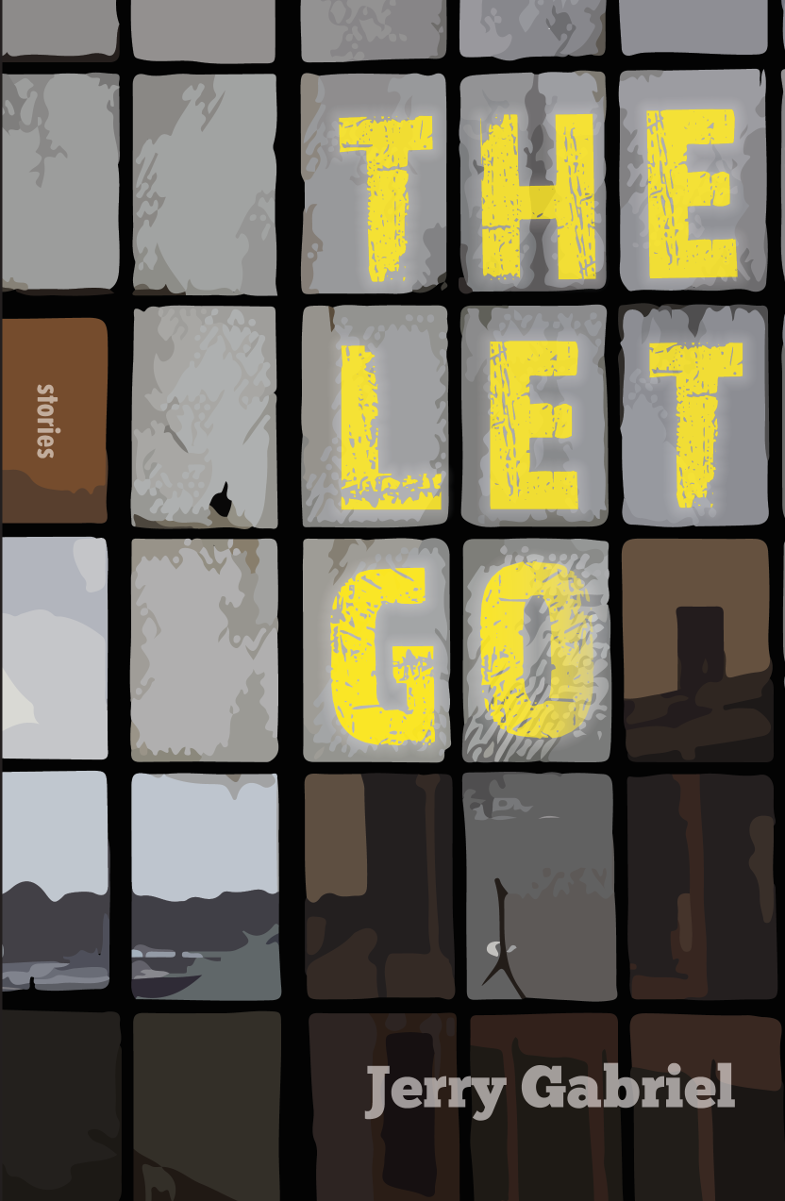

Queens Ferry Press, 2015

Jerry Gabriel’s debut collection, the Mary McCarthy prize-winning Drowned Boy, compiled a set of linked stories that worked magnificently as stand-alone pieces, but taken together as a whole, the collection read like a novel. In Gabriel’s second collection, The Let Go, the seven stories each read as something close to condensed novels, with perceptive character observations and meticulous plot developments. Gabriel never shies away from allowing his stories to go further, stretching to as long as forty-some pages. Despite a few instances of Gabriel perhaps leaning too heavily on these novelistic tendencies, The Let Go yields several stories that confirm Gabriel’s mastery of the long short story form.

The collection begins with a piece showcasing Gabriel’s ability to handle multiple narrative arcs. “The Visitors” is as much thirteen-year-old Camille’s story as it is her father’s, a story that bubbles with intrigue and mystery as Camille comes to understand the questionable virtues of a father whose poaching is far more innocuous than his other activities. Camille’s father is harboring fugitives, an act of rebellion against the government he blames for his brother’s death. The decision wreaks havoc between Camille’s parents. Camille never seems to identify much with her mother; instead, she’s content to follow along with her father’s deeds. What little she knows of her father’s background doesn’t dissuade her from idolizing him, as seen when he arrives one afternoon to pick up Camille from school:

At moments like this, when he was on display in front of her classmates, she knew that her shaggy, underemployed father was supposed to be an embarrassment, but she felt no such thing. Quite the opposite; she felt a kind of pity for other children who had to go home to a different, lesser father each night.

This admiration grows from a gradual understanding of her father and his motivations for committing treason. At the end of the near forty-page story, Camille and her father go in search of traps after departing with their most recent fugitive. In the cold Ohio weather, risking hypothermia, Camille is forced to shed clothing in front of her father:

Soon she was naked from the waist down and her father from the waist up. She was glad for the darkness, because though their relationship was extraordinary for a father and daughter, she had begun to feel the inevitable awkwardness about her ascension into womanhood. She knew that his would eventually alter things.

In order to save Camille, her father surrenders to a group of hunters whose land they’ve trespassed on. As the story concludes, Camille and her father are taken to a house to await the authorities, and Camille aligns herself again with her father, displaying the same rebelliousness as her father. Gabriel suggests Camille may see her role as daughter shift as she grows older, but her role as dissenter will continue to thrive. The character development throughout “The Visitors” is exhibited mostly by Camille but is inspired by her father. Gabriel takes on a lot with “The Visitors,” particularly in terms of character, and the results are flawless.

Gabriel exhibits something more peculiar in “Above the Factory,” which begins with a young couple moving to Ohio and taking up residence in a small community far from the busy city. Nicholas and Sharon Dawson buy quickly, neglecting to note the many downsides of the house, the most notable being a factory that comprises the basement. Neither the couple nor the realtor have any insight into this quirk, and despite the oddity of such a set-up, the Dawsons become accustomed to the people coming and going from their basement.

But this peculiarity can’t sustain the story forever, and midway through “Above the Factory,” Gabriel shifts his focus completely, turning to one of Nicholas’ co-workers, Roger, who doubts Nicholas’s happiness. The shift takes a moment to get used to, as the reader is thrust into Roger’s perspective, but ultimately it feels like a chapter break, and soon the reader is brought back to Nicholas and Sharon, only this time it’s through Roger’s eyes:

The best way Roger could think about Dawson, about his fascination, was as some awful urge—like the desire to binge eat that some people had. Or, if he were being honest with himself, it was probably more like a sexual desire. He felt a kinship with the furtive movie stars who got caught with some tart in their arms at an hourly motel. Nothing, he realized, is ever so gratifying as the thing you know you shouldn’t do but do anyway. That’s what this thing felt like.

Upon a trip to the Dawson’s house, Roger believes he sees a well-adjusted and content couple, a striking contrast to Roger’s life. In another seeming chapter break, Gabriel turns back to Nicholas and Sharon, who appear to have been shaken by Roger’s visit, and in the midst of a late-night swimming expedition, both of them conclude that their lives could, in fact, be more satisfying. The allure of a house with a factory isn’t so wonderful after all, and Gabriel ends the story with a fitting impression from Nicholas: “It was strange what happened to you in life…. People always said life was strange—there were even songs about it—but it wasn’t until that moment that he quite understood that idea.” Given the length of the story and how long the reader has spent with these characters, his contemplation seems to bear greater significance. “Above the Factory” feels like a compressed novel, and comparable to something many times its length.

Occasionally Gabriel seems too at ease with the long form, and rather than paring back, he allows a few pieces to become overextended. In the appropriately titled “Long Story, No Map,” Gabriel follows a nineteen-year-old who drifts around the campus of Ohio State and occasionally sleeps with a grad student. In between, the boy strikes up a friendship with his landlord, an older Korean, who eventually serves as some kind of mentor. While whatever resolution the story achieves is befitting the set-up, one might feel as though the story asks the reader to follow several loose ends. In such cases, Gabriel may have been determined to bring too much to the page.

The Let Go displays Gabriel’s penchant for writing long and allows him to exhibit a great deal of range, particularly in terms of character development. Aside from a few instances where readers may find a story meandering rather than moving ahead, Gabriel has amassed a fine collection on par with his debut.

+++

+