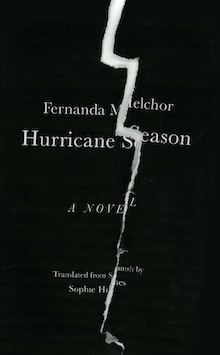

New Directions, 2020

The statistics are horrifying: worldwide, one in three women experience gender-based violence during their lifetimes; 58% of the 87,000 women murdered around the world in 2017 were killed by intimate partners or family members; in the United States alone, at least twenty-six transgender people were killed in 2019, of which 91% were black women. There is data available for everything — you can even look up how many women were stabbed to death versus shot — and so, in some ways, we know more than we ever did about the violence happening in our streets and behind closed doors. Yet unless we seek out the details of individual cases, the people behind the numbers are erased, reduced to figures in a spreadsheet.

Fernanda Melchor’s novel Hurricane Season is, in part, an exercise in rehumanizing the victims behind the numbers. In it, she creates a vivid portrait of the ways the intersection of different forms of violence — economic, environmental, obstetric, religious, and, above all, gendered — creates a storm system, trapping communities in its throes.

The book opens with a troop of boys, armed with rocks and slingshots, playing war in the brush leading down to the irrigation canal. It’s a game, and yet they’re scared, though even at this young age, they know better than to admit it. The stench reaches them first, then the horrible sight:

[…] the ringleader pointed to the edge of the cattle track, and all five of them, crawling along the dry grass, all five of them packed together in a single body, all five of them surrounded by blow flies, finally recognized what was peeping out from the yellow foam on the water’s surface: the rotten face of a corpse floating among the rushes and the plastic bags swept in from the road on the breeze, the dark mask seething under a myriad of black snakes, smiling.

It’s the Witch whose corpse smiles at the boys’ horror, and the mystery of her murder — and of who she really was — drives this roman noir. Composed of eight chapters, each with a singular focus, if not perspective, the novel is a quilt of voices of the community’s disenfranchised. They are the women who covered their faces on their visits to the Witch to “let it all out, the pain and sadness that fluttered hopelessly in their throat”. They are the sex-workers, the addicts, the gay men, the neglected girls forced into adulthood too soon. In recounting what each knows about the Witch’s life and death, the characters reveal their own dual roles as both victims and victimizers in a wider system of violence.

These voices are what make Hurricane Season a remarkable work. Represented in long, breathless sentences and chapters composed of a single paragraph, they are the speeches and tirades of the cantina, the jailhouse, the tienda where the women gather to buy eggs and gossip. Melchor deftly pivots between registers and tones as she renders the orality of each character’s speech, even switching mid-sentence to another person or institution’s perspective without ever interrupting the story’s momentum.

One striking example of this (and of Sophie Hughes’ translation skills) occurs in the fourth chapter, which focuses on Munra. For most of the chapter, the reader hears about Munra’s experiences from a close third person narration representing the man’s own voice. However, toward the chapter’s end, his narrative is spliced with its judicial translation, providing the reader the only indication that Munra was detained in connection with the murder:

Munra looked at the fuel gauge and thought that the most sensible thing would be to drive back to La Matosa and ask Doña Concha to put a litre of aguardiente on his tab and drink the whole thing in bed while he waited for Chabela to get home, and drink until he passed out or died, whichever happened first, and just then his telephone buzzed again and, once again, it was the kid, now telling him that he’d got hold of some cash, that he’d spot Munra’s petrol if he did him this one solid of taking him to a job, by which the witness understood that his stepson had required the services of taking him to a specified location where he could obtain the money to continue drinking […]

In her use of a multitude of voices, Melchor’s writing echoes Rulfo’s Pedro Páramo and Bolaño’s 2666 in fiction, and Poniatowska’s La noche de Tlatelolco (published in English as Massacre in Mexico) in nonfiction. Like these works, Hurricane Season strives to create a portrait of a place and time while rejecting the notion of a single story. The novel forefronts the impossibility of ever adequately representing the truth of even a single murder, when the violence that produced it is fractal, branching out in all directions.

Melchor is also a journalist who has written on violence in marginalized places like the fictional La Matosa of her novel, and Hurricane Season is loosely inspired by a real murder. Yet she chose to tell this story through fiction, which makes it all the more striking that by the novel’s end, so much remains unsolved. A bit more than half-way through the book, the reader knows who murdered the Witch and why, yet the more the reader learns about this particular murder, the more they understand that this crime is far from extraordinary in a town plagued by sexual and gender-based violence.

Once understood as a quotidian event, the Witch’s murder takes on another significance. The concrete motives that drove the murderers are insubstantial, insufficient to explain what in La Matosa generates the psychological and social circumstances that give rise to such acts of violence. There are clues, of course: the presence of drug traffickers, corrupt law enforcement, capitalism’s greed. Yet Melchor’s work reveals all of these to be symptoms as much as causes of a wider system. The novel offers the reader an uncomfortable ending, one that recognizes the impossibility of resolution in a situation where the root causes remain unresolved. In so doing, Hurricane Season reinforces the question at the heart of the novel and lingering behind every set of crime statistics: if violence is a system, and as much a part of our daily existence as the weather, what can we do to change our climate?

+

+

+