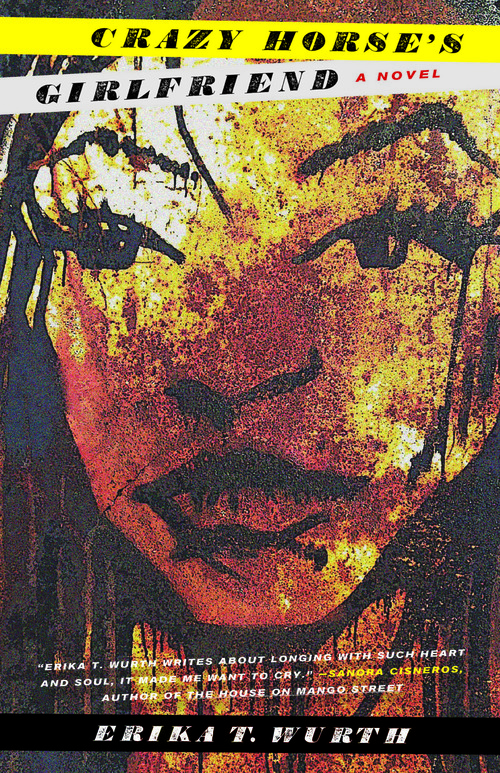

Curbside Splendor, 2014

Erika T. Wurth’s debut novel sets a stark, provoking tone with the first sentence: “I was sitting around in the basement of yet another fucking drug fuck, when I decided to get nervous.” This is the reader’s introduction to Margaritte, a surly, hardened sixteen-year-old drug dealer. Along with her cousin Jake, Margaritte is desperately trying to save enough drug money to finance her escape from an abusive father, depressing family, and dilapidated, reservation-border town of Idaho Springs, Colorado. She dreams about running off to Paris with Mike, a new and exotically Californian high-schooler whose own fantasies of fleeing his life mirror Margaritte’s. But when Margaritte turns up pregnant, she’s left with long odds against ever breaking the pattern of unhappiness she’s surrounded by.

Crazy Horse’s Girlfriend fits in well with Curbside Splendor’s fearless and gritty aesthete, and Wurth herself isn’t skimping on the grime. Within the first 25 pages Margaritte is stabbed by a meth-head and beaten by her alcoholic father. Readers who stop at this point may worry the other 262 pages are more of the same depressing material. And while Wurth’s book is anything but sunny, the hopeless events of the novel are buoyed by fascinating and complex personalities. Wurth works hard to remove her characters from Native American stereotypes and statistics, even as Margaritte fears falling into them. Will is an especially interesting character, a gay loafer who takes advantage of his cousin Megan—Margaritte’s friend and single mother—but who also connects with Margaritte unlike any other resident of the crumbling town. On the same page Will is described as both “coming close to crack whore-dom” and “the only person in my [Margaritte’s] life who would go and see arty films with me.” Will becomes everything Margaritte fears, a person intelligent enough but too afraid to leave Idaho Springs. He’s hated and admired, toying with the reader’s emotions throughout the narrative.

Margaritte’s mother is another such character, appearing strong in one sentence and pathetic in the next. She tries to protect Margaritte but is constantly distracted by taking care of her twin toddlers and tip-toeing around Margaritte’s volatile father, with whom Margaritte’s mother is locked in an endless, exhausting battle. This is indicative of the world Wurth has crafted in Idaho Springs, a dark, muddy place with an invisible suction that Margaritte struggles against on every page. It’s a relatable dilemma, the thirst to get as far away from one’s depressing hometown. Margaritte’s mother is the embodiment of that fear, a hard woman fringing on the edges, barely holding together the universe around her:

“Mom, you always, always say that.”

“Say what?”

“That he’s doing better.”

“I used to love him, you know,” she said. She was looking at the pile of papers in front of her.

“Do you still?”

“Sometimes. Or . . . maybe I love the memory of what he was. Or maybe . . . I still love him when he’s not . . . you know he does love you, in his way.”

“I know.”

A strong comparison between Margaritte and her mother—compounded by Margaritte’s pregnancy—lasts throughout the novel. She faces a choice between aborting her child to run away or having her baby and losing her chance to get out of the sad cycle that’s claimed her mother.

At a glance, Wurth’s writing reads as overly simplistic. The sentences occasionally run together with a repetitive quality: “My grades were shitty, which was sad considering that the goddamn place graduated illiterates. But I just hated school. I read Stephen King under my desk in Math. I was always getting caught.” While this simplistic style is a bit grating at first, a reader quickly acclimates once realizing these staccato sentences emerge not from Wurth’s lack of ability but from a perspective tightly aligned with Margaritte’s voice. (To understand Wurth’s range, check out this brilliant short piece from Split Lip Magazine) Wurth’s technique opens as the book progresses, eventually leading to chapters in which the writing is just as dirty, complex, and beautiful as the characters:

The walls were covered in old, yellowing wallpaper, wallpaper that was peeling off in large sheets, exposing rotting walls underneath sticky with beige glue. Kids had spray painted everywhere; gang shit, random shit, Betty loves Bob kind of shit. . . . It was as if Idaho Springs had some sort of collective poetry, and it was all over the walls of this abandoned complex.

Crazy Horse’s Girlfriend is an intimate look at Margaritte’s bleak world of burnouts, drug addicts, and dreamers. Her desperation to get away pulses on every page, and the reader can’t help rooting for the characters of Idaho Springs to find the happiness they so fiercely desire. If you’re searching for emotional impacts delivered by a poignant, sardonic voice, pick up Erika T. Wurth’s new work.

+++

+