Our Translation Notes series invites literary translators to describe the process of bringing a recent book into English. In this installment, Adrian West writes about translating Alma Venus by Pere Gimferrer (Antilever Press).

+

Upon learning he had won the Rómulo Gallego prize for his novel The Savage Detectives, Roberto Bolaño phoned Pere Gimferrer, “who is a great poet and who also knows everything and has read everything,” in the novelist’s words, to pump him for details about the Venezuelan writer for whom the award had been named. It is true that Gimferrer is daunting in the same way as Robert Burton or Edmund Wilson, and his often bracing, frequently frustrating omniscience reduces the translator’s role to what is at best a stimulating blend of research and conjecture and at worst that of a spy in an adventure film with a bad foreign accent, praying that no one will blow his cover.

Upon learning he had won the Rómulo Gallego prize for his novel The Savage Detectives, Roberto Bolaño phoned Pere Gimferrer, “who is a great poet and who also knows everything and has read everything,” in the novelist’s words, to pump him for details about the Venezuelan writer for whom the award had been named. It is true that Gimferrer is daunting in the same way as Robert Burton or Edmund Wilson, and his often bracing, frequently frustrating omniscience reduces the translator’s role to what is at best a stimulating blend of research and conjecture and at worst that of a spy in an adventure film with a bad foreign accent, praying that no one will blow his cover.

I came to translate Gimferrer because my former French professor, a Cuban who has lived more than forty years in the United States without taking citizenship because, he says, he always imagined Castro would die and he could go back and become a senator, mentioned to me a Catalan novel that reminded him of Proust. Fortunately the novel actually existed, unlike the equally intriguing Baudelaire à l’ordinateur, an alleged study of the metrical characteristics of that poet’s unusual lexicon of which I have never found a single trace. The novel was called Fortuny, as in the famous designer and lighting engineer of whom I knew nothing at the time. It recounts the lives of two generations of the Fortuny and Madrazo families and their artistic acquaintances, who ranged from Wagner to Henry James to Chaplin and Eleanor Druse, and takes place mainly in Paris and Venice.

Being naïve enough to imagine that something so lushly written would be recognized for its virtues no sooner than it had appeared in English, I translated a ten-page section for Asymptote in January of 2013. It was difficult because, like his touchstone author Góngora, Gimferrer’s descriptions may linger on the naked sensory properties of an object for pages before the reader knows precisely what that object is: this is especially so in the descriptions of paintings that open the book. Moreover, the measured nature of the author’s long phrases and the precision of his vocabulary leave little room for stopgaps or approximation.

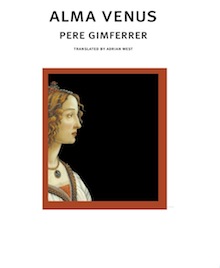

Some months later, I received a message from Antilever Press, who had become acquainted with Gimferrer’s name because Harold Bloom confers upon his “Selected Poems” the honor of inclusion in the Western Canon — perplexingly, since I am unaware of such a book’s existence. After some discussion, we decided to publish Alma Venus, the long poem cycle that had just been released in Spain that year.

Alma Venus is a love poem, written in Castilian rather than Catalan because, according to the author, a love poem must be written in the language in which the romance was conducted. We opted for a bilingual edition, which helped to alleviate my greatest fear — that of accidentally omitting a line. Before I began translating full-time, I imagined the job was an artistic one, and while in many cases this is true, I feel just as often like a forensic investigator charged with finding evidence of my own crimes: as when, through absentmindedness, I translated “mannerism” as “magnetism,” or failed to see an obvious allusion to Rilke. I was fortunate to be given several opportunities to weed these things out, and the version we have ended up with appears to be a clean one; but the experience gives one to think of the malevolent savor with which many critics will pounce upon errors which in most cases are probably less the fault translators’ unscrupulousness or incompetence than of publishers’ desire to forego printing galleys and the rush to get books to press.

Every target language encourages its own bad habits. Because I translate from German as well as Romance languages, I try to give attention to finding the right register, the right balance between the formal and the demotic: the Romance languages often tempt one to a tone that’s too turgid, too laden with syllables, while German compels one to file down away too much. “Lachhaft” suggests “laughable,” but often “ludicrous” or “preposterous” is better. Gimferrer, though, is a special case: his polysyllabic strophes are a product neither of pretension nor of the natural relative languor of Latinate verse in comparison with English; they rather represent a wide-ranging sophistication the failure to preserve which would render translation futile. Sometimes he can’t be matched at the level of the individual word: for example, he employs a number of synonyms for daybreak that often lack satisfying English equivalents. When this occurs, the best solution has at times been to save things for later. Thus I have preserved the rarefied English word “comulgated” in the line “Give me your comulgated clarities” not because it corresponded in register with the line in question — in Spanish the verb comulgar is more common, and taking the line on its own, “Give me your clarities in communion” might have been more faithful — but rather out of a concern for a global representation of the erudition and nuance evident in the work as a whole.

I think I have more or less managed this. Gimferrer has said himself in a recent interview, “It is not necessary that the reader know what I am talking about, or that he be acquainted with the cultural references, but only that he sense a verbal reality that previously did not exist, that he feel the images and sounds.” It is unrealistic to expect that a general reader, particularly one from the Anglophone world, where Gimferrer’s web of references, both European in general and Iberian in particular, are largely unfamiliar, to grasp every allusion in Alma Venus; but I believe and hope that the beauty, the passion for light and shadow, for the carnal, and for art, shine through in a poem like the following:

Lady of the almond eyes,

Ladyship of the county of the sea,

Lady with the crosier of snow:

Time has stamped a medallion

With your face and mine: we are nothing

Without this coursing of flares,

So that we will be able to live on

(“To do is to live on,” said Aleixandre)

And be thunder flash, lightning bolt, taper:

The thunder in the distance will tell us the voices

As in Eliot’s verse, a tolling

Sounds afar after the final bell call,

Tells the hour the clock does not tell,

That of Dreyer’s Gertrud, pealing

Of the hour that is no hour, atemporal.

The fine mesh of your blond dreams,

The lion’s den of intensity

Have buckled toward your eyes,

Fiery in their resplendent venery.

In the weightless winds, the night

Acknowledges the sieve of the spark:

It is in your eyes.

Give me in these hands

The red tree of youth.

+

Adrian West is a writer and translator whose work has appeared in numerous publications, such as McSweeney’s, The Brooklyn Rail, Words Without Borders, and Asymptote, where he is also a contributing editor. He currently lives between Europe and the United States with the cinema critic Beatriz Leal Riesco.