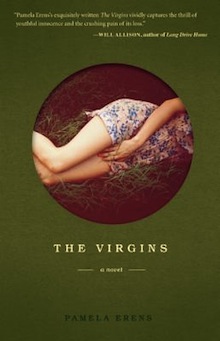

Our Research Notes series invites authors to describe their research for a recent book, with “research” defined as broadly as they like. This week, Pamela Erens writes about The Virgins (Tin House).

+

Based on the research I did for my second novel, The Virgins, here is a book I might have written:

Based on the research I did for my second novel, The Virgins, here is a book I might have written:

(Feminist mystery with Mexican Communist elements):

A lost Diego Rivera mural is discovered behind a wall in a Planned Parenthood clinic in New Haven, Connecticut. The staff is tempted to sell the exceedingly valuable mural to offset drastic cuts in federal funding for family planning, but moral rectitude dictates that instead the clinic director take a trip to Mexico to discover the provenance of the work, which turns out to have been stolen by the former owner of a Newark, New Jersey department store. The plot involves twisted revelations about the leader of a Communist worker’s party in Mexico City. The guilty are punished, the mural is donated to the Diego Rivera Foundation, Congress increases Planned Parenthood funding.

That one doesn’t grab you? Okay, how about this?

(Domestic drama with political themes):

A prominent theater director’s young son is diagnosed with a neurological disorder. The director’s wife is convinced the disorder was caused by the family’s proximity to an active nuclear power plant. She becomes the public face of a wildly successful, if unscientific, effort to link nukes and autism. The director believes his wife is nuts, and the marriage is strained to the breaking point. Meanwhile, the director is getting ready to mount a stage version of Theodor Dreiser’s An American Tragedy, and, highly attracted to his leading lady, decides to re-enact the climactic scene in which the main character engineers the drowning death of his fiancee so he can be free to pursue another woman….

No? Good news. The Virgins — the novel I really did write — is about three teenagers at an East Coast boarding school in the late 1970s. It’s about navigating early sexual experiences; teens dealing with racial differences; storytelling. But the process of composition took me through some interesting byways, not all of them relevant in the end. I did research into auditory hallucinations, schizophrenia, and the history of Concord, New Hampshire. I read an oral biography of the theater producer Joseph Papp, watched a movie on the Weather Underground, spent time at a Planned Parenthood clinic, and drove to Seabrook, New Hampshire, to visit a nuclear power plant. I investigated Mexico City outdoor markets, got my library to obtain a lavish book of reproductions of murals by Diego Rivera, and read the very long Theodore Dreiser novel An American Tragedy.

Other research did make its way into my book — minimally. I reread Wuthering Heights to get a few lines of conversation between my female protagonist, Aviva Rossner, and one of her friends. My visit to the Seabrook power plant informed a scene that eventually got cut, but I kept one line in which the plant is visible from a beach where two girls are spending a spring afternoon. I listened to music by Devo — one my male protagonists is a Devo fan — and Googled the history of department stores in Newark, New Jersey. The best investment-to-return ratio was a visit to Phillips Exeter Academy, the boarding school I attended as a teenager, to take notes and photographs. I find it very difficult to invent large and complex physical spaces from scratch, so it was helpful to use Exeter’s grid for the fictional boarding school in my story.

I love doing research, because it allows me to read about fascinating subjects and count this as working rather than wasting time. But I also hate doing research, because any “writing” hour that I’m not actually putting words down on the page leaves me a bit empty and guilty and scared. I have the nagging fear that if I ever stop writing, even for a few days, I will never write again. I can never quite see how to cut back on the time I spend doing research, and yet it always seems to me that I spend too much. The problem, of course, is that while one is researching one never knows which parts are going to be useful and which will not. I’m not sorry I read An American Tragedy — Dreiser is canonical, and I was previously unfamiliar with him — but there went a week in did I which nothing else, writing-wise. And nobody’s going to give me back the money I spent on a hotel and gas and meals so that I could visit the Seabrook power plant. That one line in my novel cost nearly two hundred dollars.

I am a slow writer, and I didn’t publish my first novel until the age of forty-four. The Virgins is coming out the month I turn fifty. I no longer have as much of that feeling of it’ll-take-as-long-as-it-takes as I used to. I’d like to produce a few more books before I kick the bucket, and my four-year average is beginning to feel a little self-indulgent. So, as I work on my third novel, I’ve been promising myself that I’ll do less research this time. Why, then, am I reading my way through a stack of nine books on Haiti? Will I ever use this material? Or by the time I’m done, will my protagonist live in Sweden? I have no idea.

I can’t even claim that the information I stuff myself with has broadened me and made me a better-informed person. The fact is I generally forget everything I’ve learned not long after I’ve either used or discarded it. For my first novel, The Understory, I did an enormous amount of research into plant ecosystems and taxonomies. For a few months I could have told you some things about viburnum and witch hazel and the difference between dicots and monocots, but it’s all gone out of my head now.

In truth, though, I doubt I’ll have any success trying to curb my research impulse. Once in a while it does bring me a gem that I couldn’t have found in a less wasteful, more deliberate manner. Besides, research, for me, may be a psychological necessity, a way of maintaining emotional homeostasis. Writing fiction is challenging and uncertain, and involves delving into uncomfortable (if imaginary) feelings and experiences. It’s understandable that at times — or often — we writers feel dread and resistance. When that resistance becomes too strong, research can be a way to continue the work while relaxing the tension, giving permission for a bit of extracurricular play. A research day may not be a day my word count increases, but it’s one in which I manage to maintain my interest in and enthusiasm about my book-in-progress rather than retreating to my bed filled with self-loathing and doubt. Sometimes, in the writing life, the ability to hang on to the momentum is the most important thing of all.

+++