What books and/or authors have had the most influence on your writing?

Some of the most obvious influences on Kino are probably writers like Thomas Pynchon, Alan Moore, Ernest Hemingway, Thomas Mann, my teachers Frederick Barthelme and Mary Robison, my wife Marcy Dermansky — but I’ve also drawn a lot of inspiration from the movies: Orson Welles, Francis Ford Coppola, David Lynch, Roman Polanski, Nicolas Roeg, George Lucas, Alfred Hitchcock, Fritz Lang, and many more. Plus the non-fiction, which I’ve listed before in a Research Notes post at Necessary Fiction.

Some of the most obvious influences on Kino are probably writers like Thomas Pynchon, Alan Moore, Ernest Hemingway, Thomas Mann, my teachers Frederick Barthelme and Mary Robison, my wife Marcy Dermansky — but I’ve also drawn a lot of inspiration from the movies: Orson Welles, Francis Ford Coppola, David Lynch, Roman Polanski, Nicolas Roeg, George Lucas, Alfred Hitchcock, Fritz Lang, and many more. Plus the non-fiction, which I’ve listed before in a Research Notes post at Necessary Fiction.

How do you decide when a piece you’ve written is “finished” enough to publish?

When I can read it a few times in different formats without changing anything. That’s a brief, rewarding moment — before someone else starts telling me what I need to do before it can be published.

What would you consider to be a productive day of work, and do you have a writing routine?

When I’m working on a book, I like to write every single day to keep my head in it, with some breaks at key points, like a finished draft. Other than that, I make time any which way I can. It’s great to have hours and hours of undisturbed writing time, but sometimes you can do more in one really good hour than an entire blah day.

What part of your writing process do you most enjoy?

When it’s just me and the page. Doesn’t matter if it’s first ideas popping, the actual writing, or revision. As long as there’s some kind of progress, I love it, and when it’s going well, it’s the best. I’d rather be doing nothing else. But then there’s the other part, where you have to hock it and pimp it and get it out into the world. You want to be good at that, you have to be good at that, but it’s not writing. That’s being a writer, and I could do without it.

You were an associate editor for fiction at the Mississippi Review Web, and you taught English and Creative Writing at USM and Manhattan’s Laboratory Institute of Merchandising. How has your experience as an editor and teacher shaped your work?

I think it’s given me a little distance to evaluate my own work, to look at it as an editor or teacher might and see what works and what doesn’t. You can read it as you would a submission and you wonder, would this make it past me? Would I keep reading if it wasn’t mine? It’s a very useful thing to learn.

You founded one of the first German-language literary web magazines, Der Brennede Busch. What was your motivation behind this project?

This was in 1996, the time of screeching modems and Mondo 2000 and this whole utopian cyber thing, the idea that the web would change everything. I was in grad school, we’d just put the Mississippi Review online, and I figured, hey, this is possible, so why not let’s try it? It really wasn’t any more complicated than that. I taught myself HTML, asked a friend to design a cover image, and there it was. I remember late one night that summer, I was sitting in a house in the Irish countryside, uploading an essay someone had emailed me from Tokyo onto a server in Mississippi for an audience in Germany, and it felt like the future. That was the first time I tasted that kind of global potential. Der Brennende Busch had a good run.

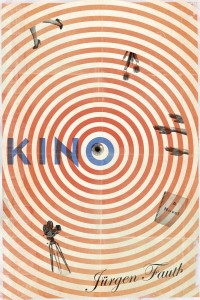

Your new novel, Kino, takes interest in the role that the cinema plays in audiences’ lives as well as the political power it holds. How did this subject intrigue or inspire you to write about it?

Right after the Aurora shooting this summer, there was a flurry of articles online, mainly by film critics, assuring everyone that the Batman movie playing in that theater couldn’t possibly have anything to do with the killer’s motives. And I thought that was remarkable. Not because I believe that the opposite is the case, exactly — I don’t expect we’ll ever understand what drove him to do it — but I thought it was odd how eager people were to outright deny the possibility that the movie had anything to do with it. If we knew that for sure, wouldn’t that mean that the movies were essentially powerless, that they could never have any influence on the world whatsoever?

I’m not suggesting any kind of one-on-one cause and effect between violence in the movies and in the world or anything like that. But I believe that in some way, everything influences everything else, and the movies are overwhelming, intensely exciting guided trips built for hundreds of millions of dollars by a global industry that’s very much preoccupied with results. I think it’s absurd to suggest that they have no repercussions in the real world.

So my book takes the opposite idea and runs with it. It’s concerned with questions of propaganda and mind-control, and there’s a suggestion that the movies have a kind of supernatural power to reshape reality. Which isn’t as nutty as it may sound when you consider that real-world mobsters took their mannerisms from The Godfather and that the countdown was invented as a dramatic device by Fritz Lang. I mean, we all have these complex and very vivid shared memories that come from the movies, and they constantly reappear in our conversations and our dreams. I’m fascinated by that back and forth between our consciousness and what’s on the screen, between the world and the movies. As a film professor says in the book, “just because you understand the technology doesn’t mean you grasp the essential mystery of it.”

__Kino_ is set in Nazi Germany. What is it about this time period and place that moved you to write about it?_

In Germany, there’s a law called the “Bundesvergangenheitsbewältigungsschutzgesetz” that requires that 5% of any novel has to be set during the Third Reich — or at least it feels that way sometimes. Most of the historical parts of Kino actually take place during the Weimar Republic, the time between the wars when Berlin was home to all kinds of upheaval as well as an incredible flowering of arts and culture. The movies of the time especially intrigued me, all those huge Ufa productions, and researching the book was a lot of fun. Those years really were the proverbial dance on the volcano, and I was drawn to this in-between moment when anything seems possible. I wanted to find out how my characters would react when it all reached this terribly abrupt and cruel end.

What else are you working on, and where can readers go to find more of your work?

I’m currently working on clients’ books for our editing business, MJedit, and I’ve begun translating Kino into German. There are a few excerpts and shorter pieces listed on my Fictionaut page.

Finally, what advice would you give yourself when you first started writing?

“Write more. Don’t worry if it’s good or bad, just spend more time doing it.” Steve Barthelme once told me that you have to write at least 1,000 bad pages before you can even begin to turn out anything worthwhile. At the time I thought that was preposterous. Now I suspect it’s a low estimate.

+++